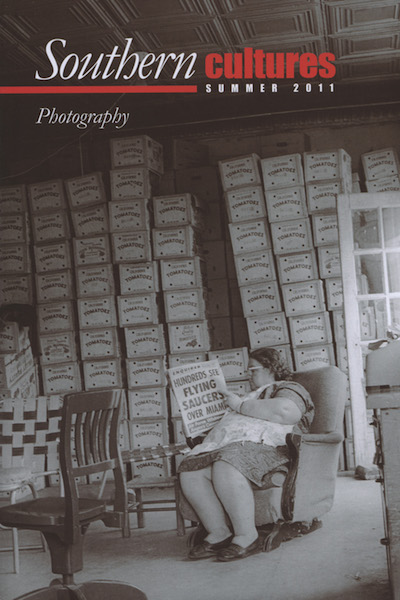

This article first appeared in the Photography Issue (Vol. 17, No. 2: Summer 2011).

“It is in fact hard to get the camera to tell the truth; yet it can be made to, in many ways and on many levels. Some of the best photographs we are ever likely to see are innocent domestic snapshots . . . .” —James Agee (1946)“One of the most envied accompaniments of high birth in the past is becoming almost universal. Almost everyone nowadays is possessed of family portraits . . . As in the case of jewels, there is something fictitious about the store which is set by them. Nevertheless the fascination of such heirlooms is eternal.” —The Living Age (1913)1

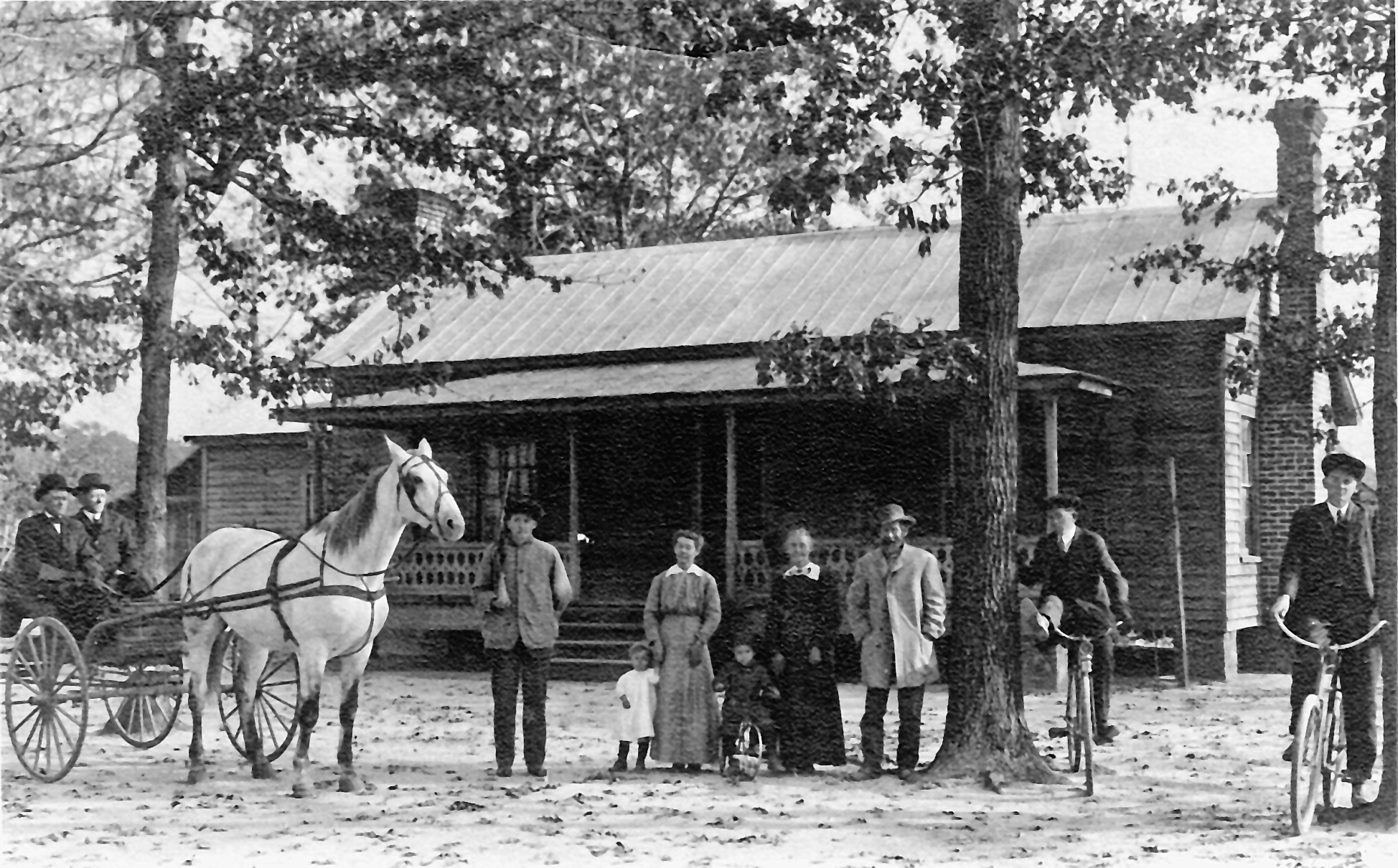

The family photographs presented here come from a collection my great-aunt kept at the family home-place in the Rosebud community of Wilson County, North Carolina. Stowed away in shoeboxes marked “The Good Ol’ Days,” these photographs chronicle life in a small corner of the coastal plain from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first century. The pictures portray the cycles and rhythms of rural life and the people who shaped the region’s unique landscape and language, architecture and culture. The families seen in the photographs—Matthews, Taylor, Pender, Varnell, Barnes, Flowers—intermarried and created a community sustained by agriculture, barbecues, hunting, fishing, and visits on the porch.

Family, private, personal, domestic photographs—however you choose to name them, they often seem unremarkable to those unfamiliar with the people and places depicted in the pictures. They do not aspire to art. If they are propaganda, it is of the familial sort. Domestic photographs can seem commonplace and pedestrian unless you care to take an empathetic, imaginative leap into the lives of the people in the images or, especially, if you have a personal connection to them. Then they seem alive and of inestimable value. They are what you would grab first in a fire.

Then they seem alive and of inestimable value. They are what you would grab first in a fire.

In recent years, I made regular visits to my great-aunt’s house on my way to and from school in central Virginia. She and my grandfather were born in this house, which my great-grandfather built around 1900. Though many of the trees that provided shade in earlier years have succumbed to storms or pruning, the home remains a quintessential eastern North Carolina farmhouse: a white, one-story, symmetrical square plan with a low, hipped roof and wraparound porch. Each time I pulled in the long driveway toward the house, my great-aunt stood waiting by the door, ready to get right back on the road and “carry me” to Parker’s BBQ a few miles south for supper. When we returned home we would sit on the porch, weather permitting, and after a while move into the living room to watch sports, game shows, or sitcoms from the 1960s.

As evening turned into night, and after three or four bottles of Coke, which my great-aunt kept well stocked for my visits, I always turned my attention to the drawer in the living room that served as a portal to my family’s past. Inside was an ancient family Bible, containing birth records from the 1760s, my great-great- grandfather’s Confederate veteran ribbons, scattered pages from the Primitive Baptist newspaper, scraps of paper with song lyrics composed for a funeral (“The hand of death alone can blot / Those images from my heart / Forget, forsake me if you will / You never shall be forgot”), a summons from 1911 to testify in court on behalf of the plaintiff, along with many other items used to mark favorite passages of Scripture. Next to the Bible sat the shoeboxes of photographs. They ranged from glass-plate studio portraits from the late nineteenth century to Polaroid Instamatics of more recent vintage. The bulk of the photographs, however, originated from the 1920s through the 1940s and documented daily life on the farm, recreational activities, and interactions with family and friends.

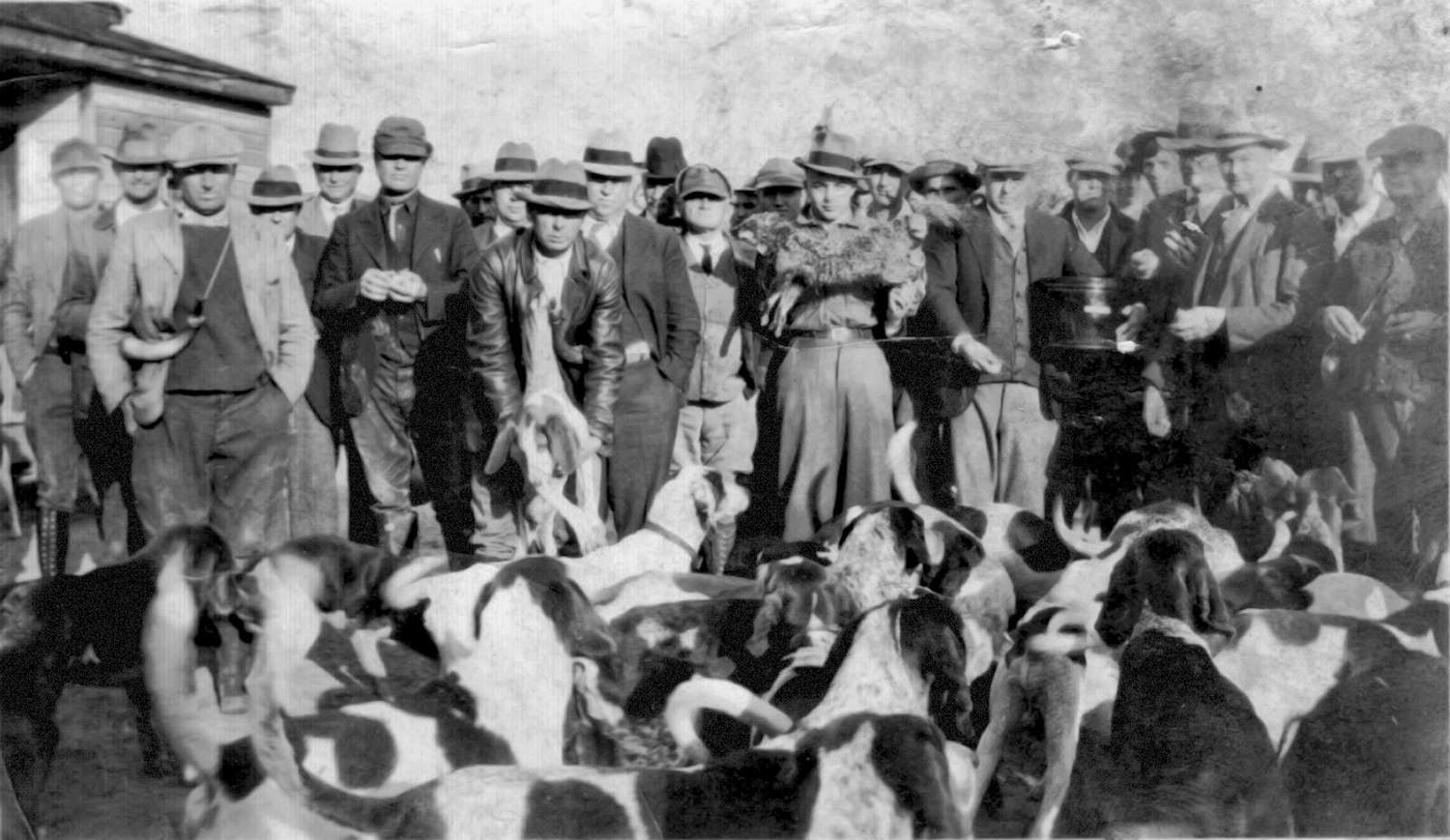

Opening the shoeboxes, I became an armchair archaeologist, carefully sifting through the artifacts in an attempt to reconstruct a society that looked at once familiar and foreign. I would spend the rest of the night peering into the faces of relatives known and unknown, here and gone: my great-grandfather—he holds the lapels of his leather jacket, standing with pride next to a pair of slaughtered hogs hanging from hooks, while two African American tenants each pull a hog from its sides. My grandfather—newly enlisted in the Navy before the outbreak of World War II, where mythic places like Europe and the Pacific yet await him—stands in his uniform with his mother and sister before the family home. My great-grandmother—wearing an unusual and faint smile for the camera—sits in a rocking chair on the porch, her apron on but enjoying a rare rest. My great-grandfather again: he stands buffer-like between white and black men after a hog killing, exuding power and control. The face of an unknown, bespectacled African American woman peers just above the bottom frame; she stands before a tobacco barn with a wistful expression. And what seems like a scene from England: foxhunters—all wearing fedoras or ivy caps, most adorned with neckties, their hounds’ eyes still trained on the fox.

Opening the shoeboxes, I became an armchair archaeologist, carefully sifting through the artifacts in an attempt to reconstruct a society that looked at once familiar and foreign.

My great-aunt always patiently answered my questions about the people in the pictures and provided stories to accompany them when she could. For instance: the black bear on a chain that keeps showing up?

Papa bought him from a man named Weaver, who found him down toward the coast in Hyde County. He brought him home and named him Ted. I was always so scared of him. Ted used to ride in the passenger seat of Papa’s convertible when he drove into town. He’d leash him up and take him to the warehouses for tobacco auctions, too. One day Ted bit him. Papa took a 2 × 4 and killed him with one swing. When he came inside, he said to Mama, “Sal”—he called her Sal—“I had to kill that bear.”

During the past few years, death has visited my father’s side of the family with unwelcome regularity: a great-uncle, a grandmother, a cousin. My father died suddenly in the summer of 2008. Two months later my great-aunt passed away at eighty-seven. Her brother, my grandfather, followed one year later at the age of ninety-one. My grandfather and great-aunt were the last surviving siblings among eight brothers and sisters who grew up on the family farm in Rosebud. With their passing came the loss of the home-place where my great-aunt lived her entire life. Soon after their deaths, the family also decided to sell off their adjoining land—acres reserved for soybeans, timber, tobacco, cotton, and corn. The sale marked the end of the family’s connection to the land that began in the late eighteenth century.

Amid the loss of life, land, and links to place, the family photographs I pored over during my visits with my great-aunt have become the torchbearers of memory. They conjure the immanence of loved ones, like my great-aunt as a teenager who wears saddle shoes while tying tobacco in the shade on some oppressive August day, they evoke Sunday dinners spent inside listening to stories of fishing in the Alligator River near the coast, they summon the howls of the baying hounds and the odors of alcohol, tobacco, and sweat of the hunters. These visual records, once prompts for the eldest generation’s stories and memories, now help preserve and pass on those oral traditions to succeeding generations, as land used to be. The photographs and their stories are woven into the fabric of individual and family identity and create a sense of belonging and tradition for future generations who never knew their forbears or stepped foot on ancestral land.

Family photographs, of course, tend to whittle history down to an idealized, mythic past easily sentimentalized and misremembered. Since the 1970s, a growing body of historical and cultural studies on family photographs has tried to uncover their meanings and messages. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes about how family photographs could function as umbilical cords that reconnected him to a lost mother, while more recent assessments have used theoretical insights like “hegemonic familial ideology” and “monolithic familial gaze” to make sense of what such photographs mean. Who, though, gets to decide what a photograph, created by and intended for family and friends, ultimately means? Even within families, the meanings of photographs vary widely depending on who is looking and the unique level of familiarity the viewer has with the people and places within the frame. When family photographs leave the home for the archive, the museum, or the journal, do the photographs’ private or familial meanings matter anymore, or do we defer to the revelatory, though occasionally arcane, theories of academics?2

Who, though, gets to decide what a photograph, created by and intended for family and friends, ultimately means?

I can only say what these photographs have meant to me, what they have told me about my family’s life during the early and middle twentieth century in a particular place in the coastal plain of eastern North Carolina. As a historian, I also recognize their historical value as depictions of rural life in the South during first half of the twentieth century. They reveal the centrality of agriculture to life, the nature of race relations and gender roles on the farm, the significance of recreation, particularly hunting, and how all of these activities and relationships create structures of power as well as a sense of community, belonging, and place. These photographs, and the many others like them sitting in drawers, boxes, and photo albums throughout the country, can provide visual clues to support or challenge oral histories and census data about life on a southern farm in the early and middle twentieth century.

When looking at these family photographs, I find myself comparing them to more notable and public documentary images like those produced by Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers during the Great Depression and New Deal. The chronology of most of the photographs presented here overlaps with the work of FSA photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Jack Delano, Marion Post-Wolcott, and Walker Evans, who roamed rural America documenting people, places, and vernacular architecture. My family photographs, however, have no identifiable creator. The backs may contain the names of the individuals in the picture, but the photographer is a phantom. Content, not style, takes precedence in family photographs. Style and the cult of the artist, on the other hand, remain in the foreground of traditional documentary photography, as viewed by critics and popular audiences or even spoken about by their creators. We learn more about Walker Evans and his photographic style by looking at his Depression- era photographs from Hale County, Alabama, than we do about the tenant families he photographed and later featured in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his famous collaboration with the writer James Agee. Evans aspired to use a camera as Gustave Flaubert used a pen, hoping to mimic the French novelist’s dispassionate realism, his “objectivity” and “non-appearance” as an author. The illusion of “non-appearance” has now become one of the visible markers of Evans’s style. In contrast, the family photographs presented here make no pretensions toward art, documentary realism, or public propaganda. Though they are priceless to my family and me, I feel fairly certain that no one will ever pay $4,000 for a photograph of my great-grandmother, as collectors have done in the past for “an Allie Mae” [Burroughs], one of the Hale County farm women Evans photographed in 1936.3

The photographer in these family photographs has only a spectral presence, but he or she is nevertheless an “insider,” a member of the family or community being documented. Traditional documentary photographers, no matter how tactful and self-effacing, still confront ethical dilemmas about prying into the lives of other people. They must navigate the vast chasms of class, cultural power, and sometimes race. These tensions and divides, even when they remain unspoken or unnoticed, shape the relationship between photographer and subject, and color the style and content of the photograph. Had Walker Evans simply dropped off a couple of cameras for the tenant families to use to document their lives as they pleased, would we know more about the predicaments of their “human divinity,” which the writer James Agee stated as one of the purposes of his collaboration with Evans that summer?4 Would we learn more about America during the 1930s and 1940s by looking through the often-haphazard archives of family photographs found in homes across the country than by studying the 170,000 images FSA photographers produced during the same period?

A photograph’s enduring value, of course, does not come from its ability to convey things as they are or were. The past seen within the frame is always a mirage. We take—and return to—photographs for another kind of truth, one that is hardly historical or universal but based on a personal, emotional, and aesthetic experience. Our visceral response to a photograph can come from its compositional beauty or the sublimity of the scene. In the case of snapshot images, like most family photographs, that emotional response comes from a recognition or feeling of connection to the people seen in the picture. When I look at my family’s photographs I tie together the stories I have heard about the people in the pictures with whatever hints of personality, character, and circumstance I can glean from the image. Through imagination, I transform family members I was too young to know, or who now only exist in my memory, from flat figures in a photograph to people I can still see, hear, and touch. I see in my great-grandmother, as she stands before her house or finds a moment of relaxation on the porch, a face that betrays strong emotion—a fortitude born of a deep Baptist faith, of years of unending work on the farm, of sadness from losing children at birth and from influenza, of heartbreak because of a husband renowned for drinking and carousing, of worry for her children whether they were hunting possum at night or invading a place called Inchon in Korea. I hear her toward the end of her life, now under the care of a loving daughter, son-in-law, and sons, as she rocks in her chair in the living room of the family home-place, dipping snuff and spitting into a metal coffee container while watching Perry Mason. She lived to be ninety-one and never left North Carolina.

We take—and return to—photographs for another kind of truth, one that is hardly historical or universal but based on a personal, emotional, and aesthetic experience.

These imaginative acts are aided by holding the photograph, touching its creases, tears, and dog-eared corners, smelling the scents it has collected over eighty years sitting in shoeboxes or quilt-covered trunks. Holding, touching, and smelling a family photograph, one in which everyone seen is now gone, gives it an almost sacred quality, like a relic. It is a tangible memorial that keeps the dead alive, one that can be passed around the living room after dinner or during family reunions, something that coaxes the stories and remembrances that are, in turn, passed on to new generations. The photographs maintain family ties and identity even in the face of inevitable death.

Today’s digital cameras and cell phones can capture limitless moments in a family’s life, but these images often are forgotten on hard drives and susceptible in an instant to the fate of “data loss.” As family photographs lose their tactility, as they become stored megabytes and gigabytes, like so many other parts of one’s life, do they also lose their individuality, their ability to function as revered heirlooms? The sheer number of photographs someone can take with one digital camera also changes the way a person approaches snapping the shutter. When confined to 12, 24, or 36 exposures, a family photographer, perhaps of limited means, makes sure each picture matters. It took my family over a century to amass a collection of some three hundred photographs. Today, families can take hundreds of pictures in a month or a week. Does the sheer number of family photographs now at our disposal on cameras, phones, and computers—and their accompanying tools of image manipulation—also erase their relic-like eminence? Certainly people lamented the loss of a photograph’s distinguished aura with the advent of the portable Kodak camera back in the 1880s, which made photography accessible to the masses. Future generations will undoubtedly find new ways to venerate family photographs. The fascination, it seems, is eternal.5

My father and I rarely communicated through email, preferring the occasional phone conversation when time permitted. One of the last of the three email exchanges I had with him before he died came about because I had sent him some family photographs I scanned onto my computer after visiting my great-aunt in North Carolina. He was a kind and reflective person but hardly the most expressive, particularly when it involved personal matters, which explains in part why we never kept up email correspondence. The photographs, however, summoned emotions and memories, however modest, which broke through the reserve:

It’s funny how looking at photos can cause you to remember things like smell and touch. Some of the photos remind me of cold, clear mornings at Granny Matthews’s as we were getting ready to walk through some of the fields for god only knows what reason when I was about six years old. I can still remember these enormous breakfasts being served—probably ate some of the relatives of those hogs in the pictures!

It is not the accuracy of memory but the act of remembering that matters most to me when thinking about my father’s, or anyone else’s, response to family photographs. It testifies to a feeling of belonging and reveals a wellspring of emotion that says less about the past and more about a shared humanity.

Scott Matthews is an assistant professor of history at Florida State College in Jacksonville where he grew up. He received his PhD in History from the University of Virginia and is completing a book on the cultural impact of documentary work in the American South during the twentieth century.NOTES

- Helen Levitt, A Way of Seeing (Durham: Duke University Press, 1989), vii; “Old Photographs,” The Living Age, vol. 279 (1913): 689.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill & Wang, 1982); Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997); Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981).

- Joseph Anthony Ward, American Silences: The Realism of James Agee, Walker Evans, and Edward Hopper (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2010), 145; Howell Raines, “Let Us Now Revisit Famous Folk,” New York Times, May 25, 1980, SM8.

- James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families (New York: Houghton Miffin Harcourt, 2001), x.

- The are numerous examinations of photography, the digital age, post-modernism, and post- post-modernism that deal with these issues at a deeper, more theoretical level. Walter Benjamin prefigured these debates back in the 1930s, particularly his now widely known and referenced ideas about how the rise of mechanical reproduction, including photography, erased the “aura” of individual works of art. See Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken, 1969); W. J. T. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992); Fred Ritchin, After Photography (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010).