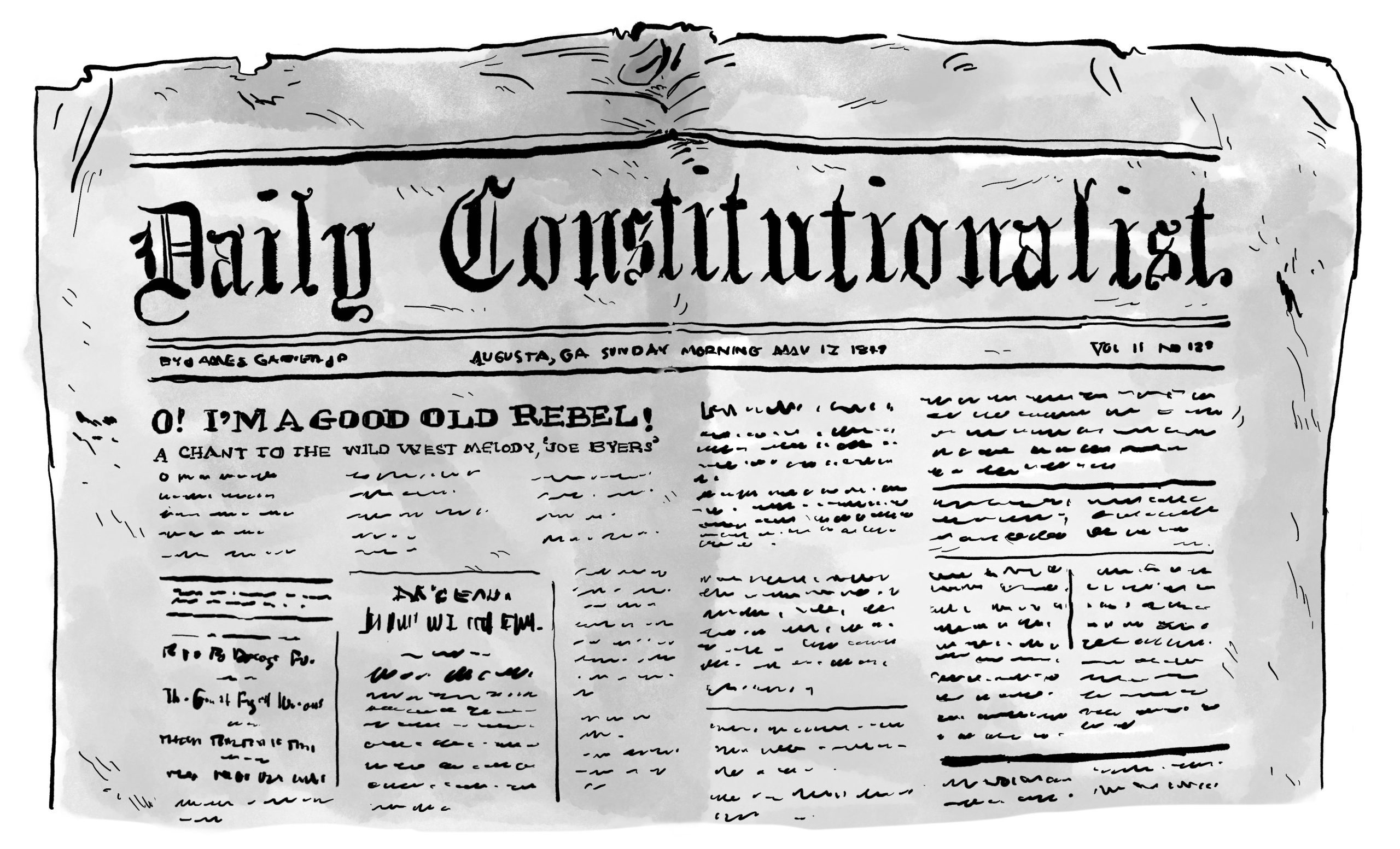

On July 4, 1867, Augusta, Georgia’s newspaper, the Daily Constitutionalist, published the words to a new song that seemed to reflect the bitterness felt by many white southerners following the Confederate defeat. The paper printed the song’s title as “O! I’m a Good Old Rebel” above a spiteful dedication to Thaddeus Stevens, the abolitionist congressman from Pennsylvania. It also provided the instructive subtitle “A Chant to the Wild Western Melody ‘Joe Bowers,’” letting readers know they should sing the lyrics to the minor-keyed folk tune to give “Good Old Rebel” a mixture of melancholy and menace. The paper did not include an author attribution, but given the first-person perspective, the unpolished vernacular, and the tone, it appeared that a recalcitrant Confederate veteran had penned the lyrics. This anonymous author seemed to cling to his identity as an unrepentant traitor who twists failed rebellion into victimhood. He begins, “O I’m a good old Rebel, / Now that’s just what I am; / For this ‘Fair Land of Freedom’ / I do not care at all,” with the italicized “at all” censoring an obviously rhyming but omitted “damn.”1

The next four verses took the denunciations of the United States even further. “Good Old Rebel” inventories all of the nation’s founding documents and symbols that he hates, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the US flag, as well as the Freedmen’s Bureau, the agency created in 1865 to implement the plans of Reconstruction and help formerly enslaved African Americans transition to liberty. The author casts himself as a victim of postwar oppression while claiming he would like to “kill some mo’” US soldiers. In the final verse, he pledges to never accept Reconstruction, claiming, “And I don’t want no pardon, / For what I was and am; / I won’t be reconstructed. / And I don’t care a cent” [another omitted “damn”].2

Flash forward to the twenty-first century. Dozens of YouTube videos of “Good Old Rebel” have logged hundreds of thousands of plays for professional and amateur renditions of the song. Viewers from all over the world often leave pro-Confederate, pro-secession comments. These YouTube users, veiled in the anonymity that social media affords, feel a connection to “Good Old Rebel” and the imagined South that it summons, a South of continual rebellion against an allegedly oppressive federal government. They hear a kinship born of antigovernment resentment, authenticated with grammatical errors and familiar themes of political resistance. The song creates a space and a soundtrack for sympathetic listeners to perform what they imagine as their truest selves without the propriety of normative US patriotism. Hearing their views echoed in such an old song injects a bit of nineteenth-century popular culture into the political framework of the modern radical Right and affirms their politics in the here and now. It validates their feelings.3

The irony is that “Good Old Rebel” is not real—not exactly. “Good Old Rebel” started as a joke. Innes Randolph, a journalist, poet, and descendant of a prominent Virginia family, wrote those words, born partly out of his experiences as a Confederate soldier and partly as a means to lampoon poorly educated, working-class white southerners. Yet Randolph’s verses leaked into circulation for decades after the war as an anonymous and, some believed, authentic folk song. This process of dissemination largely erased Randolph’s attempt at humor and projected his personal rancor onto poor white southerners, many of whom had been reluctant to fight for the slaveholder’s secession during the war.4

The fact that “Good Old Rebel” blurred the line between satire and sincerity so well meant that generations of audiences found malleability within the song’s meaning. Some have taken the lyrics to heart. Some hear the song as a curiosity that seems too over-the-top to be serious. Still others find an attraction to the song’s nihilism wrapped in romantic imaginings of the Confederate foot soldier. The life of “Good Old Rebel” as a misinterpreted joke exposes how satire, however unintentionally, can skew the author’s original purpose. In this case, Randolph’s satirical poke at lower-class whites has helped neo-Confederates and their sympathizers envision themselves as victims. But “Good Old Rebel” has attracted audiences and performers from across a range of political backgrounds whenever they need to represent the unreconstructed white South with a tune. An excavation of this song’s origins and influences reveals how it found adoption as folklore, made its way into midcentury popular culture, and continues to spread through social media.

Historians have long understood how Lost Cause proponents romanticized the Confederacy to enforce white political power after the Civil War. But “Good Old Rebel” holds no pretense of honoring martial valor like a Confederate statute or sanitizing the slaveholding South with a tune like “Dixie.” Instead, it represents three crucial components of the white supremacist South and its contribution to the culture of the modern radical Right. First, “Good Old Rebel” encourages listeners to imagine revenge against the government and its expansion of civil rights for African Americans. Second, with an accent coded as uneducated, “Good Old Rebel” helps listeners cast those political feelings onto white southerners, sometimes referred to as “rednecks” or “hillbillies,” who often act as pop culture’s punch lines. Third, that shifting boundary between the song as a joke and the song as a threat allows “Good Old Rebel” to align with the modern-day “alt-right” communities that thrive online and traffic in ironic humor and plausible deniability to further their political agendas. “Good Old Rebel” offers a lesson in the way music can propel ideologies of antigovernment violence and further the imagined South shaped by white supremacy.5

The Satirical Origins of

“Good Old Rebel”

This song’s journey starts with James Innes Randolph Jr. and the following poem that he wrote sometime around 1867.

Oh, I’m a good old Rebel,

Now that’s just what I am;

For this “fair Land of Freedom”

I do not care a dam.

I’m glad I fit against it—

I only wish we’d won,

And I don’t want no pardon

For anything I done.I hates the Constitution,

This great Republic, too;

I hates the Freedmen’s Buro,

In uniforms of blue.

I hates the nasty eagle,

With all his brag and fuss;

The lyin’, thievin’ Yankees,

I hates’em wuss and wuss.I hate the Yankee Nation

And everything they do;

I hate the Declaration

Of Independence, too.

I hates the glorious Union,

‘Tis dripping with our blood;

I hates the striped banner—

I fit it all I could.I followed old Mars’ Robert

For four year, near about,

Got wounded in three places,

And starved at Pint Lookout.

I cotch the roomatism

A-campin’ in the snow,

But I killed a chance of Yankees—

I’d like to kill some mo’.Three hundred thousand Yankees

Is stiff in Southern dust;

We got three hundred thousand

Before they conquered us.

They died of Southern fever

And Southern steel and shot;

I wish it was three millions

Instead of what we got.I can’t take up my musket

And fight’em now no more,

But I ain’t agoin’ to love’em,

Now that is sartin sure.

And I don’t want no pardon

For what I was and am;

I won’t be reconstructed,

And I don’t care a dam.6

Born in 1837, Randolph traced his lineage back to William Randolph, the patriarch of one of the “First Families of Virginia” whose other descendants included John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson. Although Randolph’s immediate family enslaved at least three people at one time, they were not wealthy planters and often experienced severe financial hardships. Despite those struggles, Randolph excelled in writing, sculpting, and playing the violoncello and completed his education at the New York State and National Law School. During the late 1850s, he practiced law in Washington, DC, where his father made a modest living as a congressional clerk. In May 1861, Randolph enlisted as a Second Lieutenant, Engineers, and drew maps for the Confederate Army. He served on campaigns in North Carolina, as well as in the Shenandoah Valley on General Richard S. Ewell’s staff, and spent the latter years of the war stationed in Richmond.7

Randolph earned a reputation in the Confederate capital city as an artistic and quick-witted member of a salon for Confederate intelligentsia called the Mosaic Club. Although he had joined the war effort eagerly, he also wrote poems poking fun at Confederate blunders, suggesting that his willingness to fight for secession did not limit his ability to laugh at the military’s missteps and defeats. The writer Thomas Cooper de Leon, a fellow Mosaic Club member, described how “no pen, or no brush, in all the South limned with bolder stroke the follies, or the foibles, of his own, than did that of Innes Randolph.” De Leon also noted how Randolph satirized the poor white southerners’ reaction to the Confederate loss, remembering, “It was at the Mosaic that Innes Randolph first sang his now famous ‘Good Old Rebel’ song; and there his marvelous quickness was Aaron’s rod to swallow all the rest.”8

Of course, Randolph did experience a semblance of the bitterness expressed in “Good Old Rebel.” His father died during the war years. He felt his wife was in danger from US forces, and he suffered the usual soldierly miseries that accompany poor diet and little rest. Some of Randolph’s other poems reinforce the resentment he felt because of Confederate defeat and the alleged injustices of Reconstruction. In 1867, he penned a poem for the dedication of the John Marshall statue in Richmond that complained to the inanimate chief justice how he would not recognize Virginia in its then current status as an occupied military district, complete with a pun about martial law.9

Military service also forced Randolph into contact with white southerners whom he considered beneath him, and he resented how these wartime hardships stymied his artistic pursuits. In January 1863, while stationed in North Carolina, Randolph wrote to his mother about his experiences in the field. According to her, Randolph “was quite unwell and as blue as indigo. He is in charge of the Tar [R]iver defenses. He appears to think that he has reached the climax of N.C. stupidity. He is in the family of a Mr. Peebles whom he says is a good sort of a stupid fellow and that his wife is a match for him. He has no books, no society, no any thing but ignorance.” Stuck with the white South’s unlearned citizens, Randolph wanted desperately to return to the company of literature, drama, and his fellow educated rebels.10

However, Randolph’s artistic success did not flourish after the war. He died in 1887, having spent most of his postwar career as a journalist for the Baltimore American. In 1898, his son tried to rescue his father’s literary legacy by publishing a book of Randolph’s verse and included “Good Old Rebel.” The younger Randolph also clarified how his father felt about the Confederate defeat. He believed that, due to military duties and postwar economic hardships, his father “was not permitted to turn his attention to music, painting, sculpture or literature, in any one of which, with proper training, he might have accomplished great things.” “[As] with so many of his brothers of the South,” Randolph’s son wrote of life during Reconstruction, “[My father] confronted not the questions of artistic or literary development, but the more immediate problem of bread and butter.”11

drain Randolph of his artistic prowess, he had given those years in service to an experimental nation whose average white citizens, in his estimation, might be as ignorant as the Peebles family. “Good Old Rebel” also failed to achieve Randolph’s literary goal, as it escaped the circles of his educated peers. By the late nineteenth century, the song belonged to and appeared to speak for the very people it mocked. While Randolph certainly harbored hostility over the failed Confederate rebellion, “Good Old Rebel” projected the most violent impulses of that bitterness onto white working-class southerners.

The Music and Folklore of “Good Old Rebel”

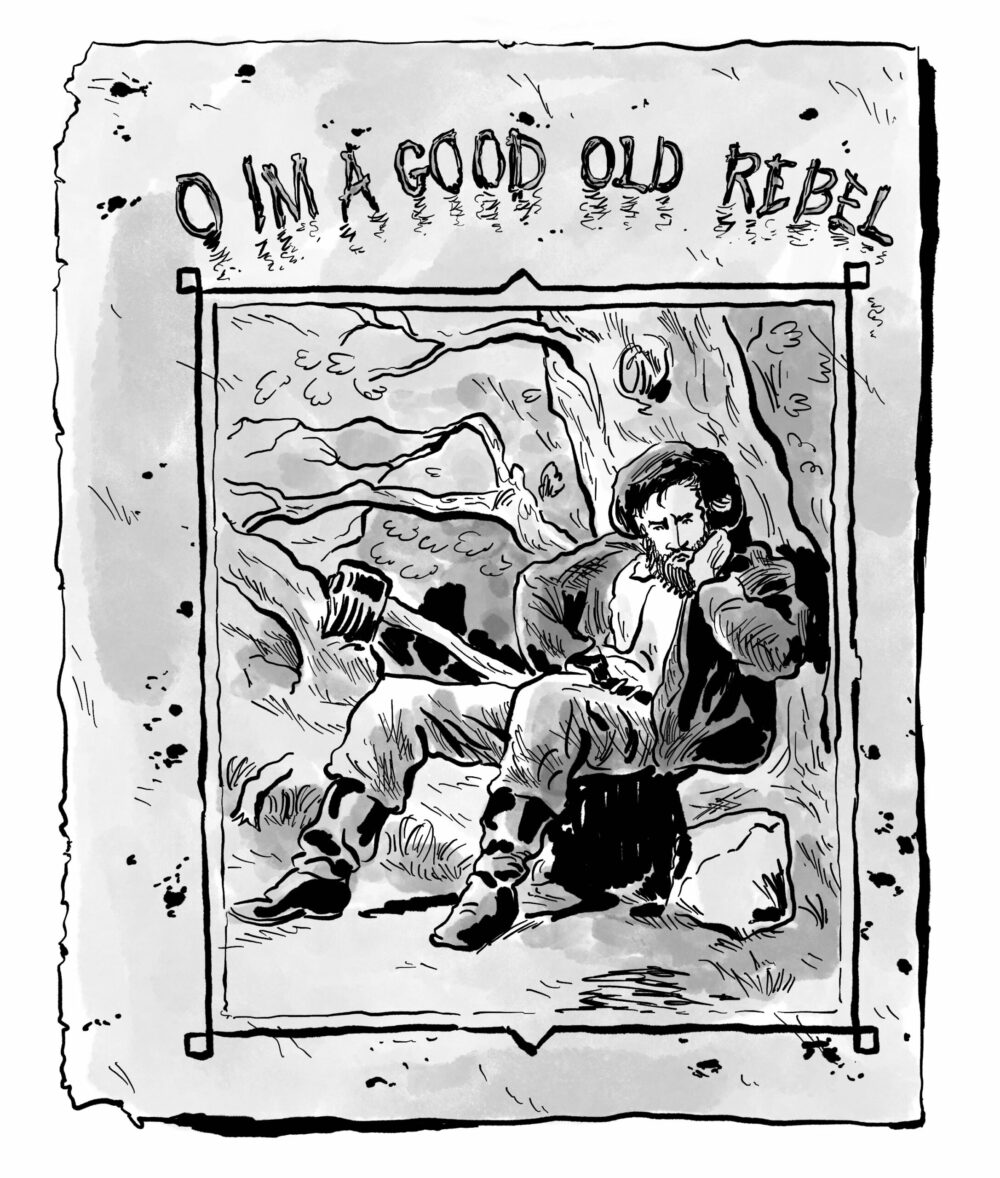

The cover art for the only known piece of sheet music of “Good Old Rebel” leaned into interpretations of the song’s apparent sincerity, although it also leaves room for the original humor. This undated publication features a bearded white man in civilian clothes, his only visible possessions fitting into a tattered haversack next to him on the ground. His face, resting on his hand in contemplation, reflects the lyrical dissatisfaction and anger. Any buyer of this music likely presumed that this character was the narrator of the song, an embittered veteran of the Civil War, possibly on his way home from some point of surrender. And yet, if they were inclined to see the rebel as a sore loser, then the illustration might well read as a comic figure, ridiculous in his stubbornness like a cartoonish hillbilly stereotype.12

Other publications used illustrations of the rebel to balance the vengeful with the absurd. In 1890, “Good Old Rebel” appeared in W. L. Fagan’s collection Southern War Songs: Camp-fire, Patriotic, and Sentimental. Fagan wrote that the pieces in his volume were “part of the history of the Lost Cause” and “necessary to the impartial historian in forming a correct estimate of the animus of the Southern people.” There, among the predictable songs like “Dixie,” was “Good Old Rebel,” credited to the initials J. R. T. without any mention of Randolph. Fagan also included a drawing that could be interpreted as a Black man between the verses with the caption “I’m a Good Old Rebel” printed underneath.13

Readers may have believed that a Black man sang “I hates the Freedmen’s Buro” without irony. Confederate reunions often featured former enslaved men who posed as Black Confederate veterans. As Kevin M. Levin has written, Lost Cause adherents created narratives about enslaved people who remained faithful to their white enslavers in a bid to sanitize the evils of slavery, expunge the institution’s centrality to secession, and establish “a model of deference to a new racial order” of Jim Crow segregation. At the same time, readers may have also taken the illustration as some new iteration of the joke, imagining these words from the mouth of a man whom the rebel would like to see returned to slavery. The possibility of multiple interpretations suggests that white readers could either laugh at the song’s narrator or seethe along with its malice, depending on one’s position.14

“Good Old Rebel” attracted more than Lost Cause promoters. In the early twentieth century, the song’s reputation as a genuine folk song garnered the attention of academics and journalists interested in documenting the nation’s vernacular culture. John Lomax believed the “Good Old Rebel” ruse and included the song as an anonymous creation in his collection Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads. This version, published in 1910, dropped the reference to the Freedmen’s Bureau and added a verse about seeking postwar refuge in Mexico. Lomax failed to include where he found the song, but the rebel’s wish to “start for Mexico” reflected the fact that some former Confederates did flee to Mexico after their defeat to wait out the retribution for their rebellion.15

Four years after Lomax published his work, Collier’s magazine began running open calls for information about the nation’s folk songs. According to the April 4, 1914 edition, the magazine received a “flood of replies to an editorial request for … what we supposed was a real American ballad in which an unreconstructed rebel declares … he’d like to take his musket an’ go an’ fight some mo.’” Collier’s noted with a tone of disappointment that, based on the responses received from the request, the magazine determined the song was not a traditional ballad but, in fact, Innes Randolph’s creation.16

Letters from people claiming to know the song came from New Mexico, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, New York, Michigan, Illinois, Missouri, and California. A respondent from Washington, DC, informed readers that he had recited the poem many times at both US and Confederate veterans’ meetings and learned the words from a Confederate veteran in the 1880s. He described the song as “a glimpse into the heart of the genuine old unrepentant, unreconstructed rebel … of whom there are only a few more left.” Collier’s chimed in with its belief that the song was “a very concrete reminder of passions long dead.” The writer likely meant that the “passions” of secession no longer threatened the stability of the union. But with Black Americans then experiencing the peak of the twentieth-century lynching epidemic and the formation of the Second Ku Klux Klan only a year away from this publication, Collier’s mistakenly conflated the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction with the end of resentment and violence. For the magazine, sectional reconciliation among white northerners and southerners equaled peace for everyone and erased the Black Americans who had earned their freedom by fighting the slaveholder’s regime.17

Academics, including the Agrarian Donald Davidson, continued to include “Good Old Rebel” in their work throughout the 1930s and 1940s as a half-comedic, half-serious poem of the Lost Cause. According to Alan Lomax, President Franklin Roosevelt liked the song enough to use it as a tool to win over the white southern politicians who made up the conservative wing of the Democratic coalition. The president had an accordionist play the song at the White House and also requested local musicians perform the song whenever he met with southern Democratic leaders at his retreat in Warm Springs, Georgia, during legislative battles for the New Deal. It seems that the political architect of an expanded federal state used “Good Old Rebel” as a kind of cultural diplomacy to earn the confidence of skeptical southern politicians.18

Folklorists and singers documented and performed “Good Old Rebel” as the New Deal fascination with southern folk cultures bled into the folk revival. In 1942, a folklorist for the Library of Congress recorded Booth Campbell of Cane Hill, Arkansas, performing the first known audio recording of the song for the collection Folk Music of the United States: Anglo-American Songs and Ballads. Folk singer Hermes Nye recorded a major-keyed version of the song for Folkways Records in 1954, which appeared again in 1960 on folklorist Irwin Silber’s compilation of Civil War songs. By treating “Good Old Rebel” as a relic worth preserving, the folk revival inadvertently gave the song renewed relevance and exposure just as the Civil Rights Movement gained national political victories.19

The “Good Old Rebel” Meets Pop Culture

In 1957, the song made its cinematic debut with the release of Run of the Arrow. The film tells the story of an ex-Confederate named O’Meara, played by Rod Steiger, who fired the last shot at Appomattox and refuses defeat. Folk singer Frank Warner performs the song early in the film, setting the tone for O’Meara’s defiance. Rather than accept Confederate defeat, Steiger’s character goes West to live with the Sioux nation where he can avoid swearing allegiance to the Union. O’Meara eventually sees this move as a mistake, and he returns home to rejoin the nation he abandoned.20

As the battles over school integration raged in the late 1950s, it is possible that segregationists saw a fellow traveler in Steiger’s character and heard an attractive political stance in “Good Old Rebel.” Yet Samuel Fuller, the film’s director, intended the story as a critique of white southern bigotry and wanted to capture the similarities he saw in the anger over Confederate defeat and the modern Civil Rights Movement. As he told an interviewer in 1965, “They still fly the Confederate flag down there … And the feeling of hate, instead of decreasing has increased.” For Fuller, “Good Old Rebel” represented an authentic worldview of white southern racism persisting over the century that passed between the war and his filmmaking.21

“Good Old Rebel” has continued to spread through cinematic outlets over the past forty years. The song appeared again in 1980 in Walter Hill’s film The Long Riders, a reimagining of Jesse James’s gang who robbed banks and trains as retribution, in part, for the Confederate defeat. Ry Cooder produced the soundtrack, which included originals and period pieces. In 1991, country singer Hoyt Axton recorded Nye’s major-keyed version of the song for a music-focused spinoff of Ken Burns’s Civil War documentary series. These versions introduced “Good Old Rebel” to new generations of moviegoers and armchair historians, presenting it as a bigoted voice of the working-class white South in the process.22

Even artists with progressive political reputations have recorded versions of “Good Old Rebel.” In 2001, Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley of the Drive-By Truckers, who currently perform with a “Black Lives Matter” banner onstage, collaborated on a version with bluegrass musician Kirk Rundstrom and The Shiners, an alt-country band from Richmond, Virginia. Their rendition appeared on the soundtrack for an independent film called The Thrillbillys. This grindhouse-inspired film tells the story of revenge-seeking hillbillies who wage war against the modern-day “carpetbaggers” represented by a mega chain store that threatens to destroy local businesses and the protagonists’ moonshine operation. And in 2012, an interracial group called The South Memphis String Band, consisting of Luther Dickinson from the North Mississippi Allstars, Jimbo Mathus of Squirrel Nut Zippers fame, and Alvin Youngblood Hart, recorded an instrumental version of the song for their album Old Times There …23

One explanation for why these artists have covered “Good Old Rebel” lies in the ways that each of them has combined the libertarian rebellion and populism of rock ‘n’ roll with a defensiveness about white southern identity. Mathus released an album in 2011 entitled Confederate Buddha that features a Confederate battle flag necklace on its cover and songs about outlaws and cotton farming. In this sense, Mathus follows the lead of 1970s southern rockers like Lynyrd Skynyrd, whose members mixed Confederate flags and working-class machismo with countercultural cachet. Similarly, Charlie Daniels’s “The South’s Gonna Do It Again” (1974) and Hank Williams Jr.’s “If the South Woulda Won” (1988) conflated southern identity with Confederate rebellion in ways that echo “Good Old Rebel.”24

While the Drive-By Truckers steer clear of Confederate imagery, they have built a career documenting, critiquing, and sometimes romanticizing the economic and social hardships of the South’s white working class. Joining the musical tropes of “redneck” southern rock music with self-reflective deconstructions of that same redneck way of life, they have filled their songs with characters who often embrace nihilism and self-destruction as a means of release and escape. Yet even the Drive-By Truckers, whom critics recognize as one of the most thoughtful bands recording today, did not always navigate the waters of racial politics with the awareness that they now exhibit. Patterson Hood, one of the band’s principal songwriters, has discussed the regret he feels regarding the group’s name, as it plays into notions of Black-on-Black violence and the white privilege of consuming hip-hop without experiencing the realities that led to the genre’s creation. As for their participation in recording “Good Old Rebel,” it is possible that they heard an ancestor to one of their modern-day tales of fatalistic abandon, someone willing to burn it all down in the face of certain defeat. However, to hear personal freedom in the call for armed rebellion against the federal government is itself a privilege of whiteness. Converting Confederate secession into a personal secession requires an ahistorical perspective that only makes sense through the eyes of people who have not suffered under generations of systemic white supremacy.25

The theme of libertarian rebellion against all authority has helped “Good Old Rebel” find its largest audiences through the modern folk exchange of YouTube. The site hosts dozens of videos for the song, most of which include montages of historical images and white supremacist memes. The most recent comments on these videos reflect how deeply “Good Old Rebel” resonates with present-day neo-Confederate and radical right-wing movements. Samples include, “We’re two countries trapped in the same borders We will never have peace until we separate ourselves from the radicals,” “If the left removes the electoral college we’ll have another civil war,” and “Long live the SOUTH. We are going to rise. Keep a[n] eye on the horizon.”26

One YouTube user adapted the song as a Tea Party anthem during the Obama administration. The performer used the major-key melody of the song, retitled it “I’m a Good Ole’ American (Anti-Obama Song),” and rewrote the verses to denounce what he interpreted as a totalitarian Democratic administration. Much like “Good Old Rebel,” “Good Ole’ American” relishes the thought of fighting the federal government for what he views as an infringement on personal liberty and states’ rights. “Now I’m a good ole American / Now that’s just what I am / And for the liberal nation / I do not give a damn / Don’t want to rise against her / But I’ll gather up my guns / My freedom won’t be taken / I’ll fight’em til I’ve won.” The singer goes on to list the other entities he hates, such as welfare programs and Obama’s stimulus bill. Most of the comments support the song’s sentiments, connect the lyrics to Trump’s 2016 victory, and voice white supremacist attitudes toward Obama and his supposed infringement of individual liberties. For those on the radical Right, this is a freedom song, pointing toward a future unrestricted by governmental control. In this sense, “Good Old Rebel” accomplishes what the most effective political music can do. It distills complicated ideologies into rhyming verses, including antigovernment white identity politics.27

Given the song’s slipperiness between potentially misleading humor and sincerity, it makes sense that “Good Old Rebel” has found a home with the modern radical Right. Scholars have noted how the twenty-first-century alt-right relies on a combination of irony and purposefully shocking positions to deflect critics from its goals. For years, right-wing provocateurs like Gavin McInnes thrived on outrageous statements and actions that begged audiences to wonder if they were serious. McInnes, a self-proclaimed “Western chauvinist” who cofounded Vice media and founded the Proud Boys hate group, often deflects from his anti-Semitic, anti-Muslim, and homophobic remarks by insisting that critics just cannot take a joke. Likewise, the style guide for neo-Nazi website the Daily Stormer encourages its authors to keep their tone “light” because “most people are not comfortable with material that comes across as vitriolic, raging, non-ironic hatred. The unindoctrinated should not be able to tell if we are joking or not.”28

“Good Old Rebel” offers a nineteenth-century version of this discursive trick but deployed to further the antigovernment, white supremacist beliefs of the unreconstructed South. Like an ironic meme, the song’s success lies in the way it proclaims its hatred out in the open but delivers it in a tone or, more specifically, an accent that diffuses the seriousness of its message. Instead of spreading through internet media, it spread through newspapers, magazines, veterans’ reunions, and the pages of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century folk song collections. Similar to the messages pushed by alt-right activists who gathered at events like the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville and gather online still, the song encourages its receptive listeners to imagine themselves as defenders of an allegedly superior but vanishing culture. The white South, “Good Old Rebel” tells them, is under attack. The federal government has forced them, like the Confederates of the 1860s, into a subjugated existence. And as activists, local governments, and other institutions rightly remove Confederate memorials from the physical and cultural landscapes, “Good Old Rebel” may find even more listeners who long for the imaginary South of the Lost Cause and take up arms in its defense. Or, maybe this is all overblown. After all, this is just a song. A joke. Surely, no one hates the Constitution? No one really wants to refight the Civil War, right? Right?

This essay first appeared in the Imaginary South Issue (vol. 26, no. 4: Winter 2020).

Joseph M. Thompson is an assistant professor of history at Mississippi State University. His first book project, Cold War Country: Music Row, the Pentagon, and the Sound of American Patriotism (forthcoming, University of North Carolina Press), examines the economic and symbolic connections between the country music industry and the US Defense Department since World War II.NOTES

- Daily Constitutionalist, July 4, 1867, 4.

- Daily Constitutionalist, July 4, 1867, 4.

- Hoyt Axton, “OH I’M A GOOD OL REBEL – HOYT AXTON – YouTube,” Stanley 8244, October 22, 2013, YouTube video, 2:01, https://youtu.be/fT50xE1TMIo.

- Victoria E. Bynum, The Long Shadow of the Civil War: Southern Dissent and Its Legacies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980); Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003); Christian McWhirter, Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

- Innes Randolph, Poems, comp. Harold Randolph (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1898), 30–31, https://books.google.com/books/about/Poems.html?id=ydABAAAAYAAJ.

- Curtis Carroll Davis, “Elegant Old Rebel,” Virginia Cavalcade, Summer 1958, 43–47; Taylor Stoermer, “William Randolph,” Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, accessed September 14, 2020, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/william-randolph#footnote5_s5q9h9n; Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Schedule 2, Slave Population, Ward 3, District of Columbia, Washington; National Archives Microfilm Series M-432, Record Group 29, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Ancestry.com, accessed July 6, 2020; James Randolph to Peyton Randolph, November 21, 1853, series 1, Peyton Randolph Letters, 1853 (July–December), box 4, folder 4, John T. Harris Papers, 1771–1937, SC 0089, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University (hereafter Harris Papers).

- Davis, “Elegant Old Rebel,” 45; T. C. DeLeon, Four Years in Rebel Capitals: An Inside View of Life in the Southern Confederacy, from Birth to Death; From Original Notes Collated in the Years 1861–1865 (Mobile, AL: Gossip Printing, 1892), 310–311, 303.

- Randolph, Poems, 28–29. For more details on Randolph’s life, see Randolph Family Letters, Harris Papers.

- Susan Randolph to Peyton Randolph, January 10, 1863, series 1, Peyton Randolph Letters, 1863–1884, box 5, folder 4, Harris Papers.

- Davis, “Elegant Old Rebel,” 47; Randolph, Poems, first and second pages of preface.

- “O I’m a Good Old Rebel. A Chant to the Wild Western Melody, ‘Joe Bowers,’” n.d., box 93, item 168, Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Sheridan Libraries and University Museums, Johns Hopkins University, https://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/093/168.

- W. L. Fagan, coll. and arr., Southern War Songs: Camp-fire, Patriotic, and Sentimental (New York: M. T. Richardson, 1890), iii, 361.

- Kevin M. Levin, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 70.

- John A. Lomax, comp., Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads (New York: Sturgis and Walton, 1910), 94–95; Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865 to 1913 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 15–17. By 1934, John A. and Alan Lomax corrected the mistaken identification of “Good Old Rebel” as an anonymous folk poem in their book American Ballads and Folk Songs, and cited Randolph as the author. See John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, comp. and coll., American Ballads and Folk Songs (New York: MacMillan, 1934), 535–540.

- Herbert Quick, “A Good Old Rebel,” Collier’s, April 4, 1914, 20.

- Quick, “A Good Old Rebel,” 21.

- Arthur Palmer Hudson, ed., Folksongs of Mississippi and Their Background (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1936), 253; Donald Davidson, “Current Attitudes Toward Folklore,” in Still Rebels, Still Yankees and Other Essays (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972), 135; E. Merton Coulter, The South during Reconstruction, 1865–1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press and the Littlefield Fund for Southern History of the University of Texas, 1947), 173–174; Davis, “Elegant Old Rebel,” 42–43; Alan Lomax, “From Lead Belly to Computerized Analysis of Folk Song” (lecture, Celeste Bartos Auditorium in New York City, NY, December 31, 1979), http://research.culturalequity.org/get-dil-details.do?sessionId=74.

- Duncan B. M. Emrich, ed., Folk Music of the United States: Anglo-American Songs and Ballads, Library of Congress Music Division Recording Laboratory, AAFS L20, 1947, 331/3 rpm, liner notes; Hermes Nye, Ballads of the Civil War, Folkways Records, FW05004, FP 5004, 1954, 331/3 rpm; Various artists, Songs of the Civil War, Folkways Records, FW05717, FH 5717, 1960, 331/3 rpm.

- Run of the Arrow, directed by Samuel Fuller (1957; Burbank, CA: Warner Archive Collection, 2015), DVD.

- Samuel Fuller, interview by Stig Bjorkman, Movie 17 (Winter 1969–70): 25–29 in Samuel Fuller: Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 10–11.

- The Long Riders, directed by Walter Hill (1980; Beverly Hills, CA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 2001), DVD. The song reappeared in a 2007 film about Jesse James, this time sung by actor Jeremy Renner. See The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, directed by Andrew Dominik (2007; Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. and Warner Home Video, 2008), DVD; Various artists, Songs of the Civil War, Columbia Records, CK 48607, 1991, compact disc.

- “THE THRILLBILLYS – Full Movie,” Jim Stramel, March 31, 2015, YouTube video, 1:13:53, https://youtu.be/NeCqQWrOosQ; The Shiners, Bonnie Blue, Planetary Records, 2001, compact disc; The South Memphis String Band, Old Times There …, Memphis International Records, 2012, compact disc.

- Jimbo Mathus, Confederate Buddha, Memphis International Records, 2011, compact disc. For more on gender performances in southern rock, see Ted Ownby, “Freedom, Manhood, and White Male Tradition in 1970s Southern Rock Music,” in Haunted Bodies: Gender and Southern Texts, ed. Anne Goodwyn Jones and Susan V. Donaldson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 369–388.

- Patterson Hood, “Now, about the Bad Name I Gave My Band,” NPR, June 17, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/06/17/879393187/now-about-the-bad-name-i-gave-my-band.

- Axton, “OH I’M A GOOD OLD REBEL.”

- “I’m a Good Ole’ American (Anti-Obama Song),” piou, August 30, 2009, YouTube Video, 1:50, https://youtu.be/SRtlUi3OJ_c.

- Jeet Heer, “Ironic Nazis Are Still Nazis,” New Republic, November 25, 2016, https://newrepublic.com/article/139004/ironic-nazis-still-nazis; Jane Coaston, “The Proud Boys, the Bizarre Far-Right Street Fighters behind Violence in New York, Explained,” Vox, October 15, 2018, https://www.vox.com/2018/10/15/17978358/proud-boys-gavin-mcinnes-manhattan-gop-violence; Ashley Feinberg, “This Is the Daily Stormer’s Playbook,” HuffPost, December 13, 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/daily-stormer-nazi-style-guide_n_5a2ece19e4b0ce3b344492f2.