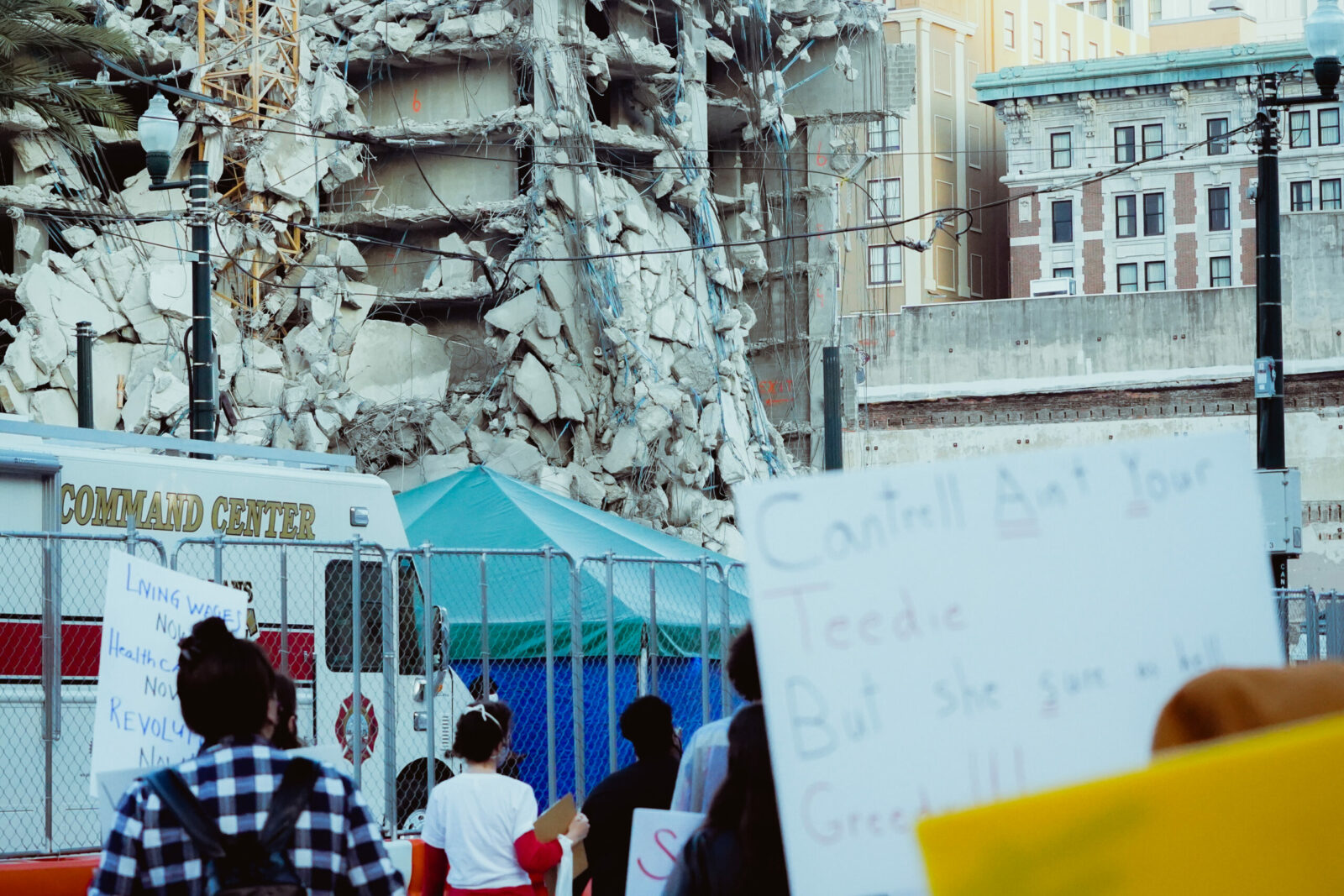

When the body of Jose Ponce Arreola—one of three workers killed during the October 12, 2019 collapse of the Hard Rock Hotel in New Orleans—was finally removed from the hotel ruins in August 2020, the press asked his brother, Sergio, what should be built once the rubble was cleared. Sergio said, “A park dedicated to the workers who died.” The reporter followed up, “No hotel?” He replied pithily, “No.”1

For several months after the collapse, the south-facing side of the unfinished Hard Rock Hotel, located just off the famed French Quarter, remained in ruins, like the smashed end of a layer cake. Thirteen stories of twisted metal beams and crumpled concrete floors contrasted with upright yellow cranes bookending the ruins. The noncollapsed side remained incomplete, its lower levels enveloped in dark violet and gold siding, hinting at the triad of Mardi Gras hues: purple, gold, and green.

As the building collapsed, over one hundred construction workers and pedestrians fled to safety. Buckling floors and falling debris ultimately killed three construction workers—Ponce, Anthony Magrette, and Quinnyon Wimberley—and injured dozens. Yet, before the tragedy, workers had documented the hazardous conditions of a structurally flawed building, sharing footage of beams bending at pressure from too much weight on social media. GIS data showed that three city inspectors signed off on the construction site without ever visiting it. As inspectors, developers, and contractors cut corners, investigations in the aftermath exposed jarring depths of neglect, absence of oversight, and an egregious disregard for human life.2

Joel Ramirez, one of the injured workers, spoke to the media about the dangerous conditions at the worksite. Soon after blowing the whistle, Ramirez, who had resided in the United States for nearly twenty years, was detained and quickly deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) back to Honduras. Until August 2020, the bodies of Wimberley and Ponce remained trapped in the derelict building.

This is a transnational tale of building: the Hard Rock Hotel’s edifice skirting the edge of the touristic French Quarter, partially realized as a multinational corporate project, grounded within centuries of racial capitalism and labor exploitation, and reliant on migrant labor. Outsiders at once lionize New Orleans for its indefatigable merriment and tolerance for gluttony, which Lynnell L. Thomas calls “desire,” while simultaneously reproaching the city for its corruption, racial capitalism, and narratives of violence, which Thomas calls “disaster.” Locals feel a complex and sometimes unconditional love for this precise messiness that creates the place’s joie de vivre. As paradoxes abound, desire becomes commodified, whitewashed, and central to tourism narratives while funds are diverted from the public sector.3

Thus, this is also a tale of unbuilding, a great undoing of government in favor of privatization, a chiseling away at public oversight and workers’ rights. Deregulation in the name of economic development stretches beyond New Orleans to Honduras, where residents have been displaced because corporations have seized land in a bid to capitalize on an ever-hungry tourism industry.

Extractive policies and efforts to privatize often take place on a global scale, spanning from “banana republics” to rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Katrina. Situating the US South within the circum-Caribbean region and linking places like Honduras (where Ramirez is from) and

New Orleans (where he settled) reveals the Hard Rock Hotel site’s place within far-reaching historical and transnational contexts. Addressing the political economy of redevelopment in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, George Lipsitz suggests that city officials and private developers used the city’s Black culture to promote its tourism industry while displacing the same people who made this rich history possible.4 Lipsitz shows how racial capitalism—capitalist accumulation made possible through systemic racial subordination and exploitation—is employed through the extractive tourism industry in concert with megaprojects, multinational hotels, and other corporate chains that take precedence over the people, labor, and history that make a place meaningful. New Orleans’s history as a central port in the trans-Atlantic slave trade has played a role in centuries of segregation and racial inequity that persist to the current era, as the uneven effects of Katrina’s destruction and displacement highlight. Racial capitalism presently unfolds via deregulation and privatization that has occurred since the 1970s, further entrenching inequality in the aftermath of Katrina and beyond. Experiences of exploitation, appropriation, and corruption are reminiscent of similar circumstances in the places migrants leave behind. Examining labor flows between Central America and the US South reveals parallels between extractive practices in these two postdisaster contexts on a global scale.4

The Long Road to the Hard Rock Hotel

The fall of the Hard Rock Hotel begins with the troubled legal history of its developer. The majority owner of the hotel, Mohan Kailas, operated with his team under 1031 Canal Street Developers, one of many LLCs used for his more than one hundred residential and commercial ventures across the city. The LLC hides his own name, one that is tattered by hundreds of thousands of dollars of unpaid inspection fees and questionable political contributions. One of these shady dealings led to the 2013 conviction of Mohan Kailas’s son, Praveen, for conspiracy and theft of public funds from the post-Katrina Road Home project, the largely failed government program that funded homeowners to either rebuild or sell their damaged homes. During the sentencing, which sent Praveen to federal prison for thirty days, the judge scolded Mohan, accusing him of letting his son take the fall for him.5

Kailas’s reach extends to the halls of city government. Investigative reporters for the Lens linked almost $70,000 of campaign donations from Kailas to Mayor Latoya Cantrell along with over $20,000 of donations to former and current city council members. City council votes were essential to grant Kailas the right to begin building the two hundred–foot Hard Rock Hotel building that defied zoning regulations (then capped at seventy-five feet) and Historic District of Landmarks Commission standards, including the right to demolish the building already onsite. To make way for the hotel, Kailas’s team bulldozed the historic deco-style Woolworth building where the Congress on Racial Equality led the first New Orleans sit-ins protesting racial segregation on September 9, 1960. No memorial has ever been erected to commemorate the New Orleans sit-in.6

In 2018, Kailas unveiled designs for an eighteen-story, 350-room, mixed-use development with the Florida-based Hard Rock International. The Hard Rock Hotel is an expansion of the multinational Hard Rock Café Inc., a global chain that occupies the entertainment center of almost every major city and offers a cookie-cutter corporate experience filled with guitars, hamburgers, and memorabilia. You know the T-shirt. The head of Hard Rock Hotel’s development explained the corporation’s aspirations: “As Hard Rock continues to expand globally, our focus will be influential cities with deep musical roots,” and described New Orleans as “home to a unique melting pot of cultures.” The Hard Rock Hotel brings a corporate homogeneity to a city that is anything but mass-produced. As developers like Kailas build over local histories and foster the arrival of salable cultural spaces, they also use a precarious workforce to carry out this corporate vision in the wake of post-Katrina’s urban restructuring.7

Rebuilding in Post-Katrina New Orleans

Workers in post-Katrina New Orleans’s construction and hospitality industries come up against wage theft, work injury, and, for undocumented workers, constant insecurity due to possible detainment and deportation. These experiences, however, are far from anomalous. After the levees broke in 2005, the Bush administration immediately suspended federal labor regulations that guaranteed prevailing wages and Occupational Safety and Health Administration protections. Black workers, who make up the bulk of New Orleans’s working class, faced flooded homes and massive layoffs. The forced displacement of these workers, coupled with the suspension of federal policies to protect labor, led to their replacement with migrant workers. A new, post-Katrina labor force saw tens of thousands of migrants working under massive deregulation and an increasingly draconian federal immigration machine. Many of the immigrant workers who risked life and limb working in the dangerous sector of cleanup and rebuilding stayed in New Orleans and, like Ramirez, settled in neighborhoods and started families. Well over a decade after Katrina, a robust construction industry and bustling tourism sector have kept these immigrants employed.8

Yet, whether in construction or hospitality, low-wage workers experience highly abusive conditions. With average pay well below the living wage, service work in the hotel industry is also characterized by a lack of paid sick days, paid vacation days, benefits, promotions, and the ability to set regular working hours. Exploited workers who build the hotels construct the same walls that lock in the low-wage, overworked staff who prepare etouffees, Sazerac cocktails, and plush accommodations for tourists.

Across the United States, right-to-work laws make it exceedingly difficult to organize unions. New Orleans’s hotels employ 11,647 people, or about 5.6 percent of the city’s jobs. While worker-centered organizations like the New Orleans Hospitality Workers Alliance offer some support for low-wage workers, only three hotels—Harrah’s, Hilton Riverside, and Loew’s—of a staggering 161 are unionized. For the construction industry, subcontracting became common during the deregulation that began in the 1980s. The number of unionized construction workers dropped from 80 percent in 1973 to 14 percent in the early 2010s, even while the number of construction workers doubled. This overall decline in unionization in New Orleans mirrors national trends that began in the 1970s and have continued through the twenty-first century.9

Louisiana’s big business agendas block a state minimum wage and state-level Department of Labor. Little to no public funding is made available for worker organizations or legal services for low-wage earners. Along with right-to-work laws in the US South, policies that favor capital over labor, such as tax incentive schemes, bring an increased corporate presence with the promise of creating jobs. Politicians and key stakeholders’ concerns center on bringing in corporate revenue that attracts outsiders, rather than supporting small, locally-owned businesses. Heralded for creating 250 jobs, recently retired and beloved Saints NFL quarterback Drew Brees opened eight Champaign, Illinois–based Jimmy John’s franchises across the po-boy city.10

Yet, these policy decisions are rooted in histories of exploitation and neglect. In the words of Natalie, a labor organizer and lawyer, the systems themselves are “built to keep people poor so that they’ll continue to work shitty jobs that they don’t get paid for. This is the economy of the South. That has been the economy of the South since England and Spain and everyone colonized it, right?” Natalie helped to run a voluntary Wage Claim Clinic in New Orleans in the mid-2010s helping workers—documented or not—receive back pay, overtime, or a range of other due compensation that falls under the umbrella term of “wage theft.” Many of the workers seeking help at the clinic were construction workers, not unlike Magrette, Wimberley, Ponce, and Ramirez. Others were hospitality workers, laboring in hotels, restaurants, bars, and other entertainment venues. For many of the labor lawyers and federal employees volunteering at places like the Wage Claim Clinic, the experience of measuring and acting against disparities is Sisyphean.11

The decline of workers’ rights paralleled a nationwide increase in undocumented immigration and simultaneous detention and deportation under the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Post-9/11 policy changes under Bush, including the creation of Homeland Security and ICE, ushered in a particularly draconian era of immigration enforcement that took aim at postdisaster worksites. Rhetoric of illegality and deportability become a disciplinary mechanism to produce pliable, exploitable workers. Ramirez’s forced removal after speaking out against shoddy workplace conditions reveals a more explicit form of deportation based on retaliation. Under the Trump administration, over twenty immigrant rights activists entered deportation proceedings as punishment for their activism.12

Yet, such worker struggles have not meant a dearth of political resistance. After Hurricane Katrina, Black workers, largely shut out of the rebuilding, and immigrants, subject to unsafe working conditions, organized under the larger umbrella of the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice (NOWCRJ). Though just one actor within a larger patchwork of vibrant social justice organizing, their multiracial solidarity organizing has led to lasting changes in local city governance. The Congress of Day Laborers, a suborganization of NOWCRJ led by undocumented migrants in the city, launched a campaign to stop Ramirez’s deportation. While the campaign proved unsuccessful, it united local nonprofits, building trade union members, and undocumented workers. The movement exposed the gravity of deporting Ramirez and illustrated how ICE, acting as an arm of the state weaponized for the business sector, silenced a crucial witness. Today, Ramirez, forced to leave his wife and three kids behind, is living in Honduras after speaking out about the unsafe work conditions of the very building that killed his colleagues.

Like New Orleans, the Honduran state has instituted “open for business” policies and pushed for the expansion of extractive tourism industries that operate at the expense of poor and working-class communities. Just as Hurricane Katrina led to a disaster capitalism complex that included deregulation, extreme privatization, and the dismantling of the public sector, Hurricane Mitch, which devastated Honduras in 1998, led to increased privatization and dispossession of Honduran lands by these tourism industries. The aftermath of the 2009 coup of Manuel Zelaya, whose administration sought to redistribute and better protect land from corporations, further expedited these reforms, ushering in over a decade of austerity and unfettered corporatism. This shift to a highly privatized market-based economy with a significantly weakened public sector has contributed to the instability and displacement that forced people to leave the country in search of opportunity in cities like New Orleans—including construction work on the Hard Rock Hotel.13

Tracing Legacies of Graft, Development, and Displacement to Honduras

Just over fifty miles northeast of Ramirez’s current home in the Department of Yoro is Indura Beach and Golf Resort, a high-end hotel and spa that occupies over twenty-six miles of Honduras’s Caribbean coast. According to Indura’s website, the beach resort’s “overall design remains true to the region’s history,” a reference that unwittingly connects to the banana trade and neocolonial history of United Fruit Company (UFC), now Chiquita Brands. Headquartered in New Orleans for much of the twentieth century, UFC’s plantations and offices spread along the same coastal lands where Indura now resides.14

Indura is a lavish display of abundance with faux-thatched roofs, eco-adventures, and an 1,800-acre, eighteen-hole golf course; all situated in a region plagued by corruption, violence, poverty, and environmental devastation. Initially sponsored by the Honduran government, private investors, and partial funding from the Inter-American Development Bank, the hotel is now part of the upscale Curio Collection by the multinational Hilton Hotel conglomerate.

On its website, Indura boasts that its wellness spa treatments reflect Honduras’s “mélange of cultural influences”—influences built upon the ancestral lands of the Garifuna, Black Indigenous people exiled from Yurumein (now St. Vincent) Island by the British in 1797 and forced to Roatan, a small island off the coast of Honduras. The Garifuna people eventually settled across coastal Central America, establishing their own villages and cultural practices that include traditional dances, foods, and the preservation of their language that showcases their Carib and Arawak roots. Since 2001, the Garifuna language, dance, and music have been protected under UNCESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.15

Even though some Garifuna communities were granted territorial rights through the Honduran constitution to hold communal land titles in perpetuity, a mushrooming tourist industry—empowered by a corrupt government and corporatism—has sought out their beachfront property and slowly chipped away at their land. Since this restructuring, which began in the mid-1990s, Black Indigenous people have struggled against Indura’s expansion because, much like the Hard Rock Hotel, Indura’s developers thrive on cronyism and deregulation. These local communities have been razed to make way for more hectares of golf courses, bike paths, and palm tree–lined protections for tourists. Along with real estate speculation, the expansion of palm oil plantations and deregulation of gas and oil industries have led to irreversible environmental devastation of wetlands and mangroves while also engendering violent land grabs that threaten the local Garifuna communities. All this happens with the support of the procorporatist Honduran government.16

Groups like OFRANEH (Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras) and COPINH (Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras) have fought against privatization efforts only to be violently targeted by militarized forces and private companies working in tandem with the Honduran state. Notably, Berta Cáceres, a Honduran activist and winner of the illustrious international environmental award the Goldman Prize, was murdered point blank in 2015 for her activism to end the construction of a hydroelectric dam project proposed by the private energy company DESA. David Castillo Mejia, a Honduran ex-military intelligence officer (trained at West Point) and president of DESA, was charged for her murder and awaits trial.17

More recently, in early June 2020, Garifuna leader Antonio Bernádez, who fought relentlessly for land rights and whose daughter is an activist in New Orleans, was murdered in what many consider retaliation for his activist work. Just weeks later, five Garifuna leaders were kidnapped on July 19, 2020, and forced at gunpoint from their respective homes into unmarked vehicles. The leaders’ whereabouts are still unknown. In New Orleans, those who speak out against labor abuses and unfettered capitalism are subject to deportation. In Honduras, this activism can be fatal.18

At Barra Vieja, a local Garifuna village that the Indura expansion has slowly swallowed, thatch-roofed houses made of wood scatter the beachfront property. With a squint, the fencing for the giant Indura hotel complex is visible, ensconced by the dense, pruned foliage that evokes a mutable yet protected divide. In 2014, local military officials violently evicted Garifuna communities from their Barra Vieja and Miami beachside villages. One community leader described the event in detail, explaining how members of the military woke him up and kicked him out of his home in the middle of the night. When he was able to return, his beachfront thatched-roof hut was completely leveled. The raids were meant to intimidate the community off their land, which is attractive real estate to Indura’s expanding massive compound. In many cases, intimidation has proven successful; an estimated fifty thousand Garifuna people have migrated to the United States, with two to four thousand Garifuna people living in New Orleans.19

One of the few remaining hopes for the Barra Vieja community is its recognition as a historical site by the Tela Municipality since 1950, a status that gave Barra Vieja temporary reprieve from the local court after the 2014 raids. In 2015, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) ordered compensation for Garifuna land that was stolen and that more binding titles to the land be given to Garifuna people to better ensure protections. But little has been done to protect these lands and people because of the entrenched power of corporate interest coupled with the political limitations of organizations like UNESCO.20

While mainstream media’s narratives of Central American migration tend to focus on gang violence, land annexation by tourism industries and palm oil plantations, often realized with state support, drive migration as well. Touted for the profits they’ll bring to local communities, tourism development projects instead push people from their lands and threaten local communities. Nevertheless, deeming Garifuna land use unproductive and reinforcing job creation through the hotel industry provides justification for developments like Indura.

A New Rebuilding?

The migratory paths that lead out of Honduras to cities like New Orleans enmesh these seemingly disparate locations, building upon one another in a transnational web of capital, goods, and people. Often thought of as destinations ripe with potential for touristic consumption, both New Orleans and coastal Honduras are much more than the commodified sum of their parts. Much of what makes New Orleans and northern Honduras attractive to tourists has been possible because of Black and Indigenous cultural production. Commodification erases and dilutes complex histories; ersatz gestures fail to preserve local practices. Using the word “Indura,” which means “Honduras” in the Garifuna language, does nothing to mollify and only furthers the dispossession of the Garifuna people.

Nothing makes this erasure starker than the deportations, silencing of activists, and deaths of workers for the sake of crony capitalism. Victims of racial capitalism are connected to one another via multiracial organizing but also by local governments that bend to corporate interests, low-wage and unsafe work masquerading as “good jobs,” residential displacement, lack of public investment, the silencing of dissent, and the construction of new buildings atop land sacred to local communities, whether referring to Garifuna ancestral land in Central America or the site of a seminal civil rights protest in New Orleans. Built environments expose the fact that extractive development projects are global in scope.

In Jamaica Kincaid’s short 1988 memoir, A Small Place, she offers a scathing critique of tourist industries in her homeland of Antigua, a small island in the Caribbean. Kincaid is particularly critical of Antigua’s Hotel Training School, arguing that it wants to teach “students how to be good servants.” Kincaid posits, “In Antigua, people cannot see a relationship between their obsession with slavery and emancipation and their celebration of the Hotel Training School; people cannot see a relationship between their obsession with slavery and emancipation and the fact that they are governed by corrupt men, or that these corrupt men have given their country away to corrupt foreigners.” In a 1991 interview, Kincaid explained how the Hotel Training School replaced Antigua’s only Teacher’s Training College, which can be interpreted as the unbuilding of an institution that made its local community strong.21

In the case of Kincaid’s story, many of the workers, their families, and the land protectors had long been wary of the false promises of establishments like the Hotel Training School. Proponents of corporatist privatization perpetuate exploitative tourism industries at the expense of local people, culture, and economies. Emancipation histories are bulldozed, wages remain stagnant, inequality grows, and developers operate with no oversight.

Sergio, the brother of Ponce who was killed in the collapse, gives us an alternative to a new hotel: a park built in memory of the workers. As of March 30, 2021, and in the final stages of demolition, no plans for memorialization were underway. By integrating local histories, such a park could be a tribute to workers of all kinds, including the five individuals who sat at the counter at Woolworth’s in defiance of segregation and Jim Crow. But efforts to redress injustices must go beyond symbolic parks and plaques. They must be built and rebuilt as policies—living wages, access to healthcare, worker protections, secure land titles—that better protect local communities from extractive economies on a global scale.22

This essay first appeared in the Built/Unbuilt Issue (vol. 27, no. 2: Summer 2021).

Deniz Daser is an anthropologist who studies migration, labor, and citizenship. She is an external lecturer at University of St. Gallen and holds a PhD in anthropology from Rutgers University. Her dissertation, “Leveraging Labor in New Orleans: Worklife and Insecurity among Honduran Migrants,” drew upon extensive fieldwork in New Orleans.

Sarah Fouts is assistant professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and holds a PhD in Latin American studies from Tulane University. Fouts is currently working on a book manuscript on labor, migration, food, and transnationalism in post-Katrina New Orleans and Honduras.

Header: View of the collapsed Hard Rock Hotel construction site, February 2020. Photograph by Kelly van Dellen, from Alamy Stock Photo.NOTES

1. “Brother of Jose Ponce Arreola Discusses Recovery of Remains,” WWL-TV, August 18, 2020, https://www.wwltv.com/video/news/local/orleans/hard-rock-collapse/brother-of-jose-poncearreola-discusses-recovery-of-remains/289-3ac6d30a-74aa-42f6-aeaa-07f679536b5f.

2. Randy Gaspard, “Days Prior to Hard Rock Collapse, Citadel Well Aware of a Problem, Profits Over Safety, Sad!,” Facebook, October 15, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/randy.gaspard.311/videos/173870670402890/?t=8; Lee Zurik and Cody Lillich, “Zurik: Third City Inspector Likely Did Not Visit Hard Rock Site when He Signed Off on Work,” Fox8live, last modified February 20, 2020, https://www.fox8live.com/2020/02/20/zurik-third-city-inspector-likely-did-not-visithard-rock-site-when-he-signed-off-work/; Jules Bentley, “Built to Kill: The Hard Rock Collapse Is Simply Business as Usual for Louisiana,” Antigravity, November 2019, http://antigravitymagazine.com/feature/built-to-kill/.

3. Lynnell L. Thomas, Desire and Disaster in New Orleans: Tourism, Race, and Historical Memory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014); Deniz Daser, “Citizens of the City: Undocumented Latinx Migrants Organising Politically in Post-Katrina New Orleans,” Public Anthropologist 3, no. 1 (March 2021): 148–176; Rachel Breunlin and Helen A. Regis, “Putting the Ninth Ward on the Map: Race, Place, and Transformation in Desire, New Orleans,” American Anthropologist 108, no. 4 (December 2006): 744–764. Sarah Fouts is currently working on a book-length manuscript that explores these frameworks in greater depth.

4. Kirsten Silva Gruesz, “Converging Americas: New Orleans in Spanish-Language and Latina/o/x Literary Culture,” in New Orleans: A Literary History, ed. T. R. Johnson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 137; George Lipsitz, How Racism Takes Place (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 236–237; Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore, “Cities and the Geographies of ‘Actually Existing Neoliberalism,’” Antipode 34, no. 3 (July 2002): 349–379. On racial capitalism, see Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983).

5. “Kailas Companies | Real Estate Development & Management,” Kailas Companies, accessed April 13, 2021, https://www.kailascompanies.com/; “Developer, Praveen Kailas, Sentenced to 30 Months for Theft of Government Funds and Conspiracy Charges,” United States Department of Justice, December 18, 2013, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edla/pr/developer-praveen-kailassentenced-30-months-theft-government-funds-and-conspiracy; Timothy F. Green and Robert B. Olshansky, “Rebuilding Housing in New Orleans: the Road Home Program after the Hurricane Katrina Disaster,” Housing Policy Debate 22, no. 1 (February 2012): 75–99; David Hammer, “Hard Rock Hotel Developer’s Troubled Past First Exposed by WWL-TV,” WWL-TV, October 16, 2019, https://www.wwltv.com/article/news/local/orleans/hard-rock-developer-had-troubled-pastexposed-by-wwl/289-834e15ba-3a60-4dff-9bbf-648d400565c5. In January 2020, Kailas was ordered by a judge to stop harassing tenants in a property he owned. Just a block away from the collapse, the thirty-one-story International Style skyscraper towers over the French Quarter, a stark contrast to the assemblage of wrought iron balconies, Creole cottages, and Greek Revivalist–style structures that give the Vieux Carre its charm. Kailas sought to vacate tenants who had occupied the high-rise property for over a decade in order to demolish the interior apartments and offices and make way for two more hotels. Anthony McAuley, “Stop Harassing Tenants at 1010 Common, Judge Orders Hard Rock Developer Kailas,” Times-Picayune, January 24, 2020, https://www.nola.com/news/business/article_29c4d89e-3ed9-11ea-8802-07cdef30ed8e.html.

6. Michael Isaac Stein, “Hard Rock Developers Have Contributed Nearly $70,000 to Mayor Cantrell and Her Political Action Committee,” Lens, January 28, 2020, https://thelensnola.org/2020/01/28/hard-rock-developers-have-contributed-nearly-70000-to-mayor-cantrell-and-her-political-action-committee/; McAuley, “Stop Harassing Tenants.”

7. Richard Thompson, “Plans Unveiled for Hard Rock Hotel, New Orleans: 18 Floors, 350 Rooms on Canal Street,” Advocate, February 15, 2018, https://www.nola.com/article_782b5dbc-9d2a-59e2-96a5-9b6048df5007.html; “Hard Rock International Plans French Quarter Hotel and Residences in 2019,” Canal Street Beat, February 20, 2018, https://canalstreetbeat.com/hard-rock-international-plans-french-quarter-hotel-and-residences-in-2019/.

8. Leo B. Gorman, “Latino Migrant Labor Strife and Solidarity in Post-Katrina New Orleans, 2005–2007,” Latin Americanist 54, no. 1 (March 2010): 1–33; A. L. Murga, “Organizing and Rebuilding a Nuevo New Orleans: Day Labor Organizing in the Big Easy,” in Working in the Big Easy: The History and Politics of Labor in New Orleans, ed. Thomas J. Adams and Steve Striffler (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2014), 211–227; Daser, “Citizens of the City.”

9. Erin Moore Daly, “New Orleans, Invisible City,” Nature and Culture 1, no. 2 (Autumn 2006): 135; Rebecca Torres et al., “Building Austin, Building Justice: Immigrant Construction Workers, Precarious Labor Regimes and Social Citizenship,” Geoforum 45 (March 2013): 147. In the twenty-year period between 1977 and 1997, the number of jobs in tourism went from 22,488 to 35,824, an increase of 60 percent. In the period between 1994 and 2002, hotel rooms in the city increased 40 percent. David Gladstone and Jolie Préau, “Gentrification in Tourist Cities: Evidence from New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina,” Housing Policy Debate 19, no. 1 (2008): 140, 139. Globally, of the twenty-two (and eleven under construction) Hard Rock Hotels, only one, located in Atlantic City, is unionized. Robert Habans and Allison Plyer, “Benchmarking New Orleans’ Tourism Economy: Hotel and Full-Service Restaurant Jobs,” Data Center, December 2018, https://s3.amazonaws.com/gnocdc/reports/benchmarking-tourism-brief-habans-et-al.pdf.

10. Daser, “Citizens of the City”; Jade Scipioni, “NFL’s Drew Brees Is Not Only a Passing Legend but also a Savvy Investor,” Fox Business, October 9, 2018, https://www.foxbusiness.com/features/nfls-drew-brees-is-not-only-a-passing-legend-but-a-savvy-investor.

11. Deniz Daser, “Leveraging Labor in New Orleans: Worklife and Insecurity among Honduran Migrants” (PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2018).

12. John Burnett, “See the 20+ Immigration Activists Arrested under Trump,” NPR, March 16, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/03/16/591879718/see-the-20-immigration-activists-arrested-under-trump. For more on deportability, see Daniel M. Goldstein and Carolina Alonso-Bejarano, “E-Terify: Securitized Immigration and Biometric Surveillance in the Workplace,” Human Organization 76, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 1–14; and Nicholas P. De Genova, “Migrant ‘Illegality’ and Deportability in Everyday Life,” Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (October 2002): 419–447.

13. Adam Davidson, “Who Wants to Buy Honduras?,” New York Times, May 8, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/magazine/who-wants-to-buy-honduras.html; Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Henry Holt, 2007); Christopher A. Loperena, “Honduras Is Open for Business: Extractivist Tourism as Sustainable Development in the Wake of Disaster?,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25, no. 5 (2017): 618–633; “Ten Years after the Honduran Coup: Selected Readings,” North American Congress on Latin America, June 28, 2019, https://nacla.org/news/2019/06/28/ten-years-after-honduran-coup-selected-readings.

14. “Nestled Oceanside in Beautiful Tela Bay, Honduras,” Indura Beach & Golf Resort, accessed April 14, 2021, http://induraresort.com/m/.

15. “Spa & Wellness,” Indura Beach & Golf Resort, accessed April 14, 2021, http://www.induraresort.com/spa-wellness.html.

16. Loperena, “Honduras Is Open for Business.”

17. Beth Geglia, “As Private Cities Advance in Honduras, Hondurans Renew Their Opposition,” Center for Economic and Policy Research (blog), December 3, 2020, https://cepr.net/as-private-cities-advance-in-honduras-hondurans-renew-their-opposition/; Beth Geglia, “Honduras: Reinventing the Enclave,” NACLA Report on the Americas 48, no. 4 (October 2016): 353–360; Nina Lakhani, “Honduras: Accused Mastermind of Berta Cáceres Murder to Go on Trial Next Month,” Guardian, March 2, 2021, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/02/berta-caceres-honduras-accused-mastermind-trial.

18. Anastasia Moloney, “Honduran Minority Fears for Survival after Leaders Abducted,” Reuters, July 31, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-honduras-landrights-violence-trfn-idUSKCN-24W1OG.

19. Interview with Garifuna community leader conducted during Sarah Fouts’s fieldwork to Barra Vieja and the Atlántida region of Honduras in July 2015. Population numbers for the Garifuna people in the United States are hard to track based on census data because Garifuna don’t fit the rigid identity structure of census formats. James Chaney’s work cites an estimate from 1997 for the New Orleans data on Garifuna people in New Orleans; however, the numbers are likely much higher. Nationwide statistics approximate one hundred thousand people. For New Orleans Garifuna information, see James Chaney, “Malleable Identities: Placing the Garínagu in New Orleans,” Journal of Latin American Geography 11, no. 2 (2012): 128. For information on Garifuna in New York, see David Gonzalez, “Garifuna Immigrants in New York,” Lens (blog), July 24, 2015, https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/07/24/garifuna-immigrants-in-new-york/. For information on Garifuna and the US census, see “Garifuna and the 2020 Census,” PhilanTopic (blog), Candid, December 2, 2019, https://pndblog.typepad.com/pndblog/2019/12/garifunas-and-the-2020-census.html.

20. James Rodríguez, “Garifuna Resistance against Mega-Tourism in Tela Bay,” North American Congress on Latin America, August 5, 2008, https://nacla.org/news/garifuna-resistance-against-mega-tourism-tela-bay; “The Garifuna Community of Barra Vieja on Trial for Defending Ancestral Territory,” Latin America in Movement, April 6, 2015, https://www.alainet.org/en/articulo/170135?language=en; Proah, “The Garifuna Community of Barra Vieja on Trial for Defending Ancestral Territory,” Latin America in Movement, April 6, 2015, https://www.alainet.org/en/articulo/170135?language=en.

21. Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988), 55; Allan Vorda and Jamaica Kincaid, “An Interview with Jamaica Kincaid,” Mississippi Review 20, no. 1/2 (1991): 7–26.

22. Jeff Adelson and Jessica Williams, “The Hard Rock Hotel Collapsed 17 Months Ago; Now Demolition Nears Its End,” NOLA, March 30, 2021, https://www.nola.com/news/politics/article_8ae71346-91b0-11eb-a2f8-67fa982790f9.html. For information on how other activist groups have suggested a similar way of memorializing, see Justin Montrie, “Call for Public Hearing on the Hard Rock Hotel Disaster | Call for a Community Rights Park,” Change.org, accessed August 30, 2020, https://www.change.org/p/the-people-call-for-public-hearings-on-the-hard-rock-hotel-collapse-this-isa-call-for-a-community-rights-memorial-park-at-1031-1041-canal.