Grey Gardens, the house first made famous by the 1975 documentary on the lives of Jackie Kennedy’s aunt and cousin—better known as “Big Edie” and “Little Edie” Beale—is, in many ways, familiar in southern culture. The story of the Beales and their derelict home in East Hampton, New York, later dramatized in the 2009 hbo film of the same name, might have been drafted for a novel set in the South. Although born into wealth and privilege, the social and economic decline that befell mother and daughter was not unlike that which many southern families faced following Confederate defeat and the end of slavery. Add to this that the Beales became reclusive and seemed resigned to living in the filth and decay that surrounded them and you have the makings of a gothic novel.

The story of the Beales and the condition of Grey Gardens was, in many ways, reminiscent of the kind of story once only associated with a crumbling Old South. Decades before the story of Big and Little Edie made headlines, William Faulkner’s fictionalized accounts of the region provided a stark contrast to the romantic South many Americans loved in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind. His novel The Sound and the Fury and his short story “A Rose for Emily” were peopled with grotesque characters whose personal decline was a reflection on the region itself. It was through this binary lens of both the romantic and benighted South that Americans in the 1930s saw the region. Popular culture—particularly literature, film, and theater—informed what was, for all intents and purposes, these mythic perceptions. And yet, even as Faulkner rose to prominence, there was a very real story of southern degradation and decay that made national headlines in the fall of 1932—long before Americans learned of Big and Little Edie and the life they lived in the shadows of Grey Gardens.

That earlier story involved a feud fought between aging southern belles. There was murder, too, and a dilapidated antebellum mansion named Glenwood. The New York Times headline captured what made the case so compelling to readers: “Neighbor Pair Held in Natchez Murder, R. H. Dana and His Housekeeper Charged with Slaying Miss Merrill Over Goats. Three Members of Aristocratic Families, All 60 or More, Lived Lives as Recluses.” Here were Faulknerian characters come to life.1

Natchez, Mississippi, was by any definition a small town. Its population was little more than thirteen thousand the year the crime took place. Yet, it had once been one of the wealthiest towns in the nation, per capita, prior to the Civil War. The reason? Cotton and slavery. Both local southerners and northern investors from New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania sought out this small town that sits atop the bluffs of the Mississippi River, purchased large tracts of land in Louisiana and Mississippi, and built magnificent homes known as “suburban villas” in and around Natchez. They were directly involved in America’s domestic slave trade, which forcibly removed between 750,000 and one million enslaved people from the Upper South to work the plantations they bought in the Deep South. Solomon Northup, who documented his experience in 12 Years a Slave, was one of the many men, women, and children who were victimized by the greed of slave traders and planters.2

Jennie Merrill, the sixty-eight-year-old shot and killed in her home during a botched robbery in August 1932, was descended from Natchez planter aristocracy. The Merrills, originally from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, followed other northerners to the Deep South in search of the riches made possible by the antebellum cotton boom. Despite enslaving nearly six hundred people, her father Ayres P. Merrill Jr. was a staunch Unionist during the Civil War. After the war ended, and even in the face of considerable financial losses, he remained wealthy and a year later returned north and built a second home in Newport, Rhode Island, called Harbor View. He was eventually named U.S. Ambassador to Belgium.3

Jennie Merrill was descended from planter aristocracy on her mother’s side as well. Her maternal grandfather, Frank Surget, was one of the wealthiest men in the nation by 1850. He owned plantations in three states, more than one thousand slaves, and was a millionaire several times over. And while Jennie did not grow up to live the life of a plantation mistress, she nonetheless lived a lavish life and maintained a healthy financial portfolio of stocks, bonds, and land, even during the Depression.4

Her neighbor Octavia Dockery, on the other hand, was less fortunate. Born in Arkansas in 1865, her father, a Confederate general, was financially ruined by the war. His primary investment had been in slaves so that once the war ended, he kicked around trying to make ends meet for the next thirty years only to die penniless in a rooming house in New York. Octavia and her sister Nydia were initially sent with their mother to live with a paternal uncle. When their mother died, they followed their father to New York, where they lived for a dozen years until Nydia married a man her father’s age, a Mississippian named Richard Forman. Octavia returned to the South with her sister and brother-in-law, both of whom would precede her in death. Unmarried and without an income, Octavia had nowhere to turn, except to the man who had long boarded with the Formans, Richard “Dick” Dana. The son of an Episcopal rector, he had become increasingly mentally unstable, yet his inheritance included an estate in Natchez that adjoined Jennie Merrill’s. Dick and Octavia never married, but she did eventually become his legal guardian.

Unlike Merrill’s home Glenburnie and the surrounding property, which was planted with lespedeza and roses and maintained by black servants, Dick and Octavia’s home and estate were dilapidated. Once one of the nicer suburban villas on the outskirts of Natchez, it had long ago descended into shocking condition. The roof leaked, the porches on both the first and second floors were rotting, and the filth of decades of neglect was evident everywhere. Dirty pots and pans were scattered throughout what had been the imposing library of the rector. Cobwebs wafted down from the ceiling and netted the furniture. Chickens and geese made their nests on bookcases and inside an old piano. And then there were the goats. They roamed the house at will, chewing up the wallpaper as far as they could crane their necks. The waste of this menagerie of animals covered the floors.

Dick was of no help to Octavia either. Although described in newspapers as his housekeeper, in truth she was his legal guardian. He’d been declared non compos mentis in 1917 and was difficult to manage. He rarely bathed, let his hair and beard grow long, and he romped around outdoors in a burlap sack with a hole cut out for the head. Men who logged the estate for timber recollected that he hid behind trees when called and that he spent most of his time in the woods surrounding his home, roosting on high tree limbs and swinging from grapevines—an activity he enjoyed well into his fifties.

None of it would have been exposed to the world had it not been for Jennie Merrill’s murder.

From the time Octavia became Jennie’s neighbor in 1916, the two women feuded constantly over trespassing hogs and goats who escaped their deteriorating environs at Glenwood with their sight set on truffles around Merrill’s ponds, as well as her lespedeza and roses. Sheriff’s deputies dealt with the complaints of both women so many times they’d lost count and, only days before her murder, Jennie had a particularly vicious argument with Octavia over the damage the goats had done to her property.

The two women feuded constantly over trespassing hogs and goats who escaped their deteriorating environs at Glenwood.

Then, on the evening of August 4, 1932, Jennie’s cousin Duncan Minor sent a young African American man named Willie Boyd to call the sheriff to Glenburnie. Minor had discovered blood on the floor and walls of Merrill’s home, which had also been ransacked. A posse of deputies formed a search party and, not long after, the sheriff went to interview the neighbors. The feuding between the two women had become so bitter that he believed either Dick or Octavia to be likely suspects.

When he arrived at the ramshackle mansion, it was nearly midnight and the sky was pitch-black. He called out for Dick Dana. There was no answer. He called again. Finally, Dick descended the rickety stairs from the second floor and, before the sheriff had an opportunity to explain why he was there, Dick blurted out, “I know nothing of the murder.” Jennie Merrill’s body had yet to be found. Octavia’s comments were suspicious, too, and the pair was arrested and taken to the Adams County Jail.

Within hours, news of the crime circulated regionally, and then nationally. But the story the media found itself drawn to was not so much the murder of a scion of the Old South, but of the quirky pair who had been arrested and whose home defied belief. The press dubbed him the “Wild Man” and her the “Goat Woman,” and Glenwood “Goat Castle.”5

While the first headlines focused on Jennie Merrill’s death—”Rich Woman Recluse Slain in Mississippi” and “Elderly Recluse Slain in South”—they soon gave way to “Weird Mississippi Murder Traced to Row over Goats” and “Southern Goat Castle Scene of a Tragedy” and others like it. A jailhouse photo of Dick and Octavia accompanied the articles. Stern and unsmiling, Octavia looked like a weathered farmwife. She wore a straw hat and a smock covered her morning dress. Dick’s hair looked unkempt. He had not shaved for several days and he wore filthy coveralls. He sat to her left with his hands in his lap and had a wild-eyed expression that suggested he might be mentally ill.6

From Maine to Montana and places in between, this story of a decaying Old South mired in a grotesque drama of murder, poverty-stricken social elites, and reclusive behavior drew national attention to the small town that prided itself on southern grandeur, not the sideshow that Goat Castle represented.

Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Bruce Catton, a young journalist at the time, asked rhetorically, “Can a novelist have invented a more fascinating, hair-raising tale of decay and morbid gloom than this one from real life?” Indeed, the crime and the circus of Goat Castle provided the public with a counternarrative to moonlight and magnolias. “Once these were famous southern plantations,” Catton observed. “Now they are dilapidated, unkempt, weed-grown, their fine manor houses grown decrepit and gloomy, their imposing driveways bordered with rank grasses and undergrowth.” These homes had become a reflection of the people who inhabited them.7

“Can a novelist have invented a more fascinating, hair-raising tale of decay and morbid gloom than this one from real life?”

Added to this atmosphere were the voyeurs who arrived in Natchez to see Goat Castle mere days after the story broke. The first weekend following Dick and Octavia’s arrest, more than one thousand “tourists”—mostly fellow southerners from Louisiana and Mississippi—poured onto the property and into the house and took items from inside as souvenirs. After spending ten days in jail, the couple returned to their home and, on the advice of “friends,” decided to capitalize on their notoriety. If people wanted to see Goat Castle, they could, for a price. They charged twenty-five cents for admission to the grounds and another twenty-five for entry into the house.

Ultimately, the Wild Man and the Goat Woman were never put on trial—even though their fingerprints were found inside Jennie Merrill’s home—ostensibly protected by their race and connection to southern aristocracy. As was all too typical in the Jim Crow South, an African American person was sentenced for the crime; in this instance, an innocent woman named Emily Burns, who worked as a domestic. Circumstances outside of her control had brought her to the Merrill home that evening, though she never entered the house. Despite a valiant effort by her court-appointed attorney, she was sentenced to life in prison at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, better known as Parchman, subsequently becoming the other victim in this crime. After serving eight years in Parchman, she appeared before Governor Paul B. Johnson’s “mercy court,” where, in December 1940, he suspended her sentence. She returned to Natchez after having served time in one of the most brutal prisons in the South. Burns’s unfair sentencing and relatively unknown role in this story speaks to the devastating effects of racism in the Jim Crow South.

In the years that followed, Natchez would become famous for pilgrimages to its stately homes as tourists from the Midwest and Northeast traveled there to experience antebellum grandeur. But the murder of Jennie Merrill and the spectacle of Goat Castle continued to haunt the town. Several years after the case had been settled, the Saturday Evening Post published an article intended to highlight Natchez’s beautiful antebellum mansions and play up its association with the Old South. Even so, the article could not help but make mention of the scandal that brought the town such unfavorable attention. “For twenty-five cents the visitor may see another old mansion, Glenwood, better known since 1932 as Goat Castle, a side show which might have been plagiarized from a story by William Faulkner.” Tucked in between beautiful photographs of homes and gardens, the article referenced Jennie Merrill’s murder and reminded readers that while Dick Dana “was absolved of the crime,” it did not happen “before squalorous [sic] Goat Castle had been described in word and photograph in every paper in America.” This, of course, reflected poorly on Natchez’s white citizens, who had a vested interest in preserving an image of the town, and subsequently the region, as an authentic representation of the Old South since the local economy depended on the tourism it attracted. And while that image seems to have won out, the town never fully escaped its association with the fallen South.8

America’s fascination with the Southern Gothic has a long history. It began in the nineteenth century with stories by Edgar Allan Poe and continued in the twentieth with the fiction of William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor. It has also found its place on the big screen in films from Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte to the most recent adaptation of The Beguiled. More recently, the podcast S-Town offered a twisted version of the Southern Gothic in a small Alabama town, to the delight of millions. That the gothic continues to pique our interest is a testament to its longevity as a compelling way to see the South that represents a shocking contrast to the romantic image of cavaliers and southern belles that Gone With the Wind inspired for decades. But as Goat Castle reminds us, this counternarrative is not that far from the truth.

This essay was published in the Here/Away Issue (vol. 25, no. 4: Winter 2019).

KAREN L. COX is professor of history at UNC Charlotte. She is the author of several books and articles on the American South, including most recently Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South.

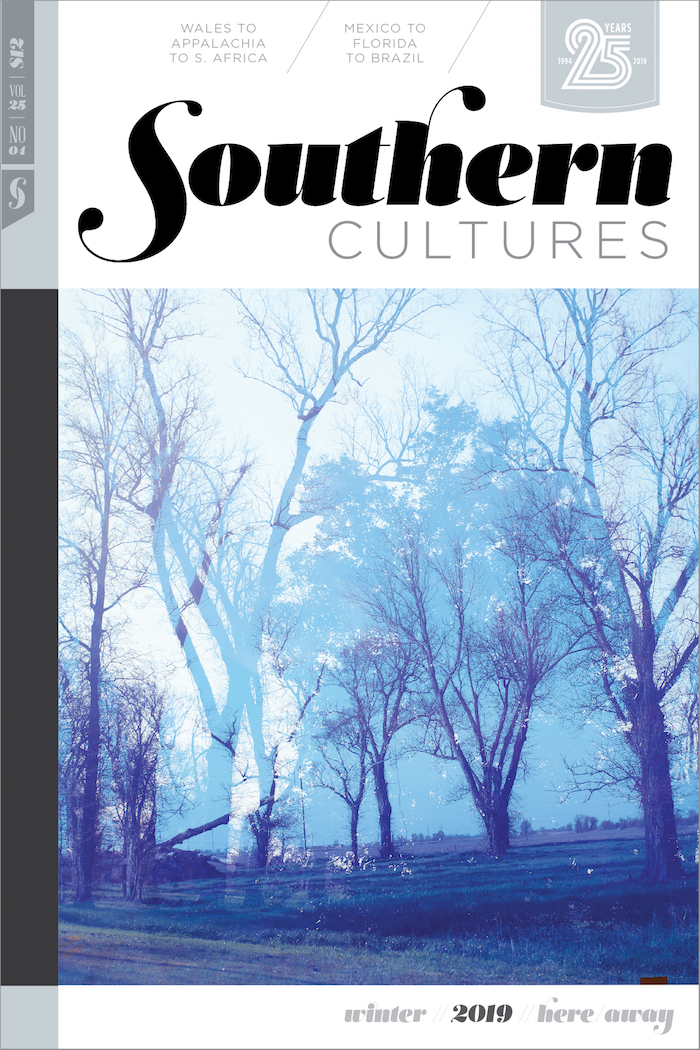

Header image: Glenwood “Goat Castle,” August 1932. Earl Norman Photograph Collection, Historic Natchez Foundation, Natchez, Mississippi. Courtesy of the Historic Natchez Foundation.NOTES

- “Neighbor Pair Held in Natchez Murder,” New York Times, August 9, 1932.

- The U.S. Federal Census for 1930, found on ancestry.com, showed Natchez’s population was 13,422; Jonathan B. Pritchett, “Quantitative Estimates of the United States Interregional Slave Trade, 1820–1860,” Journal of Economic History 61, no. 2 (June 2001): 467–475.

- According to the 1900 U.S. Federal Census, available at ancestry.com, Jennie was born in August 1863. On the Merrills, see William Kauffman Scarborough, Masters of the Big House: Elite Slaveholders of the Mid-Nineteenth-Century South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2003), 11–12, 100. Regarding Merrill’s slaveholdings, see U.S. Federal Census 1860—Slave Schedules, Adams County on ancestry.com.

- On the Surgets, see Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi, vol. 2 (Chicago: Goodspeed, 1891), 430–431; U.S. Federal Census—Slave Schedule, 1850.

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), August 6, 1932.

- “Rich Woman Recluse Slain in Mississippi,” New York Times, August 6, 1932; “Elderly Recluse Slain in South,” Joplin (MO) Globe, August 6, 1932; “Weird Mississippi Murder Traced to Row over Goats,” Helena (MT) Independent, August 8, 1932; “Southern Goat Castle Scene of a Tragedy,” Lebanon (PA) Semi-Weekly News, August 15, 1932.

- Bruce Catton, “A Story Stranger than Fiction,” Freeport (IL) Journal Standard, August 15, 1932.

- Ivan Dmitri, “So Red the Rose,” Saturday Evening Post, March 4, 1939, 18–23.