I was in college when I first learned that my great-grandmother, Lydia Andrews, who my father and his siblings and cousins called Ganny, was born on the United Fruit Plantation in Puerto Limón, Costa Rica. Before Papi shared this fact with me, I knew Ganny only in small glimpses of family memory that seemed to contract the world in which she existed, such that she existed only in ours—that is, she belonged specifically to my family, and not to history.

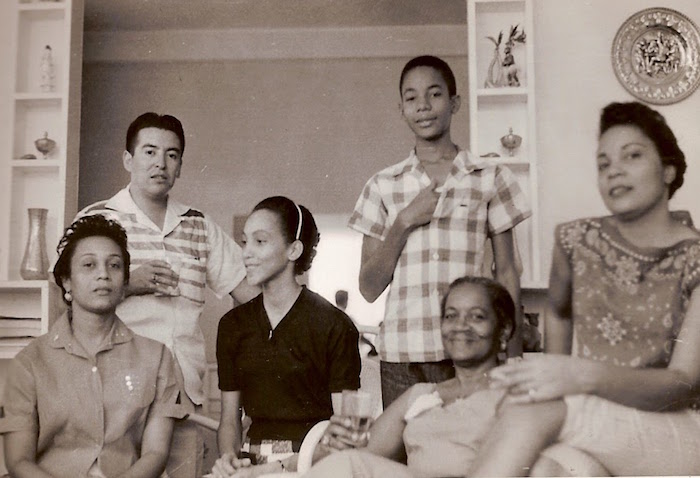

We had briefly shared this world—between 1994, when I was born, and 1998, when she died—though we never met, because she lived in Panama and I in Brooklyn. But I had seen photos of her: mostly sepia-toned images of a dark-skinned, white-haired woman with glasses, a nose like my father’s, and a graceful neck that made her the center of each picture. There was one photo in vivid color taken just a few years before her passing, in Coronado, Panama. She sat on a chair surrounded by our family, wearing a red dress patterned with white flowers, her hands folded on her lap.

When Ganny died, my grandmother went to Panama for the funeral, and on her return to New York, brought me back a purple stuffed beaver named Benny that she said Ganny had gotten for me. And though it wasn’t possible—though Ganny and I no longer occupied the same world—I believed her, and treasured the beaver like an intimate conversation between me and my great-grandmother.

As I’ve gotten older, however, the new details I learn of Ganny’s life seem to place her, and our family, into larger orbits of history. Ganny was born in 1900 on a wide swath of US territory, a banana plantation, on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. Its proprietor, the United Fruit Company, had been officially founded just a year earlier in 1899, through a company merger in Boston. United Fruit owned massive expanses of land stretching across several countries in Central America and the Caribbean, and Ganny’s parents had migrated to one of them from St. Lucia as part of a wave of West Indians gone to work for, as Gabriel García Márquez called it, the Banana Company. Ganny’s father was a carpenter whose labor was likely tied to the Church, and particularly to a white St. Lucian priest who ministered to the West Indian migrants. Ganny’s father, we believe, followed the priest from island to isthmus to island—St. Lucia to Puerto Limón to Bocas del Toro, Panama. Our family doesn’t know for sure; what record we have of these migrations lived in Ganny’s memory, not on paper.1

But plantation gets stuck on my tongue. What did a Central American plantation owned and operated by white men from the United States look, sound, and feel like? Because Ganny was born but not raised on United Fruit, I wonder about the conditions of birth there; about midwives, or about the possibility of friends come to help with the baby. The photos I’ve seen of the plantations from company archives do not tell me much about these conditions. They mostly document labor, though with little attention to laborers: dense rows of banana trees abundant with fruit, wholly cleared dirt pathways dividing those rows, thatched-roof buildings that mark “engineers’ quarters” or “overseer’s quarters.” Even when workers are present in these photos, the captions begin with verbs, not people: “planting banana bits” and “bringing fruit to loading platform.”2

When Black workers’ faces are caught by the camera, it seems almost accidental, like the result of a last-second glance at the photographer. Looking at these photos, I crave a return to the intimate, those small glimpses of a life that might give my memory a place to land. That might restore someone like these workers, or like Ganny, as the primary subject of an imperial archive. I also think about the US South, and what it meant that, across national borders, slavery was over and yet Black people continued to live and labor on plantations.

From Limón and Santiago de Cuba to Mississippi and the Carolinas, Black families had experienced just a generation’s respite from the wide reach of plantation work before racial capitalism created new iterations of itself. Indeed, the boundaries of the Global South have often, in practice, been drawn not so much around national lines, but around the “everywhere that Black people [call] home.” Everywhere the Global North has extracted air to supply its own breath.3

And I am captured by Ganny’s birth, or rather, the place in which it happened, because of the degree to which it predicts successive migrations, and inhabits a nexus between historical process and singular life. Perhaps a more honest way to phrase what I mean is that I am astounded to find my own family located so precisely within this particular and somewhat under-accounted-for period of Caribbean migration, neocolonial violence, and diaspora. As Christina Sharpe writes in In the Wake, Ganny’s patterns of migration linger in my mind as I attempt to “connect the social forces on a specific, particular family’s being in the wake to those of all Black people in the wake.” Like Sharpe, I too suspect that the geographical narrative of Ganny’s life might tell us something about national and racial identities within the afterlives of slavery and colonialism.4

These relationships—between family biography, migration, imperialism, land theft, and labor—seem to form something both nonlinear and repeating, though not bound by the enclosure of a circle. To me, they represent the most American of stories. And also the Blackest of stories. The most Caribbean of stories. That is, American anti-Blackness has always been a hemispheric project, and so too have expressions of Black survival and regeneration. Those “small [paths we clear] through the wake.”5

Ganny’s life, and its bearing on my own—its arrangement of the planets under which I was born in Brooklyn, New York—asks that I think about Blackness in global terms. Indeed, just a couple of years after arriving on United Fruit in Costa Rica, Ganny’s family migrated once again, this time to Bocas del Toro, an island off the western coast of Panama. In three years, they had crossed through and inhabited at least three nations—four, if we might count corporate-owned land—without ever leaving the Caribbean Sea.

In Panama, as in Costa Rica, the United States made its nationhood anew via the repeating acts of geographic expansion, displacement, and “ingenuity” produced largely by Black and Indigenous exploited labor. Although Ganny’s family did not live on a banana plantation once in Panama, the United Fruit Company owned many of the plantations in Bocas as well, dispossessing the Indigenous Ngäbe of their land in order to grow and export monocrops. In Panama City, the US government followed France’s earlier attempts, operating at an even greater scale, to construct a canal connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, and in 1904 claimed the Panama Canal project, and the territory in which it would be built, for itself.

Ganny’s family, and others like them, though essential to nationalist projects of various empires, were themselves not so much making nations. As West Indian colonial subjects who had migrated to primarily Spanish-speaking countries, they were, in fact, routinely excluded from the concept. Instead, their communities were worldmaking: forming diasporic subjectivities through movement across multiple Souths, and through reliance on each other in navigating these spaces. Ganny did not spend her childhood in Limón, but in what we might consider its kin. Bocas del Toro was about two hundred miles away, and a similar site on that Caribbean circuit traveled by Black folks pulled toward or coerced into manual work.6

If West Indian migrants were participants in and architects of diaspora, then they directed many of their engineering efforts toward transnational political thought and struggle. In the early twentieth century, Panama was a center of Garveyism, the pan-African Black internationalist movement led by Marcus Garvey. By the time Ganny reached adulthood and left Bocas for Colón, the bustling, majority-Black port city on the Atlantic side of the US Canal Zone, there were forty-seven chapters of the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the country. Back in Bocas, West Indian laborers working on United Fruit plantations avidly consumed Garvey’s Negro World newspaper, which was based in Harlem, as well as other periodicals from African American presses in the United States.7

Such cross-border exchanges suggest that we understand Black cultural and social movements not as tied exclusively, or even mostly, to the nation-states or colonies in which they form, but to each other. Those understandings of history that insist on ethnic, linguistic, and national distinction in the formation of Black movements belie the extent to which those movements have found nourishment in hemispheric (and global) contexts.8

Indeed, in the Panama Canal Zone, where Ganny found work after moving to Colón, evidence of both transnational anti-Blackness and Black diasporic interdependence was especially clear. Ganny had originally relocated to Colón with her younger brother and a childhood friend, whom my father calls her “hermana de crianza.” Through this hermana’s connections, Ganny found a place to live—a house made of concrete rather than wood—that granted her a level of privilege relative to many of her peers. But like many other West Indian women, Ganny also worked as a laundress in the Canal Zone washing clothes for white American families. By her midtwenties, she was a single mother of three, recently left by a Jamaican husband fifteen years her senior who had immigrated to Panama and then quickly returned home.

The Zone was organized by its own articulation of de jure racial segregation, the Gold and Silver Roll. The West Indian workers contracted to perform the bulk of labor in constructing the canal were paid less than their white, US citizen counterparts, and in silver. Silver and gold designated which houses employees could live in, what parts of a hospital they could access, which water fountains they could use. This apartheid was gendered too, shaping the nature of Ganny’s labor. Most Black women in the Zone worked in either laundry or as domestics in the homes of white Zonians, and interacted most often with white American women who held complex and varying degrees of power in relation to them.9

It’s a kind of segregation familiar to many of us in the United States. But this system was not merely a translated version of Jim Crow; established by the same government, the two systems developed almost simultaneously. And in the 1960s, when the Civil Rights Movement gained ground in the United States, the wins were felt in the Canal Zone too.

Our diaspora is linked in part by a history of slavery, but also by all of the ways slavery’s underlying logics have formed the conditions in which we have lived since. Sigue la memoria de la esclavitud, sigue la memoria de sus restos. We find it in the racial hierarchies that continue to structure our lives. In the push and pull of labor opportunities that lead to dangerous and unfairly compensated work on transcontinental railroads, canals, and fruit plantations. In what documentation exists of the past, and of our ancestors—in who gets remembered, and how. In the Souths made around us, and the Souths we make; shared experiences of subjugation shape our identities, which in turn facilitate the ways in which we share our resistance.

Kim D. Butler’s work on diaspora theory helps elucidate some of these ideas. In “Defining Diaspora, Refining a Discourse,” Butler clarifies diaspora as a category analytic, a theory that can be applied across groups. She emphasizes several of its defining aspects, including a process of dispersal, a relationship to homeland and to hostland, and an awareness of group identity as a diaspora. For a diaspora to be a diaspora, communities must understand themselves as belonging to one another. It requires a recognition of transnational kinship.10

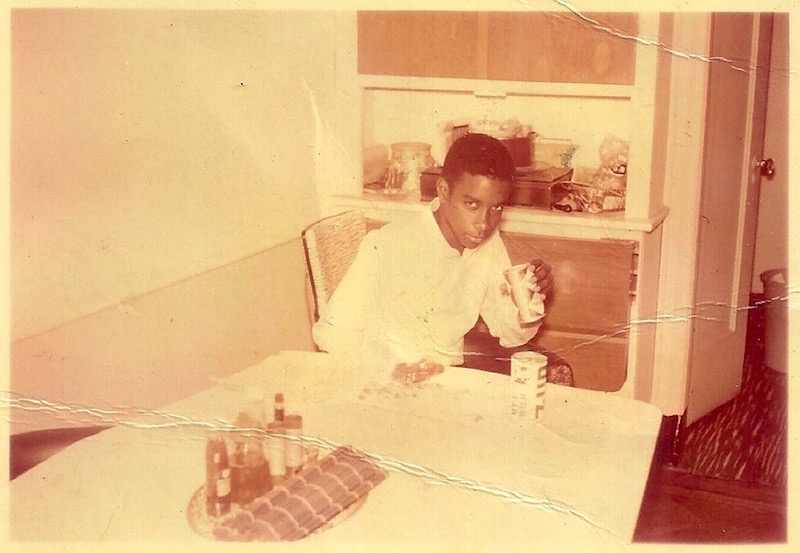

My father, Ganny’s second-youngest grandchild, began to occupy this kind of belonging once he immigrated to the United States. He arrived in New York City in 1968, a few years after Ganny did. In what would be her penultimate migration, she had relocated to the States in her sixties to work as a home caregiver for elderly white folks, hoping to earn enough to buy a house for her and her daughters back in Panama. But Ganny lived in Brooklyn, and my father in the South Bronx with his parents. And just a few months after beginning the eighth grade, Papi started to learn about both the emerging Black Power movement in the States and the ongoing Panamanian struggle against US control of the Canal Zone.

Papi found magazines in the back of his father’s closet documenting the Panamanian fight for sovereignty, and he interpreted what he learned through the lens of a Black Power politic. That is, he saw that both mobilizations were connected, or could be. For him, a Black immigrant teenager whose life had already been so clearly shaped by empire, it seemed intuitive that imperialism and anti-Blackness relied on each other. At school, he started refusing to say the Pledge of Allegiance and argued with his teachers in the English he was still learning to use. Although just thirteen and still forming his political consciousness, my father seemed to understand himself as a part of a diaspora, and as necessarily in solidarity with Black kin in the US, and Black and Brown kin in Panama. His was a view that fundamentally opposed domination—and not merely its local manifestations.11

So what do we do with specificity? With distinctions between Black communities across nations? We have words for other possibilities of being: rejecting universalism, we might position ourselves as a collective looking out toward the world, while grounding ourselves in our specific landscapes. We don’t need to collapse difference to imagine ourselves into community, or to draw from the historical networks that have nurtured so many of our movements. We can contend with complex arrangements of power that wield themselves vertically even within horizontal relationships. In fact, we might use diaspora as a tool for troubling sameness and honoring particular geographies of Black identity, while practicing our commitments to each other.12

But there’s something else here—a tension between family story and historical record. The thing that implores me to rifle through old photos and imagine conversations with ancestors. This notion that our stories perhaps offer one of the more effective means through which we can capture our multiplicity, or what Paul Gilroy calls our “changing same.” That is, we should pay attention to the ways in which continental histories imprint themselves on intimate lives.13

Ganny didn’t know she had been born in Costa Rica until she was sixty years old, living in Panama City, and she applied for a passport for the move to New York. It was then that she learned she wasn’t a Panamanian citizen at all. And that her birth name wasn’t Lydia Andrews, as she had always known it to be, but Fortunée André. Both names nodded to the French-British competition for colonial control of St. Lucia during the seventeenth century.14

This story is both hers and not hers, mine and not mine. My father made these discoveries about Ganny in 1988 one afternoon in Panama during the rainy season, while he and my pregnant mother visited her at the house she had finally bought for her daughters and her to live in. Papi had asked to interview Ganny about her life, and the two of them sat down together at the table facing her yard, where she grew both bananas and their cousin, plantains. Five months later, when my older brother was born, my parents made André his middle name, after Ganny.

In these details alone, we find an abundance of both memory and its absence—how is it that my great-grandmother didn’t know where she was born? Didn’t know she wasn’t a citizen of the country in which she lived? These threads pull us back to contested empire, to lifetimes of successive migration—the “exodus” of Bob Marley’s Exodus people—to family silence, and to the precarious citizenship that marks the experiences of so many migrants (and certainly of West Indian migrants in Panama). Family history allows us to peek in through the windows to see how larger forces enact themselves in small ways. What does empire look like on our skin? How does slavery’s afterlife sound in our names? What homes do these make in us?15

We might navigate these questions by approaching our family history alongside and within the archive, observing the points of tension at which we—descendants and archive—make competing claims for what we might call our own. Here our work must rest on that stretch of space between the private and the public, those intimate annunciations where we witness the public stake its power. In attempting to track Ganny’s migrations, in trying to recover her relationship to the place in which she was born, I attempt to make a “reckoning of movement,” understanding that although, as Hazel V. Carby writes in Imperial Intimacies, “the story of imperial relations is as restless as the Atlantic … it is also anchored, temporarily, in the particular places in which people in my family lived and died.”16

This process of intimate retrieval and return—where we recognize singular life within historical sweep, and simultaneously reopen space for the sweep, for what doesn’t feel so familiar—helps us to make sense of scale. Because the nature of diaspora, the nature of our Souths, seems necessarily to rely on and collapse distance: geographic, affective, familial. But when we regard that distance with restraint, we can, even just for a few moments, hold on to the specificity of the people and places we come from. Such specificity is part of how we trace our “small paths through the wake,” part of how we document our living, as Christina Sharpe writes.17

I think of Ganny’s red and white patterned dress in that photo. Of the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren at her side. I think of the light there, a soft afternoon light I associate only with summer, but that in Panama’s countryside may have also been winter. I think of the street where Ganny lived, for some years, in Brooklyn. In a neighborhood that for a few decades remade its landscape in the image of West Indian and Puerto Rican immigrants. These folks rented rooms, not apartments, and spoke several languages. The colonial ones—English, Spanish, French—and the remixed creations that narrated other kinds of survival through the former: Haitian Kreyol, several kinds of Caribbean Patois, Nuyorican Spanglish.

I think of that brownstone on Lincoln Street where Ganny had a room, and how close it was, just a short walk, to the street on which I was born, a few blocks shy of Flatbush Avenue, nearly half a century later. I think of the elasticity of time between the lives she and I both lived in that place. We belong to history, yes, but mostly to each other.

This essay first appeared in the Imaginary South issue (vol. 26, no. 4: Winter 2020).

Maya Doig-Acuña is a Brooklyn-born-and-raised writer, scholar, and doula-in-training. She has been published in Remezcla, Latino Rebels, Guernica, and elsewhere. She is currently a doctoral student at Harvard University, researching and writing about Afro-Panamanian migration, community, and memory within a context of Black diaspora.

Header image: Photo detail from the United Fruit Company plantation near La Lima, Honduras, August 31, 1954. Photograph from Associated Press.NOTES

- Ronald N. Harpelle, “Bananas and Business: West Indians and United Fruit in Costa Rica,” Race & Class 42, no. 1 (July 2000): 57–72; Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, trans. Gregory Rabassa (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006).

- “United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, 1891–1962 (inclusive), 1920–1960 (bulk),” 1891, Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard University.

- Avi Chomsky, “Afro-Jamaican Traditions and Labor Organizing on United Fruit Company Plantations in Costa Rica, 1910,” Journal of Social History 28, no. 4 (Summer 1995): 837–55; Ian D. Ochiltree, “‘A Just and Self-Respecting System’?: Black Independence, Sharecropping, and Paternalistic Relations in the American South and South Africa,” Agricultural History 72, no. 2 (April 1998): 352–80; Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson, Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018); Jarvis C. McInnis, “A Corporate Plantation Reading Public: Labor, Literacy, and Diaspora in the Global Black South,” American Literature 91, no. 3 (September 2019): 523–55; Alán Pelaez-Lopez (@MigrantScribble), “When talking about the ‘Global South’ we have to remember that East Oakland is part of the ‘Global South,’ Ferguson is part of the ‘Global South,’ the Bronx is part of the ‘Global South,’ Native American reservations are part of the ‘Global South,’” Twitter, July 24, 2019, 7:03 p.m., https://twitter.com/MigrantScribble/status/1154165349794766848.

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 8; Saidiya V. Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route, 1st ed. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007).

- Juliet Hooker, Theorizing Race in the Americas: Douglas, Sarmiento, Du Bois, and Vasconcelos (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); Sharpe, In the Wake, 4.

- Kaysha Corinealdi, “Creating Afro-Diasporic Solidarities from Panama to the United States,” (lecture, Afro-Latin American Research Institute Colloquium, Cambridge, MA, April 1, 2020); Hunter and Robinson, Chocolate Cities.

- Olive Senior, Dying to Better Themselves: West Indians and the Building of the Panama Canal (Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 2014); Ronald N. Harpelle, “Radicalism and Accommodation: Garveyism in a United Fruit Company Enclave,” Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research 6, no. 1 (2000): 1–28; McInnis, “A Corporate Plantation Reading Public.”

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Velma Newton, The Silver Men: West Indian Labour Migration to Panama, 1850–1914 (Kingston, Jamaica: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies, 1984); Julie Greene, The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal (Penguin: New York, 2009); Joan Victoria Flores Villalobos, “West Indian Women in the Panama Canal Zone, 1904–1914” (bachelor’s thesis, Amherst College, 2010), https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00019230/00001.

- Kim D. Butler, “Defining Diaspora, Refining a Discourse,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 10, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 189–219.

- Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton University Press, 2019).

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

- Gilroy, Black Atlantic, 122.

- Aonghas St-Hilaire, “Postcolonialism, Identity, and the French Language in St. Lucia,” New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids (NWIG) 81, no. 1–2 (January 2007): 55–77.

- I borrow this reference to Bob Marley’s album Exodus, in connection with West Indian migration in and out of Central America, from my godfather, Humberto Brown.

- Hazel V. Carby, Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands (New York: Verso, 2019), 18.

- Sharpe, In the Wake.