Our foraging friends on Occohannock Neck, Malcolm and Carol, assured us that there was a summer moment in which field corn achieved perfection for the plate—and then as quickly reverted to the unpalatable starches desired for animal feed. To prove their assertion, they invited us for a supper anchored with cold smoked venison, grilled fish, garden greens, and homemade pickles—all centered on the presentation of corn plucked hot from a dip in boiling salted water.

“Tomorrow,” Malcolm observed, “field corn will be inedible—unless you’re a chicken.”

“I wouldn’t wonder,” Carol footnoted, “if it wasn’t already past its moment this evening and already gone to starch.”

I paused mid-bite and asked the obvious. “How do you know the day—the one day of summer—has dawned when field corn is fit for the plate? Is it the color of the silk? Or something you see when you peel back the husk?”

“No,” Malcolm and Carol chorused, “it’s the scent of corn, how it smells early in the morning,” adding, “And you’ve got to be fast. It turns quickly.” He paused. “Plus, it’s not our field.”

For those who might not know, the difference between field corn and sweet corn is significant. Noah Hultgren of the Minnesota Corn Growers Association (admittedly far removed from the South) gets to the point. “Field corn,” he states with authority, “is used to feed livestock, make the renewable fuel ethanol and thousands of other bio-based products like carpet, make-up, or aspirin.” “Sweet corn,” on the other hand, “is harvested when the kernels are soft and sweet, making it ideal for eating.” Then he gets to the culinary punchline: “If you grab an ear of field corn and try to take a bite, you’ll probably break your teeth. It’s hard and dry (and only tastes good to cows, chickens, pigs, turkeys and some wild animals).” David Shields, author of Southern Provisions, deepens the explanation with his customary erudition: “Sweet corn came about as a mutation to the mechanisms that convert sugar to starch as part of the maturation process in field corn, interrupting the conversion and rendering the kernels sugary rather than mealy. Three ancient strains of sweet corn—chulpi in South America, mais dulce in Central America, and popoon corn in North America—were cultivated by Native peoples, harvested green and eaten as a vegetable rather than dried down for grinding into meal.”1

“If you grab an ear of field corn and try to take a bite, you’ll probably break your teeth.”

In mid-summer on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, field corn grows tall and dense. Sweet corn fields tend to be markedly shorter and more spindly in appearance. Malcolm and Carol, sensitive to the instant when the flavor and texture of field corn align with those of sweet corn, annually seize their opportunity. I happily bite into my purloined ear of corn with the conviction that it’s generally a good idea to eat the evidence—at least when it comes to corn.

My thoughts wandered to the scent of corn and an August afternoon a lifetime ago in the company of my friend and fabled local antiquarian Ms. Jean. The redolence of corn in scorching summer perfumes the imagination, flavors recollection—and there’s plenty of corn and memory to go around in our corner of the world.

Ms. Jean wedged a note folded into the doorjamb of the house I rented in the crossroads village of Eastville Station where the station part of the equation disappeared years and years ago. “Remember those baskets I told you about?” her neat, handwritten message queried and then commanded. “Be at my house at 1:00 tomorrow and be prepared.” This was an invitation that could not be declined, and I went.

The dog days of August on the Eastern Shore of Virginia can test the bounds of human hope and endurance. The breezes go still, humidity populates the roads with optic distortions that appear as giant black snakes rippling from a verge of browning grass and then evaporating into the radiant heat. Cicadas scream their songs of lust and death. As the day cooks, the sky goes from an anemic blue to cloudless white. You can scarcely catch your breath—and when you do, the air tastes of hot sand and sour dust. Those who work the tides sweat even standing in water and reflective light so vivid that the color washes out of their eyes. When thunderstorms roll through, relief is illusory—the heavy showers feed the wet air until it hangs as heavy as sodden drapery. Still, it could always be worse.

I pulled into Ms. Jean’s shell drive, parking in the pitiful shade cast by a recently planted, somewhat wilted sapling. Ms. Jean, who never wilted even on the hottest days, stepped from the house in her light cotton print dress, hair pulled back, and, smiling as always, greeted me as she descended the porch steps. “There you are, you rascal, you’re on time! Let’s get going!” Ms. Jean didn’t fritter away time with idle chatter. We were on a mission and it was time to get on down the road in her old station wagon and on to our basket destination. Apparently, a clock somewhere was ticking. Fortunately, the drive to Edward Wyard’s Farm wasn’t a long one.2

Ms. Jean pulled into a sandy farm lane and stopped the car. The breeze generated by our passage died and summer heat poured through the open windows along with a few mosquitos and a ravenously vicious greenhead fly. The insects went right for me, ignoring Ms. Jean as if they knew better. I felt sweat beading in the small of my back. “Now,” she cautioned, “whatever you see, don’t act surprised. I can’t say more, but you’re a reasonably bright boy, and you’ll figure it out soon enough.” This sounded like a lot more than baskets were on the docket, and I promised to be on my politest, most circumspect, go-with-the-flow behavior. Good enough.

The farm lane, bright white in the unrelieved sunlight, with a comb of undercarriage bruised and blackened grass up the middle, ran in an arrow-straight line to a dark spot of distant shade where Mr. Wyard lived in the old family house. Acres of ripening field corn towered above the car on either side, their perfumed and fecund scent overpowering the senses. The sensory implications of that afternoon with Ms. Jean was the day Malcolm and Carol were trying to explain over dinner, but my thoughts were far away and saturated with the rich smell of corn on its single day of culinary achievement. The corn—all ringed and jointed stalks, sibilant leaves, greenish-blond silk going brunette—teased the senses with transient pleasure. We drove forward, the dark oasis of farmhouse, barns, and trees slowly heaving into focus. Startled quail erupted from the grass in front of us, fluttering and running for sanctuary.

The corn—all ringed and jointed stalks, sibilant leaves, greenish-blond silk going brunette—teased the senses with transient pleasure.

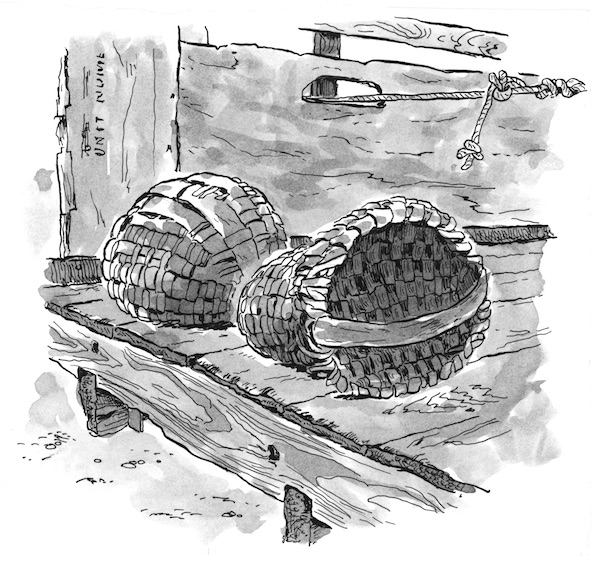

Ms. Jean pulled into the yard, stopping next to an ancient farm truck with plywood sides and floor. Mr. Wyard, thoughtfully, had arrayed three old baskets on the truck bed. Woven from hand-riven splints, the baskets presented the hallmarks of the locality. Almost perfectly hemispherical, each one consisted of ribs so broad that the weaving splints could scarcely pass between them. A loose knot joined the rim to the handle and the central keel-like rib. Years of use had buffed the interior surfaces and abraded the exterior, fully exposing the baskets’ architecture. In the world of basketry, these objects were special only by virtue of their structural idiosyncrasies and visually and tactilely palpable work histories. “Those are the baskets,” Ms. Jean noted. “Now follow me.”

We crossed the turnaround, entering the deeper shade of the trees and the kind of incremental coolness gently laving leaves evoke. We climbed the steps of the porch that ran across the front of the house, walked up to the screen door, knocked, and stepped back down to the ground, waiting. We could hear scuffling footsteps inside the house and a voice call out, “Come on up!” Back on the porch, we could see the tall, lean figure of a hatted man, all shadow and silhouette, moving down the hall toward us. A breeze ran through the house, brushing our faces as the figure came forward. “It’s Jean, Mr. Wyard.”

“Miss Jean,” he responded, “you’ve come to see about those baskets, I imagine.”

“Indeed, I have,” she replied, “and I’ve brought my young friend along. He’s interested in all the old things.”

“Well, then, come in and have something cool to drink,” he invited, pushing the door open and lifting his big straw hat in a gesture of good manners.

Mr. Wyard was as bald as every cliché in the book—egg, billiard ball, baby’s bottom—except that he had addressed the absence of hair by painting his head with stove black. He’d done a neat job of it, too, smoothing the black and combing it in such a manner that in the dim interior light he’d created the illusion of thinning, lank strands. The artfully drawn part that ran from crown to forehead added to the overall effect. As Mr. Wyard pivoted to pour us ice water, Ms. Jean shot me a cautionary look. I absorbed the old family photolithographs on the walls, took in the early-twentieth-century parlor suite, sipped the cold drink in my hand, watching condensation slip down the sides as sweat continued to drool down my back and prickle on my arms. Ms. Jean and Mr. Wyard chatted. She was cool in her summer dress; he was cool with his precisely delineated head of painted hair.

Ms. Jean and Mr. Wyard chatted. She was cool in her summer dress; he was cool with his precisely delineated head of painted hair.

The scorching afternoon inched toward the cooler hours of the day. Mr. Wyard looked up and observed that it was time to get back to work. Ms. Jean agreed, and I simply nodded. We left the parlor, walked down the hall where a mirror hung just inside the door, crossed the porch, and stepped out into the yard. The promise of a storm was lifting on the southwest horizon, just visible above the corn. Mr. Wyard, rehatted, accompanied us out to the car and then stopped. He leaned toward Ms. Jean, “You came all the way out here to see those baskets, you might as well have one.”

“You, too,” he extended the offer. “You seem to care for the old things.” I took a photograph of the baskets in the truck and then, after Ms. Jean had made her selection, chose one for myself. I have my basket, still.

Back in the car, down the lane. The shoosh of sand beneath the wheels, the crinkling cackle of corn in our ears as a breeze stirred, we drove to the edge of the hard surface road and Ms. Jean stopped the car. “What,” she quizzed, “did you make of that?”

“I’m not altogether sure,” I answered.

“Well,” she paused as the car idled and the scent of softened road tar and corn on that one day of the summer wafted around us, “I’ll tell you now.” She looked me in the eye, “Vanity is a wonderful thing.”

She hit the gas. I looked at my basket with new appreciation.

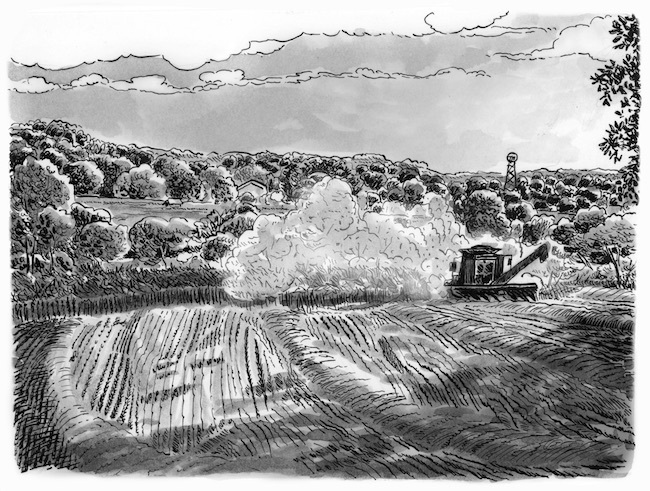

Carol and Malcolm are right. The field corn purloined on that one summer day is perfect. They say they smelled it in the offing and I am convinced. Chomping down on the ear, I sense the milky sweet scent of corn reminding me of the lane leading to Mr. Wyard’s house. Tomorrow the field corn will taste of the coming harvest season when the big combines drive through the skeletal stalks mowing the dried corn now fit only for animal feed. Some growers are careful to waste enough on the ground to attract migrating Canada geese into shotgun range when the hunting season opens. Soon enough. November and the stubble fields crawl away to black lines of pine and a sulking sky that will be winter.

Bernard L. Herman, George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies and Folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, works on the material cultures of everyday life and the ways in which people furnish, inhabit, communicate, and understand the worlds of things. His teaching and research cohere around teaching and public engagement and a deeply held belief that work of the arts and humanities finds its first calling in the public sphere. He also grows oysters on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, where he cultivates a “library” of fig varietals.