Representations of older transgender people are nearly absent from our culture and those that do exist are often one-dimensional. For more than five years, we traveled throughout the United States creating To Survive on This Shore: Photographs and Interviews with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults, which culminated in a fine art exhibition and book about the lives of older transgender Americans. Here, we share portraits and interview excerpts with participants from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Missouri, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., to highlight the ways in which transgender people are aging in the South. Our participants’ experiences reflect the complex intersections of gender identity, age, race, ethnicity, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and geographic place. Their narratives of growing older illuminate a diversity of lived experience, varied approaches to aging, and, in many cases, they also point to contradictions in southern culture. While the South is often characterized as promoting exclusionary norms and policies toward gender and sexual minorities, it also celebrates southern affinity and local familial and community ties in ways that promote support for some trans people. In this regard, many of the participants in this project shared experiences of both social marginalization and receiving love and support from their families and communities. We hope these portraits and narratives provide a nuanced and complex view into the struggles and joys of growing older as a transgender person in the South, and inspire reflection on what it means to live authentically in later life.

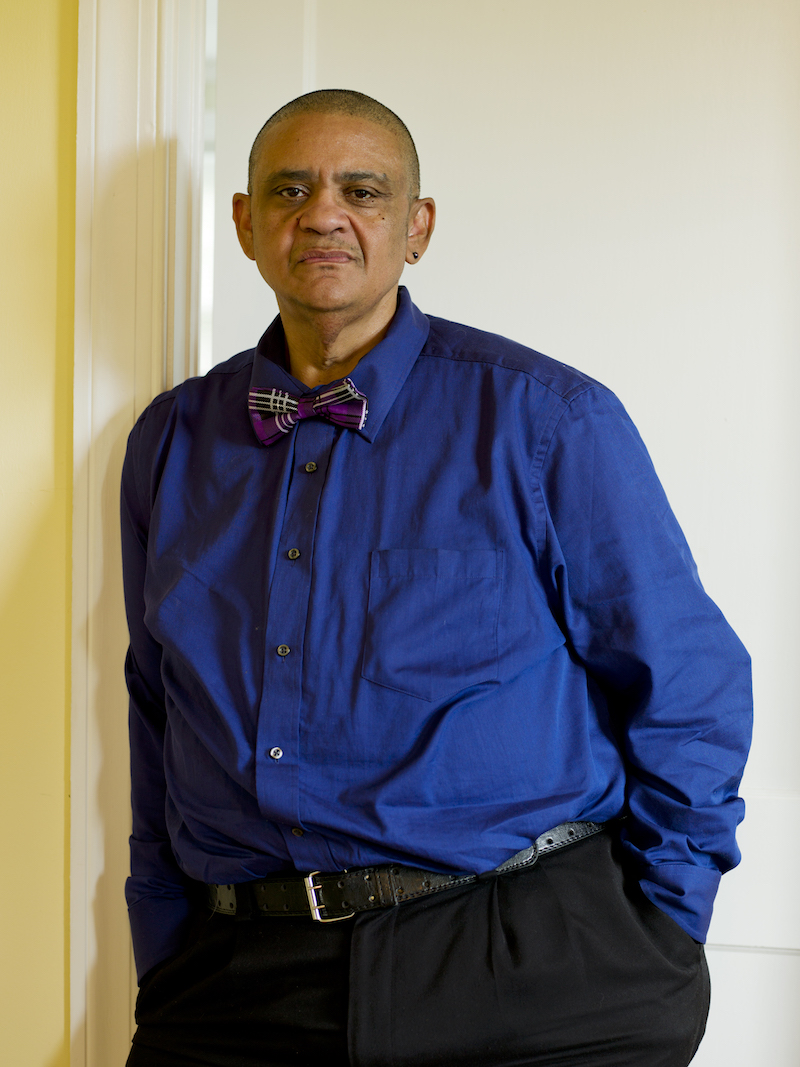

Monica, 62, Baltimore, Maryland, 2016.

When I was four years old, I tried to tell my mother I was a girl. It was 1957. It went over her head. I told her, “Mother, I think I’m like Rosemary Clooney.” She said, “Child, you can’t be like Rosemary, Rosemary’s white!” And so I never thought that she understood. Now looking back at it, there are a lot of things in my life that give me clues that maybe she did understand and did what she could in her own way. My mother died before I transitioned, but when I came out to my aunt she told me she had had conversations with my mother, but back then, in 1955, they didn’t have the language. By the time I had a conversation with a professional, I was an adult. This doctor asked me if I was “truly” trans. And my response was, “Why are you asking me that? Because I don’t fit some criteria in your book?” It bothered me that somebody who wasn’t trans had criteria for someone who is trans, to measure my transness. All I knew was that I had a sense of myself, and it was based on my lived reality.

I struggled with drugs and alcohol for years, and kept abandoning but then coming back to this part of myself. In 2002, I had a heart attack and almost died. I was three years clean by then and started having this recurring dream. In this dream, there was this big booming voice, like the voice of God, and it said, “If that’s who you’ve believed you are your whole life, then why did you lie to everybody your whole life? Why did you continue to deceive everybody and why continue to deny yourself?” The first night, I shook it off, it was just a dream. But then I had the same dream the second night, and it disturbed the hell out of me. When I had it the third night, I just couldn’t believe I kept having the same dream. There was something about it that gnawed at me, something very real. And I couldn’t shake it.

When I told people about the heart attack, the only thing I could tell them was that there was something in me that knew I was dying. Right after, I wrote a poem called “One Minute,” because I remember asking God for one more minute. And I felt like the rest of my life was about, “What am I going to do with one more minute?” At some point, I don’t remember what day, I just made the decision that I couldn’t lie anymore, and if I was going to die, at least I needed to know who I was.

“What am I going to do with one more minute?”

When I finally came out to my father, I went over to see him and he said, “This is a shock, but on the other hand I guess I’m not really surprised.” What he was more interested in was if I was still drug- and alcohol-free. And then he wanted to know if I still loved baseball and football, because we were a baseball and football family. Then, we had conversations that reminded me that I come from a family of activists, and that’s something that over the years has helped me to get a deeper realization of who I am and where I come from. My family came up here during the migration. My grandmother was homeschooled and well educated. And my great-grandmother came from slavery, so they were radical as well, because they had to hide books in order to be able to read. They passed that strength down through the family, and they passed it down to me.

Charley, 53, Charlottesville, Virginia, 2014.

I’ve lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, all my life. I identify as male, and I’ve been on hormones now for almost three years. I lived as a male before the hormones for a year. I’ve struggled all my life with my identity, and was working with a therapist, and finally realized what was going on, and decided that the only way that I was going to be truly happy was to be able to transition. I’ve also been in recovery from drugs and alcohol. I’ll pick up an eight-year medallion on May 22. So that’s a major accomplishment in my life.

I think the hardest part was—and still is—trying to get my family to accept [my transition]. They still use the female pronouns. And I don’t think I’ll ever get them to that point. A few years ago, that would have really bothered me, that they have not accepted it. But I’ve got to realize that they’re on their own path, whatever path they’re on, and I’m on mine.

In the beginning, when I started transitioning, when my features started changing, when it got to the point where I was totally male, I wondered why people were treating me differently. Other races were treating me differently. And I realized, I’m a black male now, and so when I step on the elevator, the woman’s going to clutch her pocketbook, or she’s going to move to the other side of the elevator, or I get doors slammed in my face. You know?

But I will say that being a male—not so much just because I’m a black male, but being a male—I believe I have gotten better jobs because of being a male. Because I don’t have to sit across that table with somebody interviewing me as a butch lesbian, and they’re trying to figure out, “OK, is this a male? Is this a female? Do we want this person with this large question working for us?” But I have gotten more jobs and, as time goes on, better jobs because of being a male. I really believe that.

Going to therapy was probably one of the most freeing things that ever happened in my life. And transitioning at fifty probably saved my life. Because at the rate I was going, I was going to start drinking again, and if I started drinking again, I was probably going to hurt myself. That was the way I drank. I was so miserable being inside this body. I had not been able to hold down a relationship because I was such an angry person. I had a lot of anger issues. I had a lot of self-esteem issues. My confidence level was very low. I had some intense therapy to really get to know who I was before I started into any of the transition. I am such a whole person now, for going through this. I’m more happy with life. I’m not dating anyone right now, but I know the next relationship that I go into, that person’s going to be damn lucky. Because I’ve got my shit together. I’ve got my game on.

I’m not dating anyone right now, but I know the next relationship that I go into, that person’s going to be damn lucky. Because I’ve got my shit together. I’ve got my game on.

SueZie, 51, and Cheryl, 55, Valrico, Florida, 2015.

SUEZIE: I never thought transition would be a reality in my lifetime. After struggling for years, I finally asked Cheryl, “What about surgery?” And she looked at me and said, “Go for it.” Finally, she had realized how serious I was. Every night I used to sit in the lanai smoking away, and just thinking, “Can I do it? Can I not? Can I do it? Can I not?” Every night. For years. I also had bad asthma, copd, sleep apnea, acid reflux, migraines, you name it. But when I started going through the motions everything pretty much vanished overnight. All those illnesses, all those stresses, gone. I said to Cheryl that I felt so good I could probably give up smoking and I wouldn’t even notice. Didn’t have another one [cigarette].

Years of self-administering hormones caused a complication that threatened my chances for surgery. I said to Cheryl, “I’ll die as female. Nothing is stopping that surgery.” If there was a 95% chance of failure, of dying on the operating table, that was a risk I was willing to take. I could not go on how I was. My greatest challenge, it came from within. It was having the confidence to face the world out there. The perception that everyone isn’t going to accept you, it’s a little unfounded. When you first come out, you’re pretty rough. You get a few people to support you. Plenty that don’t. As you start looking better, people start changing their opinions, they swap sides. They join the winning side. And you start getting more supporters.

I don’t care what other people think. “Peripheral blurring,” that’s what I call it. I am aware but don’t pay attention to those negatives to my left and right; I only focus on the positive reactions ahead and in front. So now I go out, bold. I’m in the real high heels, and I have the striking hair. How I see it is, if you’re bold, it’s very positive. It’s not wishy-washy. When you’re positive, it builds your confidence, and of course confidence is attractive, and with attraction comes acceptance. That’s my theory on the whole thing. Bold first, stand out.

CHERYL: When we got married, I never imagined that someday my husband would become my wife. Right from the start, SueZie confided that she identified as female on the inside, but transition never appeared to be an option. But, I never had a problem with her wearing lingerie. You know, it’s just clothes. I fell in love with the person inside, and what’s on the outside is more about what they feel comfortable with. In 2009, when she said she wanted to transition, I admit I wasn’t very accepting. It was more like, “What’s going to happen to the kids and what are people going to think?” At that time we weren’t strong enough to risk losing everything, including each other.

I asked her when our son Jaison was born, “Are you even happy?” Because there was no emotion. After transition, it was a total 180. Her disposition improved and our life around here got better. I saw the difference in her and how much it really affected her. I had never seen happiness come out of her eyes before. It was truly amazing. It was difficult and a learning process because, for instance, I was always heterosexual, never a lesbian. We say I became a lesbian by attrition.

But everything was for the better and it’s working out OK. Even our intimacy has elevated. As I tell people, “I fell in love with the person, not the appendages.” I’ll always love her and we are always there for each other, deeply connected. Jaison has always known that she wears “girlie clothes,” as he calls them, so he’s good with it too. We’re doing well. The smiles. Never had smiles before. If you’ve seen the pictures of before, you could see the sadness, there was no light in the eyes, there was no smile on the face. Now you can’t stop it.

If you’ve seen the pictures of before, you could see the sadness, there was no light in the eyes, there was no smile on the face. Now you can’t stop it.

What am I looking forward to in the future? Maybe she’ll get a little quicker on her makeup in the morning! Gosh, the future. It’s a whole new way of life. We’ve had fourteen years now, and I hope we’ve got another fourteen years ahead of us. I’m excited to see what the future’s going to hold, but also a little nervous. The unknown can be daunting, but we will face it together. I’m really looking forward to it.

John, 69, Mt. Ida, Arkansas, 2016.

I identify as male. And very binary, much more binary than I ever thought when I started this process. I grew up in the South. You didn’t even hear of it. When I was in college I went into an extreme depression, and I went to a psychologist who gave me a test that took about three hours. And they went through that with me and the psychologist said, “I never seen anything like this.” So, I saw him once or twice a week for the rest of the year, and at the end of the year, he said, “You have a male mind and personality in a female body.” He said, “I think it’s innate. I don’t think you will be able to change it. And it’s going to make your life difficult and you need to be aware of this.”

I feel very lucky that he gave me that bit of information because it could explain to me why I didn’t fit in the world. And I never did. I was great with working with people as a job. I was a great social worker. I did children’s protective work. But personally, one-on-one, I just never fit. I used to say all the time, “It’s like everybody got an instruction book to life and I didn’t get one.” You know, everything was so easy for other people.

Just sitting down and talking wouldn’t work for me. I had to work at it. I’d leave a situation and turn later to my daughter and ask, “Did I say the right thing? Did I sound OK? How was that?” Because it was always an illusion. I was always trying to be something I wasn’t and couldn’t be and so this went on until I was sixty-three. I woke up at 1:28 in the morning. I sat up in bed, and said, “I am transgender.” What is that? I had to go look it up on the internet. Then I realized there had been a program on TV a couple of weeks before and I didn’t think I was watching, but apparently, subconsciously, I was.

It’s like my life had been a scattered puzzle and suddenly the frame was there and everything fit and I understood the picture. I thought at that time that it was too late, as far as doing anything with my life. I have a bad heart valve, and I was 350 pounds, and my heart was failing. I’ve never heard of anyone my age losing one hundred pounds, much less two hundred. I had never heard of anybody my age transitioning. I couldn’t find anybody online. You know, I found people in their forties transitioning, but to transition at sixty-three!

It’s like my life had been a scattered puzzle and suddenly the frame was there and everything fit and I understood the picture.

When I am out there hiking, I have to look out for snakes. I’ve trained myself to watch three feet in front. And so I’ve learned to look closely now, and I see the most incredible things in the woods. The patterns and the leaves, the different leaves, the different mushrooms, the different insects. I didn’t know there were that many insects in the world! I give thanks for every single day. There is not a day that I am hiking and not thinking, “What a gift this is.” The woods change every day. There is always something new, and it’s exciting. So many people my age are giving up. They are slowing down. They are settling. But life for me is just still so exciting. There is still so much more to see and do and experience. And that’s what I want to do. I want to experience everything I can, as fully as I can.

Dee Dee Ngozi, 55, Atlanta, Georgia, 2016.

My middle name is Ngozi, which means God’s blessing. I was speaking on HIV and my journey with HIV in the church one night and this African minister just jumped up and said, “You’re Ngozi!” I said, “Uh, what do that mean?” and he said, “It means God’s blessing. You have God’s blessing.” So I adopted that name when I sent my name change in and then I had my last name changed to my husband’s and then we was married. I served collard greens, and ham hock, and baked cakes and he’s just as happy as a lark after the twenty-five years we’ve been together.

This coming into my real, real fullness of knowing why I was different is because I was expressing my spirit to this world. And I didn’t know how God felt about it but I believe in God and I have a deep spiritual background and I talk with the Holy Spirit constantly who’s taken me from the Lower West Side doing sex work to being at the White House.

We created the first trans ministry in our church and I sat on the “mother board” with the other mothers. One day, mother Gladys asked me to come and sit down there with them. And after we had our little meeting, after church, Miss Gladys went to do something in the office and then they surrounded me and said, “What gives you the right to be here on this mothers’ board? We don’t understand it.” I said, “Because I’m a mother to the ones you can’t love. The ones that you cannot be a mother to, that you throw out on the street every day. Those are my children. The ones you throw away.” I said, “That’s why I’m here.” You could hear a pin drop, nobody said nothing. They went on and accepted me and said, “Come on, girl, sit down.”

“Those are my children. The ones you throw away.” I said, “That’s why I’m here.”

I’d go to the clinic for my HIV, I would do stuff. I’d push patients, walk them to the car, sing church songs. I was just having a ball while I was waiting for my appointment. And a guy saw me one day that had an agency, and he said, “Miss Dee Dee, you work down here?” I said, “No.” He said, “I got a job for you.” And that was God just setting me in right there in that clinic with my own desk and I was my own boss. I could go to work as myself. The first day I got on the train with my little briefcase and my little suit on with the other people that were going to work. And when I got to the front door of the clinic, the Spirit stopped me and said, “Look across the street.” I said, “Look across the street?” So I looked. Then I saw flashes of me jumping in and out of cars on that corner, and I remembered I used to run girls off that corner. That was my corner. He said, “Now look how long it took for you to cross the street.” I could have lapsed right there on that sidewalk. This had come full circle now.

Hank, 76, and Samm, 67, North Little Rock, Arkansas, 2015.

SAMM: Hank didn’t know she was a girl until she was around eleven or twelve. She was always the boy in the family. If it was Thanksgiving, Mom and the girls cooked dinner while she and Dad went hunting. Her mother even customized her clothes. Every Easter, everybody got new blue jeans and yellow T-shirts. The girls got those blue jeans that zipped up the side, but Hank always got the fly front. The girls got a regular plain yellow T-shirt but Hank’s mother would create a pocket on hers so that it would be just like her dad’s.

HANK: But they didn’t call me “he” or “him,” they just called me Hank.

SAMM: They knew that Hank was different from her sisters and Hank’s dad was excited, I guess, about having this “boy,” and Hank’s mom didn’t object. Her father would put her in boxing matches with older boys and he was really proud. Once in a while some relatives would show up and say to her dad, “Hey, you are going to make that girl funny.” And Dick would tell them to mind their own business and leave Hank alone. And that was simply it.

HANK: It was a lot like in the olden days, you know, there were a lot of people around like me and people just expected us to become “unmarried aunts” or “fancy boys” and nobody ever confronted you with it. My father would say things like, “Oh, this one will never get married.” If I heard him say that today, I would say, “Oh, he’s telling them I am gay.” Only I didn’t have those words for it back then.

But when I was twelve, my parents decided that it was time for me to be a girl. This was a very strenuous thing for me because, of course, I didn’t want to be a girl. They started trying to work me into being a girl but by then my identity was already set. I was totally me. I always say, “I’m just Hank. I’m not he, I’m not she, I’m just Hank. I’m who I’ve always been.” But my father and mother decided that for my birthday they should give me some girl perfume. Perfume wasn’t something that I was familiar with. Of course, my sisters had perfume but that was for girls! And so, I was brokenhearted. I mean, they could have cut me with a knife and hurt me less than saying, “OK, now you are going to be like a girl.” Later on, when I was twenty-one, I went into the military, which took me away from them and everybody.

SAMM: But there were points in the military that were very difficult. She ended up being investigated for homosexuality and examined psychiatrically, and the army ended up putting it in writing that “while she had a pretty face, she was very masculine.”

HANK: I loved the military, but I thought there was no future there for me because of the stress of the investigation. I finally went to my superior and said, “Either you are going to stop the investigation on me or you are going to charge me on something, because I can’t go on like this.” It was a very traumatic experience for me.

SAMM: Eventually they brought it to a conclusion and they added up all of their evidence to find that they didn’t have a thing on her. Hank and I have been together forty-four years. We met after her time in the military, through some Chicago lesbians I had met. They threw a party every Friday night and, one of those nights, someone said, “There are some really fine dykes up in Western Michigan.” And then somebody said, “Road trip!” And thirty hours later, there we were in Kalamazoo. And so I found this one in Western Michigan. She was different from anybody I have ever met in my whole life and I knew that she would be in my life for the rest of my life. There was this immediate connection that would always be there. The way we are today, we started out that way.

Lee Anne, 64, McClellanville, South Carolina, 2016.

I was living in Wando, South Carolina, and one day at an environmental group meeting a friend told me she had someone she wanted me to meet. She introduced me to this petite southern schoolteacher who had never met a transgender person before. We sat down, we talked, we ate together, but then we went our separate ways. We didn’t exchange phone numbers, didn’t exchange addresses, nothing. Three days later, my phone rang. It was the school teacher, she’d tracked me down. About eight months later, we were married. Neither of us was looking and she considers herself to be a heterosexual. I consider myself to be a lesbian. But it works!

Unfortunately, I had to go back in the closet, because I had to get work. And so I went back into construction. That almost destroyed the marriage. I began drinking again, and overeating, and I was miserable. And I made her miserable. But the turning point came . . . Well, it took me three days to work up the courage. I had two drinks, and we sat on the edge of our pond, and I told her, “I can’t do this anymore. I cannot live this life. I cannot be like this anymore.” And I found a support group and started going, and I slowly started expressing myself more and more. Now we’re coming up on our nineteenth wedding anniversary.

I’m related to all the locals in our village. All the people who come from here, I am kin to them. My wife taught school here for over thirty years, so everybody knows her and loves her. She’s very well respected in the village. Would I have been as well received if I had not been married to her, or if I was not related to everybody? I don’t know. I am amazed that I have been accepted as well as I have. But are things going to change now that we’ve had an election that has empowered people to hate? I don’t know.

You have to have a thick skin to survive in the South being transgender. Unfortunately, I know too many who don’t. And most of them are young. I think that over the years, I’ve developed this thick skin because it’s either that or die. I actually considered suicide twice. I came very close both times. I remember one time when this feeling came over me that just said, “No. Be who you are.” And so I didn’t go through with it. I also find that I’ve become more empowered the older I get. You know those little memes on Facebook about the old people not giving a damn? Well, that’s basically how I am: “Accept me or get out of my way.” I’m not going to sit here and be silent for the rest of my life. What can you do to me that I didn’t already do to myself for most of my life? I beat myself down enough. I just want people not to give up hope. South Carolina’s state motto is, “While I breathe, I hope.” I used to think it was silly. I don’t anymore. I’m not going to give up hope. I’ve got to fight, and to fight, you have to have hope.

Diego, 59, Washington, D.C., 2016.

I have one of those kaleidoscopic identities. I identify as an openly transsexual man who’s Latino, who’s southern, and is a New Englander. I’m an immigrant. I was born in Germany and adopted as a baby. When I was adopted, I was the sickest child. My father, a decorated World War II veteran for the United States, as a Mexican American, told my mother that she could adopt a child but it had to be the one closest to death. For my mother, who was a concentration camp survivor, it really just meant that she got to bring back to life something that almost didn’t have that. I never had to struggle inside my family but only had to face external barriers. I always had a nest at home, and I realize that’s a privilege because not everyone has that safety at home.

My earliest memory of feeling like a boy was when I was two. I made up a name for myself, Diego Sanchez. Between age four and five, I realized that bodies were different because all my friends were little boys. I grew up in the Panama Canal Zone so kids were naked three-quarters of the time. We were getting in ponds or we were getting in creeks or we were getting in the ocean. It was always hot. So, I realized that our bodies were different, and it was distressing. I knew I was missing things. I told my parents at age five that I was born wrong. I told my mom first. My mother left the room and I thought, “I’m gonna get a whipping. It’s going to be a belt, it’s going be a wooden spoon.” She walked back in with a magazine, and it had a picture of Christine Jorgensen on the cover. And she said, “I don’t know if there are other people like you, who are born a girl and see themselves as a boy, but this woman was born a boy, grew up to be a man, and finally became herself, a woman. And I think that if it’s OK for her now, by the time you grow up it’ll be OK.”

In Latino culture, if everyone’s at home, the guys are hanging out. The women are doing a lot of the work and the men are being served. And somehow, since I was a kid, I was always granted that guy access by my uncles, aunts, and grandmother. I don’t know why. But I was always granted this place. At home, in the core nuclear status of my family, my mother taught me things that girls had to know, and my dad taught me things that guys needed to know. I was taught a lot of work and career and business and military things from my father that most daughters would not have been taught.

Having been raised as a Latina created a lot of expectations. As a Latina, you’re able to do certain things but you’re required to do others. And as a Latino, there are things you can’t do that you used to do, such as if somebody’s got a kid, and it’s cute, I can’t go over and say, “What a cute kid.” That’s true for most guys, but for guys of color it’s even more harsh. I am straight. I love women. I’m trying to learn to be more emotionally available. You have to be 100 percent emotionally there to expect someone else to be. I try to show love, whatever that is, but I try to find it and show it. As a Latino, I have to check myself because there are things that I expect in relationships. I honor women in ways that some women appreciate and some find demeaning. I will pull a chair, I will open a door, but it’s just part of my cultural nature and training and observation for life. You know, when you spend your life watching people who are what you want to be, you’ll learn a lot more than if you aren’t paying attention. So I learned a lot about being a Latino from being a Latina.

You know, when you spend your life watching people who are what you want to be, you’ll learn a lot more than if you aren’t paying attention.

Vanessa, 51, Atlanta, Georgia, 2016.

I see myself as a born woman. At three years old, I can remember wondering what happened to my vagina and why I didn’t have one. Because I was looking for that. When I was a child, I had dolls, dresses, things from my grandparents in West Virginia. My mother’s mother used to visit from New Jersey and say, “That one should have been a girl. That’s a pretty little boy. It should have been a girl.”

I tried to join the military to get away, to be a man. That didn’t work. When I was in the military, I would go to the base club, and I would get asked to dance by men because they thought I was a black woman with short hair. I always knew that I was Vanessa, that I was a woman, and it had to come out. I joined the military when I was nineteen and did six years. I was a woman on the weekends. I looked forward to getting to my hotel room and being Vanessa. And six years of weekends, you know, it just got old. The reason I didn’t stay in the military was because I had to be Vanessa full-time.

Family has been my worst enemy. Everybody else has embraced me. Even people who didn’t embrace me came along because they got to know me. I have two sisters and five brothers and I’m next to the youngest. I always wanted to be my sister because she was beautiful. I used to sneak into her makeup. My brothers would harass me and say, “You’re a sissy, you’re a girl, you’re a sissy, you’re a girl.” My brother Michael, who passed away, was one of my worst enemies. He was very cruel to me. I mean, we would have physical fights because I wanted to be who I wanted to be, and he just could not deal with it. When I was homeless, people were like, “Well, where’s your family?” They weren’t ready to embrace me like that. So I kept to myself. Even though I was homeless, I tried to keep myself up. I didn’t turn to—and I’m not judging anybody who does—drugs and alcohol and prostitution.

Religion plays a huge part in why the trans community isn’t accepted. A lot of the black churches are still preaching that old-school religion, that what we’re doing is a sin, and God doesn’t approve. They need to get on board. They’re still having problems with the gay marriage thing. I’m telling you by my own experience, I’ve dealt with all the churches. The only ones that did not reach out to me were the black churches.

Before my dad passed away, in 1995, I came home on leave and I told my mom I was gay. You know, back then, everything was identified as gay, even if you were transgender, or transvestite, trans-whatever, you were gay. It was all clumped into one label. So I said, “I’m gay.” And my mom was like, “Oh, well, whatever you do, don’t tell your father.” So I was afraid to tell him. But he knew. My dad died in 1995. That day, his best friend said, “Your father accepted you, and loved you, and knew you was Vanessa.” And I said, “Oh my gosh.” ’Cause I remember he used to call me and say, “So how are you wearing your hair?” And I would say, “Short.” “What does it look like?” That was his way to get me to open up, and I would never do it. I would not tell him. One day he called, and I had just got home from the hair salon. And he asked me about it, and I was like, “How do you know I was at the hair salon?” But I didn’t realize until his funeral that that was his way to try to get me to open up, and for him to say, “It’s OK.”

Daniel, 53, Jacksonville Beach, Florida, 2015.

I identify as a straight male. I’ve always identified as male as far as I can remember. I grew up in a very rural Appalachian setting in the Smoky Mountains in East Tennessee. So, the word “transgender” was not something that I heard growing up. Girls were supposed to act in certain ways. Boys were supposed to act in certain ways. I knew that area was not for me, so I left East Tennessee and became a wild child. I didn’t realize at that time how tough life was really going to be.

I dealt with abuse as a child, a lot of times verbal and physical and sexual abuse. But I didn’t realize until a decade later that the transgender part was really what was causing the turmoil. I always knew that I wasn’t a woman. I just always thought, “Well, something happened somewhere along the line that didn’t click right for me.” Once I was introduced years later to the concept of transgenderism, in the mid-’80s, and the fact that it existed and I was not the only person in the world like that, it was a huge relief. You gotta remember this is still way before the internet. By that time, I had moved back home. I started taking testosterone in East Tennessee, and everyone that knew me there said, “Someone will kill you here.” So I moved to Portland, Oregon, where I officially started my transition. I started hormone replacement therapy in the early 1990s and had my chest surgery a year later. I was so excited the first time I could take my shirt off outside. To me it was a real freedom. I finally felt like I had come into being.

I was so excited the first time I could take my shirt off outside. To me it was a real freedom. I finally felt like I had come into being.

There was a big division in the way I felt like I should be and the way my life had been. It was a very gradual process, but I became a spiritual person and had a deep experience with the Lord, with Jesus. And I became a born-again Christian. I’m an ordained Christian minister. My main focus is on the trans community, but I also do prison ministry. I got the name of one prisoner, this man on death row, and I started writing to him about two years ago. He and I still write, but now I write to thirty-eight people a month. I send them cards and bibles. About half of the people are incarcerated for a long period of time, and most of the trans people are in solitary confinement. I make sure I keep up with the cards and I send one letter, say one three- to four-page letter a month. You know, it doesn’t seem like a lot, but when you’re writing to thirty-eight people a month it adds up. I also have an addiction ministry. More so than a lot of communities, the LGBT community struggles with addiction. It’s very rampant, and there’s a lot of shame for individuals to come forward and say they need help. And the money is not there for many people to get the help they need.

Especially in the trans community, there is such a disconnect from main society. As young people, we are told, “You’re a freak, that’s ungodly what you’re doing, this is wrong, you’re a sinner.” And that’s driven into so many people, including myself, at a young age. That’s not right. There comes a point that each one of us has a reckoning, a very big conversation with God. You will find your peace when you find your peace with God. And there’s many people of different faiths. I’m not telling anyone that one way is better than another to get to that place where you’re at peace with your creator, your higher power, whether you choose to call it God or not. I’m saying get to that place where you can have that conversation and you can be spiritually at peace and then the blessings will start to flow.

Tasha, 65, Birmingham, Alabama, 2013.

I was born in Childersburg, Alabama. When I was growing up, I knew that something about me was different. I knew that I liked the guys. I pretty much today live as a gay man that lives just like a woman, because I see from day one, from that day to this day, I’ve always felt like a woman born in a man’s body. And that’s the way I live. I live as a woman today. I didn’t get to the place of where I’m so all right with this until later in life—at a young age I would’ve had a sex change. But today, I’m so all right with me it doesn’t even cross my mind.

I have never been a case of being in the closet. I’ve always been wide open. And back in that time of the Civil Rights Movement, I still didn’t have any problem. I was still wide open. I participated in the marches and stuff. I was arrested, wet up with the hoses, all that stuff.

Whether you say, “Yes, ma’am,” or “Yes, sir,” I’m all right. I don’t let nothing like that bother me. At times it was kinda rough growing up when you had to hear guys call you all kinda names, such as “freaking fag” and all this kinda stuff. It used to hurt me and make me angry. But as I got into the church and started letting the verse of John 3:16 register in me, a whole lot of stuff changed.

It said, “For God so loved the world that whosoever will, let them come.” And after that, I felt like I was one of the “whosoevers.” And knowing that I was gay and knowing what people were saying, I stopped getting mad. I stopped fighting and [decided to] just be who I am—and just be me. Now, I am real respected in my neighborhood as Tasha because a lot of people don’t even know my real name. I’m Tasha to everybody. And most of the children say, “Miss Tasha.” But when I come upon situations where children are curious and ask, “Are you a man or a lady?” I don’t lie to them. I just tell them I’m a man that lives as a woman. And then I have no problems with them. If you don’t say anything to me, I’m not going to say anything to you, although I have some eyes that can talk to you where I won’t have to say anything. But, all in all, I feel that I done had a good life. I’m just happy with me today, real happy.

Leon, 55, St. Louis, Missouri, 2016.

I was intersex quite by accident. I was going to the doctor to start on a diet and she wanted to run bloodwork. She took bloodwork, then two weeks later she called me and she was like, “Is there something you need to tell me?” And I said, “I don’t think so. What are you talking about?” She said, “There’s just something that I saw in your bloodwork. I need to do more bloodwork.” And I was like, “Oh my God, am I dying?” And she said, “No, you’re not dying, I just want to run a karyotype.” So then, of course, like everybody, you run home, you get on WebMD, and . . . I gave myself so many diseases! So a week later I went back to her, and she said, “We did your bloodwork, and we found out that you are intersex.” And I said, “Bing!” It was like a big lightbulb went off and, from that moment on, everything seemed to fall into place.

At first when I found out, I didn’t want to tell anybody. But I took my good friend with me and on the way home I was like, “I don’t know what to do. What am I gonna tell people?” You know? People don’t understand this. And I’ve never been ashamed of myself. I’ve always done what I wanted to do, when I wanted to do it, and how I wanted to do it, and damn what everybody else thought. But now I was like, “I don’t know what to say.” So when we got back to the office—I worked at Vital Voice at the time—the whole staff asked, “What’s going on? What happened?” So I told them and they were like, “OK.” I said, “So, we’re gonna take this journey together if I decide to do this.” Because I really wasn’t sure. And I was talking to another friend, and he’s like, “Bitch, you’ve gotta talk about this. You’ve got to tell your story, because you have to remember, God or the Universe gave you this for a reason.” So we decided to write an article for the December 2011 issue of Vital Voice, and it took off from there.

I try to talk about intersex and educate people as much as I can and let families know that if your baby’s born intersex, just let it be. Leave it alone. There’s no need to rush off, no need for doctors to lie, because in the past doctors have lied or didn’t even tell the parents sometimes. I just hope that one day society will understand intersex and won’t be so ashamed of it. That’s my mission—to educate. If people ask me questions when I’m out and about, I always answer because I feel like that may be the only time I get to have that teachable moment with them. If they’re brave enough to ask, they’re brave enough to hear what I have to tell them.

I had an older sister, a younger sister, and a younger brother. And I just identified more with my sisters than I did my brother. I just wasn’t a boy. Growing up, I really knew nothing. The only [trans] person I knew was when I took my mother’s Life magazine of Christine Jorgensen and hid it. Later on, I found Renée Richards’s book, Second Serve, and kept it. Those are the only people I knew about.

My mother always told me when I got beat up, “If you weren’t that way, it wouldn’t happen.” I left home two weeks after high school graduation. I was scared of getting drafted into the Army, so I joined the Navy. But I had some bad experiences in the Navy, so I managed to get out early. Then I did everything you’re supposed to do. At twenty-two years old, I got married. I had three kids. I had a career. I was a program administrator. And I just never learned how to be a man. I never took on male socialization skills. And in 1990, I had a massive breakdown. I didn’t know who I was. I hated myself.

So then, over the next twelve years, I was in and out of psychiatric hospitals. I attempted suicide fourteen times. I was in a basement apartment, and I was ready to do it again. Nobody was going to find me that time. But that time, I sat and thought about things. I drove home to California, talked to my sister, and my sister said, “It’s about time.”

Then, my father passed away in ’98 and he had told me before he passed away, he said I had to make some decisions in my life and only when I made them was I going to be happy. You know, it was the first time in my life he said he was proud of me. I just thought he meant I had to get over my depression. But my sister told me that he knew all those years what was the problem. So I came home and I literally left “Mike” in every trash can along Interstate 40. And I came back and started my transition.

Later on, I remember my therapist asking me, “What kind of a woman do you want to be after you transition?” And she made me go home and think about it, and I went back and I said, “I don’t have to think about that. I’ve always been that woman.” It’s only now the outside matches.

“I don’t have to think about that. I’ve always been that woman.”

This essay first appeared in the “Inside/Outside” Issue (Vol. 25, No. 2: Summer 2019).

JESS T. DUGAN is an artist whose work explores issues of gender, sexuality, identity, and community through photographic portraiture. Dugan holds an MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago, a Master of Liberal Arts in Museum Studies from Harvard University, and a BFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Her work is regularly exhibited internationally and is in the permanent collections of several major museums. She is the recipient of a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography, and was selected by the White House as a 2015 Champion of Change. www.jessdugan.com.

VANESSA FABBRE is a social worker and assistant professor at the Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis, where she is also affiliate faculty in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and a faculty scholar at the Institute for Public Health. Fabbre received her AM and PhD in social work from the University of Chicago. Her work explores the conditions under which gender and sexual minorities age well and what this means in the context of heteronormativity, heterosexism, and transphobia.