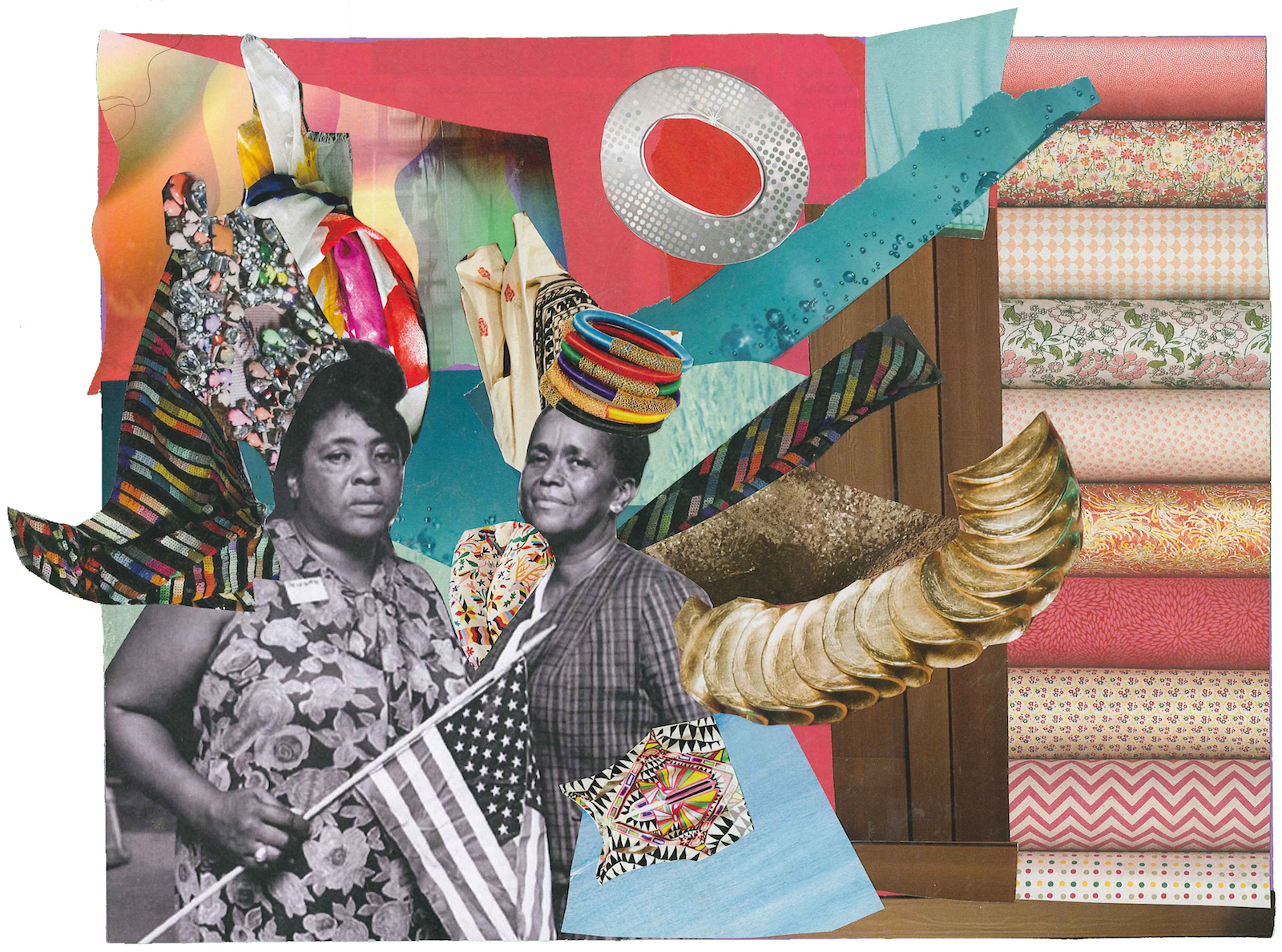

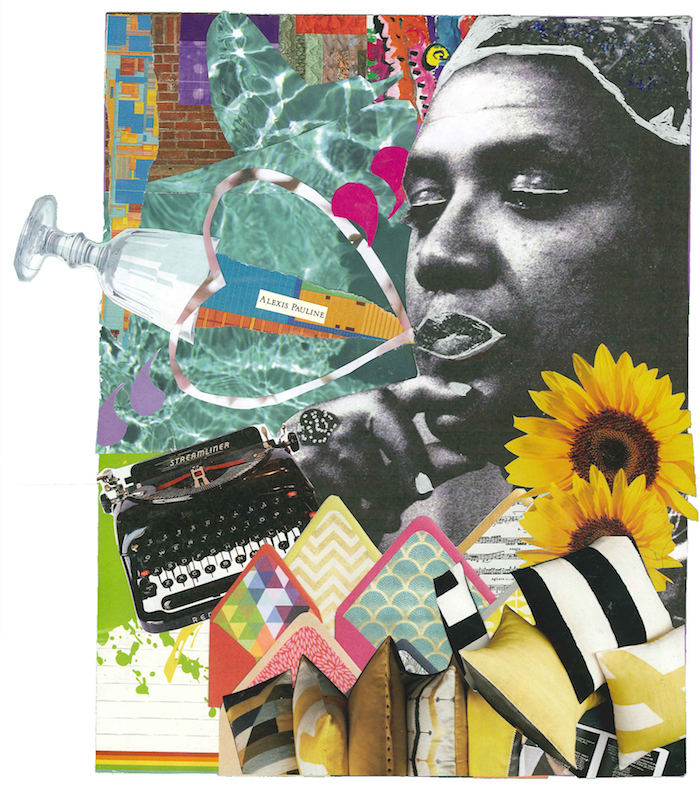

For Fannie Lou Hamer and Audre Lorde.

i.

Go to Tougaloo, the meeting place of two rivers, and be quiet. Wait for the light that floats above the water where Pearl meets Mississippi and step in it. If you are too afraid to trust the light, to know yourself as more than one river, you will never know. Step in when you are ready.1

When you step into the light it is loud, but keep breathing. You will hear what sounds like an ocean of singing, thousands of renditions of “This Little Light of Mine.” Stay still until you know that the light holding you came from within. Let it shine.

This is a portal thousands of years old. Cool from the people who stayed offering centuries of Choctaw care. Smooth from the running of water. Stealth from the breath of the free people who refused to be held by enslavement. It is enough that you are here in this moment. Feel that multitude.

Let your hands lead you to what you want, which is the writing under shore raised like braille so you have to touch it first to know it. Touch that part of yourself that is current and running and flooding at exactly this time. And continue to breathe.

What two rivers agree upon when they meet is the ocean. Their destination. Their longing. That pull. When two rivers meet it is a ceremony, a delegation for only those who have reshaped land with their cleansing. Only those who have learned that the first form of their name is an acrostic of “letting go.” The meeting of two rivers is surrender. It births civilizations and swallows them back. This is why you came to Tougaloo, the meeting point of two rivers, with your question.

ii.

When Afro-Caribbean Black lesbian feminist warrior Audre Lorde came from New York City to be a poet-in-residence at Tougaloo, she had a question about what it meant to be a poet. When she arrived, she was a librarian. By the time she left, she had become a teacher. But those two rivers were all love for the ocean of poetry. A love for rhythm only clarified by the ricochet of bullets from the white supremacists who couldn’t touch the flooding within themselves with bare hands, who were afraid to trust themselves as light, afraid to know themselves as more than one river and who were therefore offended, incensed, moved to violence by the very building, the very greens, the very thought of Black students in college in the state of Mississippi.2

The students wondered something about the poet-in-residence Audre Lorde. “Miss Lorde,” they asked on the first night, “would you call yourself a nature poet?” Because they felt the convergence of rivers and oceans. Because the sound of her voice was reshaping stone. Because they, children of the Delta, could smell the air before the flood. And the flood happened. Audre Lorde let herself love those poetry students so much that she revealed her secrets to them, who she was and who she loved, which is what she taught them to do with their poetry. Be who you are and act on your love. And when the student evaluations came to ask them what they would change they said over and over again that they wanted more. More Ms. Lorde. Could she stay here forever? More. She really inspired and lifted us up. We could be more who we were when she was with us. If we could make a suggestion to the provost, we’d say, “Please let her come back.”3

It was a flood, and also a portal. Audre Lorde fell in love with the students and also with Frances Clayton, a white woman who let herself be known as light and more than one river and part of the ocean of Audre becoming more true to herself. In one sense, it seems like Audre left Tougaloo and returned to New York with new knowing and confidence. But it is also true that she stayed. She stayed committed to Frances whom she would call her sunflower. She stayed in touch with those students whose letters she kept. She was with those same students who were singing in Carnegie Hall, a choir of poets at their own two rivers, a week after her term ended at Tougaloo, when they all got the news that the killers who would not trust themselves as light, would not step into the two rivers, would not admit their salt, had shot down MLK Jr. in Memphis. They were together just then at the meeting of rivers. They were singing full-voice “What the World Needs Now Is Love,” and as they kept on singing with salt on their faces it became more true. As they kept on singing, facing the ocean, breathing the convergence, Audre Lorde was in the portal, writing on the wall.4

iii.

When Civil Rights Movement warrior Fannie Lou Hamer came from Ruleville, Mississippi, to Tougaloo to receive an honorary doctorate during the commencement ceremony, she had a question about sunflowers. About Sunflower County, Mississippi, actually, where she lived and worked. She brought her family to the graduation ceremony and they took proud pictures on the steps of the same library bullet-marked by the guns of the people scared of rivers, where Audre Lorde had met with students the year before. But Fannie Lou Hamer said “bullets or no bullets.” Fannie Lou Hamer was flowering into a flood.5

And since she let herself feel the pain of the mother who had come to her steps after losing her son from such severe malnutrition that his bones never became solid enough to hold up his frame. And since she let herself remember the songs of her mother who said, “I would not be a white man, white as the driven snow, they have not god in their hearts, and to hell they surely must go.” And since she let herself touch the names in the ledger in Charleston that named people as property. And since she put her name on registration rolls for her county even though she knew the bullets were on their way from the guns of the people who wouldn’t float. And since she herself said, “There’s no such thing as I can hate anybody and hope to see God’s face.” And since she had survived assault and beating in the Winona, Mississippi jail. She had a question about how to feed the people of Sunflower County, where the white supremacist-elected official said there were no hungry people.6

This was her postdoctoral project. To honor the flood. To be more than one river at once. And so, though the white supremacists who would not allow themselves to flow were as offended by the idea of Black people eating as they were at the idea of Black people reading, Dr. Fannie Lou Hamer created the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, Mississippi. With donations of all sizes from individuals around the world and organizations like the National Council of Negro Women, she bought fifty pigs and 680 acres of land. They fed 250 families from the first crop. They helped thirty-five families with down payments on homes. They built seventy affordable homes. They granted twenty-five scholarships to students from Sunflower County. They seeded local businesses. They helped families get access to public assistance.7

At the meeting of two rivers, you realize that water is water. It is necessary for life. And though Black residents of Sunflower County were disproportionately excluded from every economic and government opportunity, the domination of white planters also starved white families. Like the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the Freedom Farm Cooperative of one-dollar memberships was inclusive of all residents with shared values and shared needs. What you learn at the meeting of two rivers is that nothing lasts forever and that it also does. The cooperative didn’t last forever but, in 1977, when, in one version of the story, Fannie Lou Hamer died of breast cancer, another story was born that she went on living, as her mentee June Jordan wrote in the New York Times, “one full black lily / luminescent / in a homemade field / of love.”8

iv.

This is how time works at the meeting of two rivers, at the portal of floating light. When Audre Lorde reached, Fannie Lou Hamer was already there, and vice versa, and more importantly they will both be there with many others when you arrive with your question. What will you learn when you reach out your hand wet-faced to read the writing on the wall? That’s for you to know when you get there.

All I can say from here is that you gotta let yourself be a meeting place of rivers. Trust yourself as light. Believe that you can float. And then let go.

This essay first appeared in the Imaginary South issue (vol. 26, no. 4: Winter 2020).

Alexis Pauline Gumbs is author of the forthcoming The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde: Biography as Ceremony. She lives and loves in Durham, North Carolina, and is the cofounder of the Mobile Homecoming Trust.NOTES

- Tougaloo. A Choctaw word meaning “meeting place of two rivers.” In this case, the Pearl River and the Mississippi River, home of the Choctaw for centuries. The place where, as the origin story goes, the staff that had fallen to one side on all other ground finally stood. See “The Floating Light” in Choctaw Tales, collected and annotated by Tom Mould (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004).

- Audre Lorde arrived in 1968 as poet-in-residence.

- Louise Chawla, “Poetry, Nature, and Childhood: An Interview with Audre Lorde,” in Conversations with Audre Lorde, ed. Joan Wylie Hall (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 115. See also James Manigault-Bryant, “Journaling the Body into Nature: Audre Lorde’s Poetic Transgressions of Environment’s Scripture,” Abeng 2, no. 1 (2018): 34–44.

- “Sunflower,” as in a loving metaphorical reference to the actual flower, a real sun-seeking miracle, honoring the Choctaw centrality of sun. Not Sunflower County, where white supremacist farmers tried to starve Black sharecroppers that same year and the several before and after. Audre Lorde, I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde, ed. Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Johnetta B. Cole, and Rudolph P. Byrd (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 121.

- June Jordan, “Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer: In Memoriam,” New York Times, June 3, 1977, 16. Fannie Lou Hamer arrived in 1969 to receive an honorary doctorate at the graduation ceremony.

- Alice Walker, “Can’t Hate Anybody and See God’s Face: Fannie Lou Hamer,” New York Times, April 29, 1973.

- To learn more about Freedom Farm Cooperative and Fannie Lou Hamer, see Chana Kai Lee, For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999).

- Jordan, “Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer,” 16.