Favorite stories from the year.

Clickety-clack. These are the stories our online readers turned to again and again in 2019. Not all of them were originally published this year, but new and old, they continue to resonate. They are poems and stories about finding a voice, as in “The Rime of Nina Simone,” Tiana Clark’s wrenching ode to the singer’s legacy; and “Their Own Talking,” a reflection on the work of civil rights activist Septima Clark. They are conversations that grapple with today’s institutional failures and the urgent need to reinvent them, as in Gene Nichol’s “Losing Carolina” and Kiese Laymon and Tressie McMillan Cottom’s electric dialogue about black excellence and higher education. They are explorations of our impulses to document and memorialize, and our need to work and play and put a good record on.

Thank you for reading with us this year. We’re proud of this creatively rigorous work, and of the diverse and changing South it reveals.

1. The Rime of Nina Simone

by Tiana Clark

2. Their Own Talking: Septima Clark and Women in the Civil Rights Movement

by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Eugene P. Walker, Katherine Mellen Charron, and David P. Cline

Septima Poinsette Clark is a name that should be as familiar to us as Rosa Parks. Both women contributed significantly to the African American freedom struggle, and striking similarities exist in their stories. Each had a long record of participation in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); each challenged segregation and was arrested as a result; and each worked with Martin Luther King. In fact, four months before Rosa Parks’s infamous arrest, she attended a workshop at the Highlander Folk School, an interracial adult education center in Monteagle, Tennessee, where activists gathered to devise solutions for problems in their communities and where Clark served as Director of Education.

Yet, unlike Parks, Clark never captured the national media’s attention for her Civil Rights activism. This certainly offers one explanation for her relative obscurity. Another lies in Clark’s age. Born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina, she was nearly sixty years old when the classic phase of the Civil Rights Movement began, which has eclipsed her role in narratives that focus on youth, such as those in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Finally, there is the nature of Clark’s work in the Movement: using education to empower grassroots people, particularly African American women, so they might become leading citizens in their communities.

“Simply put, their Civil Rights Movement did not ‘end’; rather, it became a way of life.”

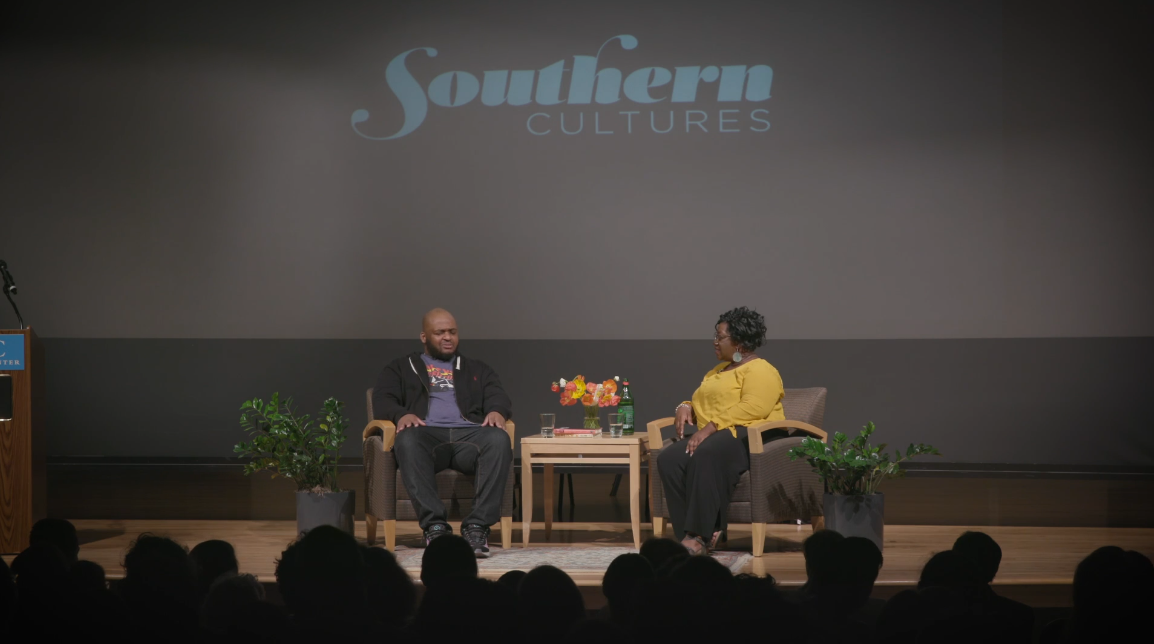

3. Kiese Laymon & Tressie McMillan Cottom in Conversation

from the Backward/Forward Issue Launch

“I just got real personal. I forgot [the audience] was here!”

4. Losing Carolina

by Gene Nichol

It can be an odd undertaking to explore the meaning and mission of an American public university through the lens of history. The concept of a “university of the people”—especially for a southern state university—must begin with a great and unyielding asterisk. Read more >

“It takes generations, or perhaps centuries, to build great institutions. But they can be wounded in a moment.”

5. Signs of Return: Photography as History in the U.S. South

by Grace Hale

“[Parts of the rural South] became de facto open-air museums where poverty, vernacular culture, and a material sense of the past in the present seemed to be permanently on display, even if as time went on you had to crop the Dollar General out of the frame.”

6. Cyclorama: An Atlanta Monument

by Daniel Judt

“If the Cyclorama becomes an artifact for students and historians and ceases to be a monument in which Atlantans invest memory and meaning, it will be . . . one example of how we might retire a monument to the Confederacy, without erasing the history that the monument carries.”

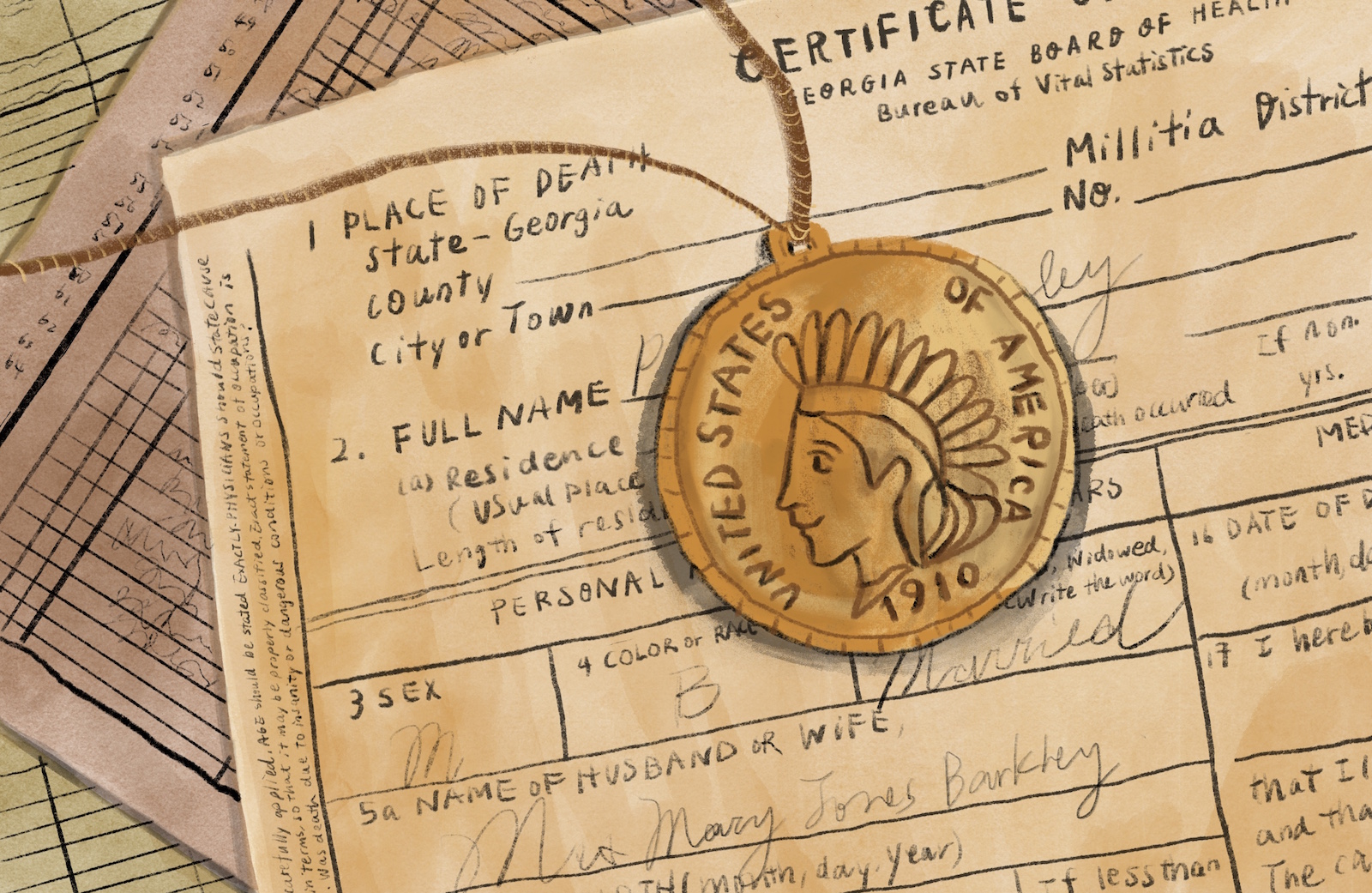

8. Ghosts in My Blood

by Regina Bradley

My great-grandfather was murdered by a white man in 1926, the night before New Year’s Eve. He was thirty-five years old—my grandmother Sara’s father. I call her Nana Boo. She doesn’t have any memories of him because he was killed when she was a baby. His wife, Nana Boo’s mama, Mary Jones Barkley, was the family matriarch who lived well into her nineties. Bluntly put, Ma Mary wasn’t with the shits: she kept her business to herself and expected her family to do the same. When Ma Mary said to do something, you didn’t ask questions. Nana Boo said when Ma Mary started moving furniture around the house, it was time for everybody to go home. Ma Mary worked for herself as a washer woman and a cook, refusing to clean white folks’ houses as a testament to knowing her worth. Before her death, Ma Mary met three new generations of Barkley babies. I was part of that last generation who met her, a girl great-grandchild with the memory of my Daddy sneaking me into her hospital room to see her one last time before she transitioned. Read more >

“I am his great-great-granddaughter. I will tell his story. ’Cause he my people ’nem.”

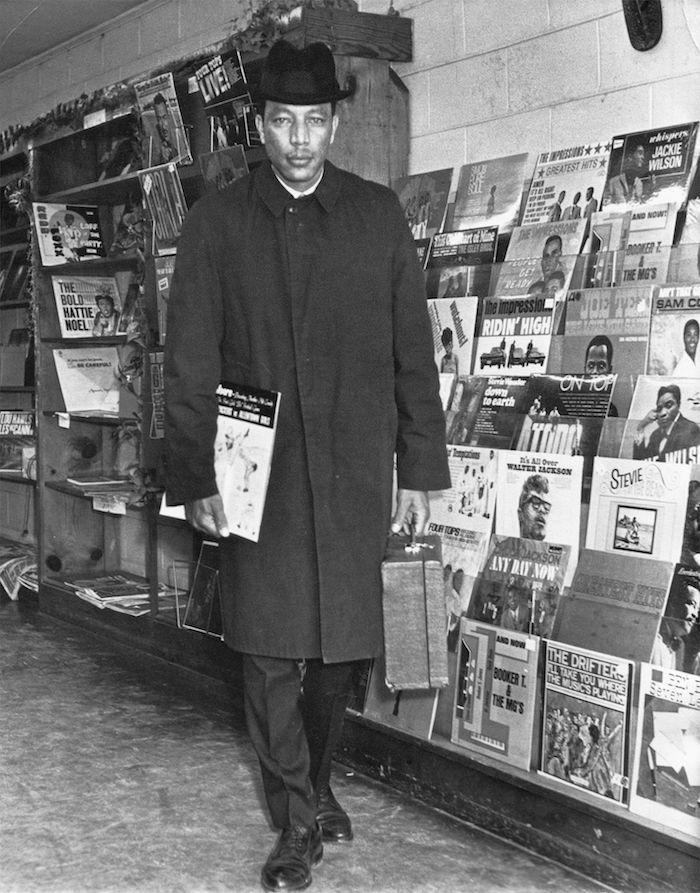

9. For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South

by Joshua Clark Davis

“Records is a market that can be used to brighten the future of lots of black people with jobs and higher prestige all over the country,” Jimmy Liggins announced in 1976 to the readers of the Carolina Times, Durham, North Carolina’s most prominent African American newspaper. Liggins, a minor rhythm and blues star of the 1950s, was publicizing his Duplex National Black Gold Record Pool, headquartered in Durham, which sought to “help and assist black people to own and sell the music and talent blacks produce.” With the aid of this “self helping program,” aspiring hit-makers could record and release music that Black Gold sold through mail order and at Liggins’s shop, Snoopy’s Records, in downtown Durham. Read more >

10. Tasting New Orleans: How the Mardi Gras King Cake Came to Represent the Crescent City

by Anthony J. Stanonis and Rachel Wallace

“‘Sometimes it seems like the entire repertoire of New Orleans cuisine is reduced to king cake and beer during Mardi Gras season.’”