In light of renewed demands for the removal of Confederate monuments from public grounds, we compile a list of Southern Cultures essays about monuments and memorials in the South. These essays examine historical contexts surrounding the crafting and establishment of monuments to the Confederacy as well as to the Civil Rights Era, and they address the power of public commemoration to further preferred social narratives. We have also included essays which explore the development of “grand narratives” about Robert E. Lee, the Confederacy’s top general, and the Civil War more generally, which emphasize white heroism and inform vitriolic responses to alternative perspectives. The deadly violence that erupted in Charlottesvile, Virginia, last August when the city made plans to remove a prominent statue of Robert E. Lee points to deep and unresolved social conflict over the meanings of a shared past. Several essays in this list address constructive responses to racial violence. We selected them to encourage classroom discussion about truth, reconciliation, and the Long Civil Rights Movement.

Finally, we would like to draw readers’ attention to omissions, silences and assumptions when reading Southern Cultures. What authorial biases are apparent? In words or phrases such as “the southern populace” or “southerners” or “Kentuckians” or “Virginians,” are we to default to whiteness when no other distinction is made? If so, what does this tell us about who is present at the southern studies table? And why might this be so?

“Memorial Observances”

Catherine Bishir, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Summer 2009)

What begins as a personal reflection on two Confederate monuments in Bishir’s midst turns out to be a revealing historical narrative, detailing the complex stories about how each statue came to be. Bishir looks first at the statue of a Confederate soldier resting on a high pedestal on the state house lawn in Raleigh, her adopted home. She devotes the second half of the essay to the statue of Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, which stands in downtown Lexington, Kentucky. These histories are particular and general, recounting not just what happened in Raleigh and Lexington, but pointing readers to the ways white supremacists sought to maintain power during Reconstruction more generally and erected the public art to prove it. She writes: “By putting in permanent public form a single version of the past, the creators of these monuments laid lasting claim to their definition of the past and set the terms by which they meant to shape the future” (81). Bishir’s article is a great way to initiate relevant classroom conversations about Confederate monuments in particular and about the role of commemorative art more generally. “We can learn the most from [monuments],” Bishir notes, “By asking not merely what they commemorate but who was doing the commemorating, and when and why” (81).

What begins as a personal reflection on two Confederate monuments in Bishir’s midst turns out to be a revealing historical narrative, detailing the complex stories about how each statue came to be. Bishir looks first at the statue of a Confederate soldier resting on a high pedestal on the state house lawn in Raleigh, her adopted home. She devotes the second half of the essay to the statue of Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, which stands in downtown Lexington, Kentucky. These histories are particular and general, recounting not just what happened in Raleigh and Lexington, but pointing readers to the ways white supremacists sought to maintain power during Reconstruction more generally and erected the public art to prove it. She writes: “By putting in permanent public form a single version of the past, the creators of these monuments laid lasting claim to their definition of the past and set the terms by which they meant to shape the future” (81). Bishir’s article is a great way to initiate relevant classroom conversations about Confederate monuments in particular and about the role of commemorative art more generally. “We can learn the most from [monuments],” Bishir notes, “By asking not merely what they commemorate but who was doing the commemorating, and when and why” (81).

View of the North Carolina state capitol and the Confederate monument, postcard c. 1953. Courtesy the North Carolina Postcard Collection, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Martin Luther King Jr. Streets in the South: A New Landscape of Memory

Derek Alderman, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Fall 2008)

Alderman paints a broad history of resistance and challenges to Civil War-centered commemorations and concepts of the past in the South. By naming streets after Dr. King, African Americans are “rewriting the landscape of southern commemoration” (88). Most students have some experience with streets named after Martin Luther King, Jr. and the controversies surrounding them. This essay is a good discussion piece on the importance of public commemoration and on shared and “preferred” memories. This iteration of Alderman’s research is rich in photographs—it could be read in conjunction with his more analytical piece on the same topic: “Street Fit for a King,” Professional Geographer, 52, no. 4 (2000): 672–684.

Constructing the Cause, Bridging the Divide: Lee’s Tomb at Washington’s College

Christopher R. Lawton, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Summer 2009)

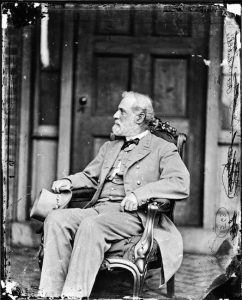

This essay explores the significance of The Recumbant Figure, the funerary statue of Robert E. Lee which stands above his grave under the floor of the chapel at Washington and Lee University. Lawton examines the decision-making process that went into the depiction of Lee in a reclining, sleeping pose. He describes Lee’s actual funeral procession, and the funeral-like procession that followed years later, when the statue of a reclining Lee was carried in a wooden box, strewn with flowers, to the chapel. Lawton writes: “The chapel was…transformed from a place where Lee could worship God to one where the Lost Cause faithful could ‘worship’ Lee” (11). The reclining pose chosen for Lee was not only a fashionable trend in the nineteenth century, but it also harkened back to medieval knights who were depicted in a similar way. Lawton argues that this pose positioned Lee as “the Christian soldier” to a “conquered southern populace” (26). Lawton’s use of period speeches and promotional material surrounding the creation of the sculpture and its installation drives home the powerful rhetoric about Lee’s sense of duty, honor and principle, which has fueled the on-going “grand narrative” about his life (see Carmichael’s “The Truth is Mighty and Will Prevail” from this list).

This essay explores the significance of The Recumbant Figure, the funerary statue of Robert E. Lee which stands above his grave under the floor of the chapel at Washington and Lee University. Lawton examines the decision-making process that went into the depiction of Lee in a reclining, sleeping pose. He describes Lee’s actual funeral procession, and the funeral-like procession that followed years later, when the statue of a reclining Lee was carried in a wooden box, strewn with flowers, to the chapel. Lawton writes: “The chapel was…transformed from a place where Lee could worship God to one where the Lost Cause faithful could ‘worship’ Lee” (11). The reclining pose chosen for Lee was not only a fashionable trend in the nineteenth century, but it also harkened back to medieval knights who were depicted in a similar way. Lawton argues that this pose positioned Lee as “the Christian soldier” to a “conquered southern populace” (26). Lawton’s use of period speeches and promotional material surrounding the creation of the sculpture and its installation drives home the powerful rhetoric about Lee’s sense of duty, honor and principle, which has fueled the on-going “grand narrative” about his life (see Carmichael’s “The Truth is Mighty and Will Prevail” from this list).

Gen. Robert E. Lee, C.S.A., ca. 1863, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Truth is Mighty and Will Eventually Prevail”: Political Correctness, Neo-confederates, and Robert E. Lee

Peter S. Carmichael, Vol. 17, No. 3, (Fall 2011)

On the heels of the Charlottesville riot that erupted in response to the proposed removal of the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee there, Carmichael’s essay about “ways of thinking” about Lee offers useful tools for analyzing discourse about him. Carmichael proposes two underlying schools of thought: Victorian and modernist. Scholars and individuals who adhere to Victorian methodologies prefer a single, grand narrative, which positions Lee as a “grand cavalier”; while modernists propose Lee as complex and flawed, many people at once. With these two discursive practices as illustrations, Carmichael explores the question: Why do debates over Lee become so vitriolic?

On the heels of the Charlottesville riot that erupted in response to the proposed removal of the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee there, Carmichael’s essay about “ways of thinking” about Lee offers useful tools for analyzing discourse about him. Carmichael proposes two underlying schools of thought: Victorian and modernist. Scholars and individuals who adhere to Victorian methodologies prefer a single, grand narrative, which positions Lee as a “grand cavalier”; while modernists propose Lee as complex and flawed, many people at once. With these two discursive practices as illustrations, Carmichael explores the question: Why do debates over Lee become so vitriolic?

Shelby Foote, Memphis, and the Civil War in American Memory

Timothy S. Huebner and Madeleine M. McGrady, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Summer 2009)

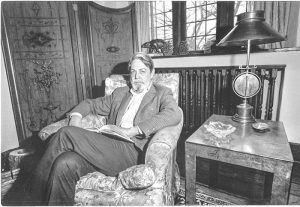

Huebner and McGrady’s profile of southern writer Shelby Foote explores how wide-spread ideas about the Civil War and its white southern heroes get renewed and concretized through popular culture. Ken Burns’s 1991 PBS television series “The American Civil War” relied heavily on Foote’s three-volume The Civil War: A Narrative for inspiration and illustration, and Foote himself appears in the series a total of 89 times. Huebner and McGrady argue that Foote’s perspective as a self-described “novelist-historian” was one that emphasized “honor, heroism, bravery and tragedy in white men fighting and dying” (22). Foote’s Civil War narrative, they maintain, privileges “military conflict over political debate” and “white heroism over black activism” (26). Huebner and McGrady’s retrospective of Foote’s life and work and their analysis of the power of Burns’s platform in contributing to the “popular [white] American memory of the war” are extremely timely in light of renewed debate and conflict over the place of public memorials to the Confederacy. This essay pairs well with Carmichael’s “Truth is Mighty and Will Eventually Prevail” and Lawton’s “Constructing the Cause, Bridging the Divide,” as ways to think about the formation of grand narratives about the Confederate dead.

Huebner and McGrady’s profile of southern writer Shelby Foote explores how wide-spread ideas about the Civil War and its white southern heroes get renewed and concretized through popular culture. Ken Burns’s 1991 PBS television series “The American Civil War” relied heavily on Foote’s three-volume The Civil War: A Narrative for inspiration and illustration, and Foote himself appears in the series a total of 89 times. Huebner and McGrady argue that Foote’s perspective as a self-described “novelist-historian” was one that emphasized “honor, heroism, bravery and tragedy in white men fighting and dying” (22). Foote’s Civil War narrative, they maintain, privileges “military conflict over political debate” and “white heroism over black activism” (26). Huebner and McGrady’s retrospective of Foote’s life and work and their analysis of the power of Burns’s platform in contributing to the “popular [white] American memory of the war” are extremely timely in light of renewed debate and conflict over the place of public memorials to the Confederacy. This essay pairs well with Carmichael’s “Truth is Mighty and Will Eventually Prevail” and Lawton’s “Constructing the Cause, Bridging the Divide,” as ways to think about the formation of grand narratives about the Confederate dead.

Shelby Foote reading in his study, March 2, 1978, by George Walker at Gamma.

Commemorating Wilmington’s Racial Violence of 1898: From Individual to Collective Memory

Melton Alonza McLaurin, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Winter 2000)

McLaurin’s essay tells the back story to the formation of the 1898 Centennial Foundation and the commemorative events planned for the one-hundredth anniversary of the Wilmington race riots. To set up his essay, McLaurin first describes efforts to commemorate nineteenth-century racial violence in two other places: Rosewood, Florida and Tulsa, Oklahoma. It is useful framing for those unfamiliar with these other two Reconstruction-era riots to gain awareness of a pattern of white-led violence against black residents. The Wilmington race riot then emerges as part of this pattern, too, and not as a local event only. McLaurin’s descriptions of the Foundation formation and the commemorative events point to the complex—and often tense—process of grappling with a shared past while having widely differing interpretations of its legacies and meanings. This is a good companion to Bishir’s “Memorial Observances,” as it rings home the specific ways in which whites asserted dominancy just as African Americans were beginning to gain economic and political footholds in the late nineteenth century.

McLaurin’s essay tells the back story to the formation of the 1898 Centennial Foundation and the commemorative events planned for the one-hundredth anniversary of the Wilmington race riots. To set up his essay, McLaurin first describes efforts to commemorate nineteenth-century racial violence in two other places: Rosewood, Florida and Tulsa, Oklahoma. It is useful framing for those unfamiliar with these other two Reconstruction-era riots to gain awareness of a pattern of white-led violence against black residents. The Wilmington race riot then emerges as part of this pattern, too, and not as a local event only. McLaurin’s descriptions of the Foundation formation and the commemorative events point to the complex—and often tense—process of grappling with a shared past while having widely differing interpretations of its legacies and meanings. This is a good companion to Bishir’s “Memorial Observances,” as it rings home the specific ways in which whites asserted dominancy just as African Americans were beginning to gain economic and political footholds in the late nineteenth century.

Truth, Reconciliation, and the Ku Klux Klan

David Cunningham, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Fall 2008)

This essay opens with a discussion of the 2005 trial in which Edgar Ray Killen was found guilty in the 1964 deaths of three Civil Rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Cunningham cautions against this guilty verdict (and others like it) serving as redemption and closure, though, as one such verdict does not implicate the “far-reaching networks of culpability” (70). Two other examples offer alternatives to trial justice for racial violence. First, Cunningham tells the story of Pete Young, a journalist for Raleigh-based WRAL, who was asked to cover a United Klans of America rally in Johnston County, NC in 1964. Young worked with North Carolina Klan members for years after, developing valuable insights sought out by church and government institutions. Cunningham writes, “In contrast with the myriad calls to deal with North Carolina’s growing Klan presence through policing and other legal means, Young relentlessly advanced the idea that the Carolina Klan drew much of its strength from the social and economic isolation and declining sense of opportunity many state residents faced” (72). Young’s program ideas for drawing young rural whites into the mainstream never got off the ground, but they shone light on how working class whites framed their anxieties in “racially divisive ways” (72). Finally, Cunningham describes the Greensboro Massacres of 1979, during which Klansmen killed five anti-Klan demonstrators. A civil trial found white supremacists and the police jointly liable for one of the killings. But it was the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission that pursued restorative justice and created a “structure for those who were harmed to tell their stories and for perpetrators to acknowledge and apologize for their crimes” (78). This is an extremely relevant article for anyone teaching about racial violence. It pairs well with the above article: “Commemorating Wilmington’s Racial Violence of 1898.”

This essay opens with a discussion of the 2005 trial in which Edgar Ray Killen was found guilty in the 1964 deaths of three Civil Rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Cunningham cautions against this guilty verdict (and others like it) serving as redemption and closure, though, as one such verdict does not implicate the “far-reaching networks of culpability” (70). Two other examples offer alternatives to trial justice for racial violence. First, Cunningham tells the story of Pete Young, a journalist for Raleigh-based WRAL, who was asked to cover a United Klans of America rally in Johnston County, NC in 1964. Young worked with North Carolina Klan members for years after, developing valuable insights sought out by church and government institutions. Cunningham writes, “In contrast with the myriad calls to deal with North Carolina’s growing Klan presence through policing and other legal means, Young relentlessly advanced the idea that the Carolina Klan drew much of its strength from the social and economic isolation and declining sense of opportunity many state residents faced” (72). Young’s program ideas for drawing young rural whites into the mainstream never got off the ground, but they shone light on how working class whites framed their anxieties in “racially divisive ways” (72). Finally, Cunningham describes the Greensboro Massacres of 1979, during which Klansmen killed five anti-Klan demonstrators. A civil trial found white supremacists and the police jointly liable for one of the killings. But it was the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission that pursued restorative justice and created a “structure for those who were harmed to tell their stories and for perpetrators to acknowledge and apologize for their crimes” (78). This is an extremely relevant article for anyone teaching about racial violence. It pairs well with the above article: “Commemorating Wilmington’s Racial Violence of 1898.”

Billy Flowers, an Exalted Cyclops of the Johnston County chapter of the UKA, stands in front of his billboard on the outskirts of Smithfield, North Carolina, photographed by Pete Young, courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library.

“The City Too Busy to Care”: The Atlanta Youth Murders and the Southern Past, 1979–81

Paul Mokrzycki Renfro, Vol 21, No. 4 (Winter 2015)

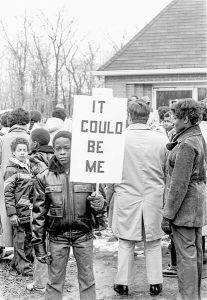

Thirty African American youth were abducted and murdered in Atlanta between 1979–1981. Renfro’s essay examines the historic context surrounding the murders, maintaining that the “Atlanta slayings aggravated long-held black anxieties about racial violence, white hegemony, and the African American future” (43). The black activism that arose in response to the murders drew on lessons from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. This organizing in response to the murders, Renfro argues, should be seen as part of The Long Civil Rights Movement, an on-going freedom struggle in the face of a “regime hostile to freedom struggle” (61). The despair, turmoil and fear experienced by black residents of Atlanta (and elsewhere) during this period are hauntingly familiar today in demands for police accountability in the death of black citizens and for the removal of monuments to white supremacy. These demands, as well as the larger Black Lives Matter Movement, may be seen as further steps in the Long Civil Rights Movement explained and illustrated quite clearly by Renfro.

Thirty African American youth were abducted and murdered in Atlanta between 1979–1981. Renfro’s essay examines the historic context surrounding the murders, maintaining that the “Atlanta slayings aggravated long-held black anxieties about racial violence, white hegemony, and the African American future” (43). The black activism that arose in response to the murders drew on lessons from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. This organizing in response to the murders, Renfro argues, should be seen as part of The Long Civil Rights Movement, an on-going freedom struggle in the face of a “regime hostile to freedom struggle” (61). The despair, turmoil and fear experienced by black residents of Atlanta (and elsewhere) during this period are hauntingly familiar today in demands for police accountability in the death of black citizens and for the removal of monuments to white supremacy. These demands, as well as the larger Black Lives Matter Movement, may be seen as further steps in the Long Civil Rights Movement explained and illustrated quite clearly by Renfro.