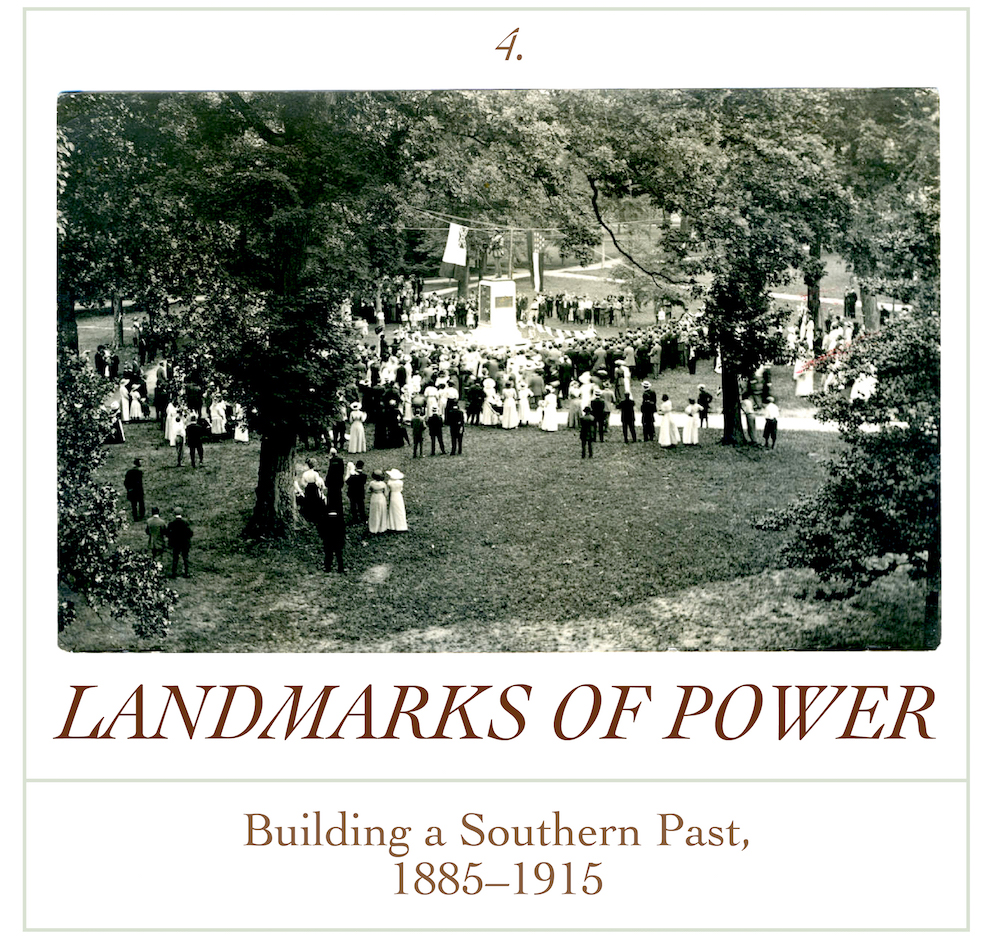

With nearly 25 years of publishing, we frequently share stories from our archives, and, in 2017, many of those found their way to the top (#4 is Catherine Bishir’s essay “Landmarks of Power” from our Inaugural Issue in 1993).

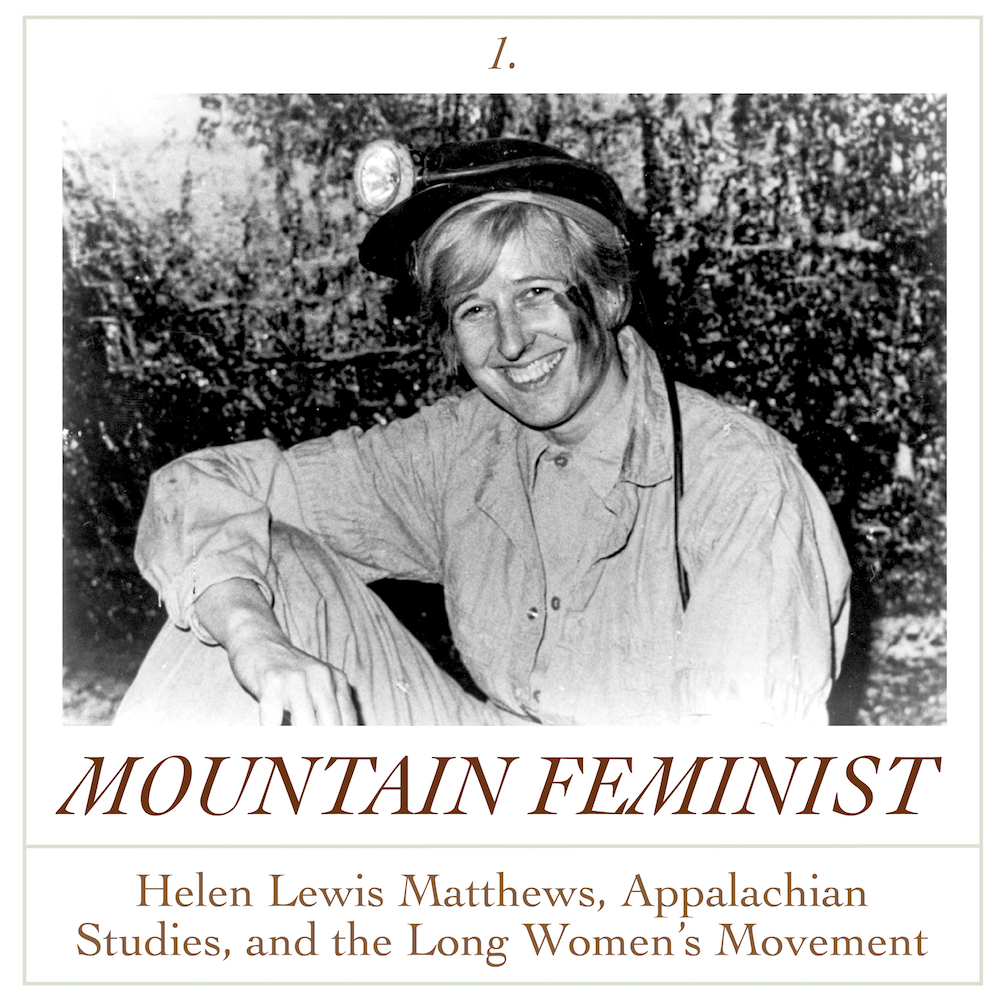

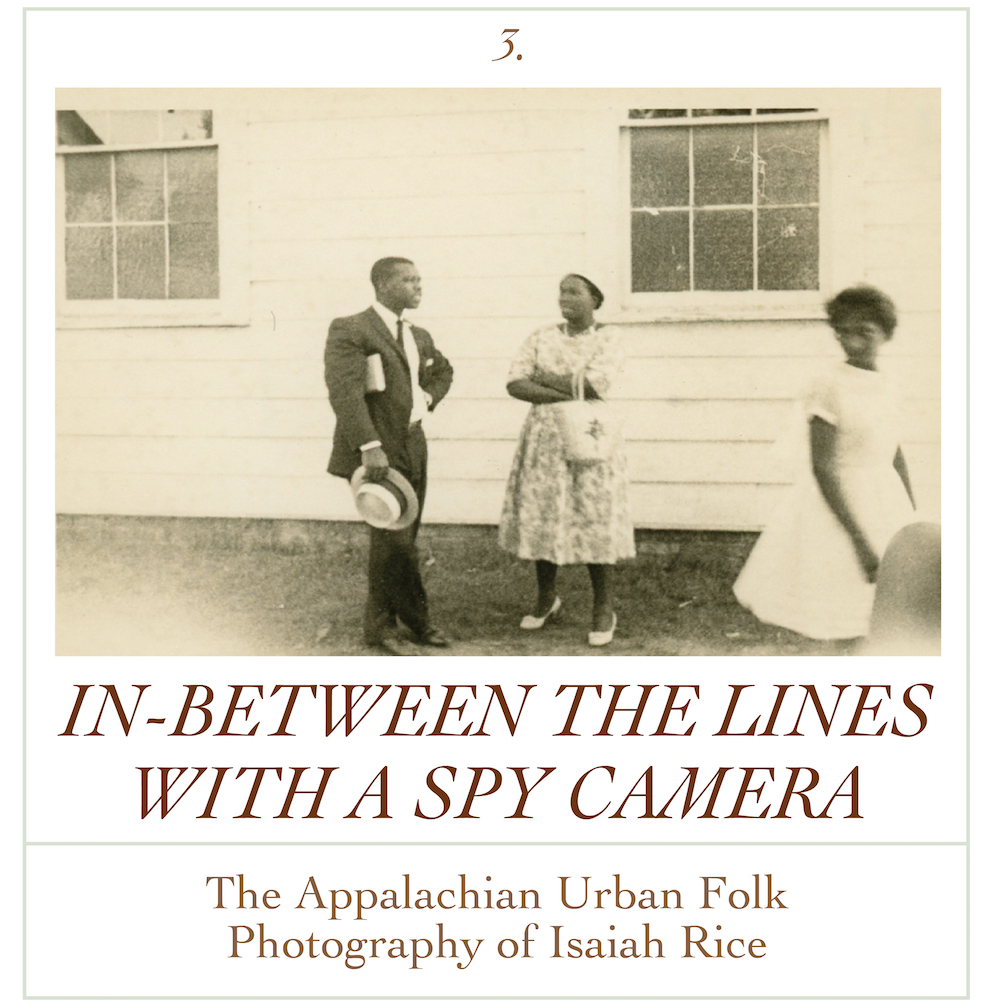

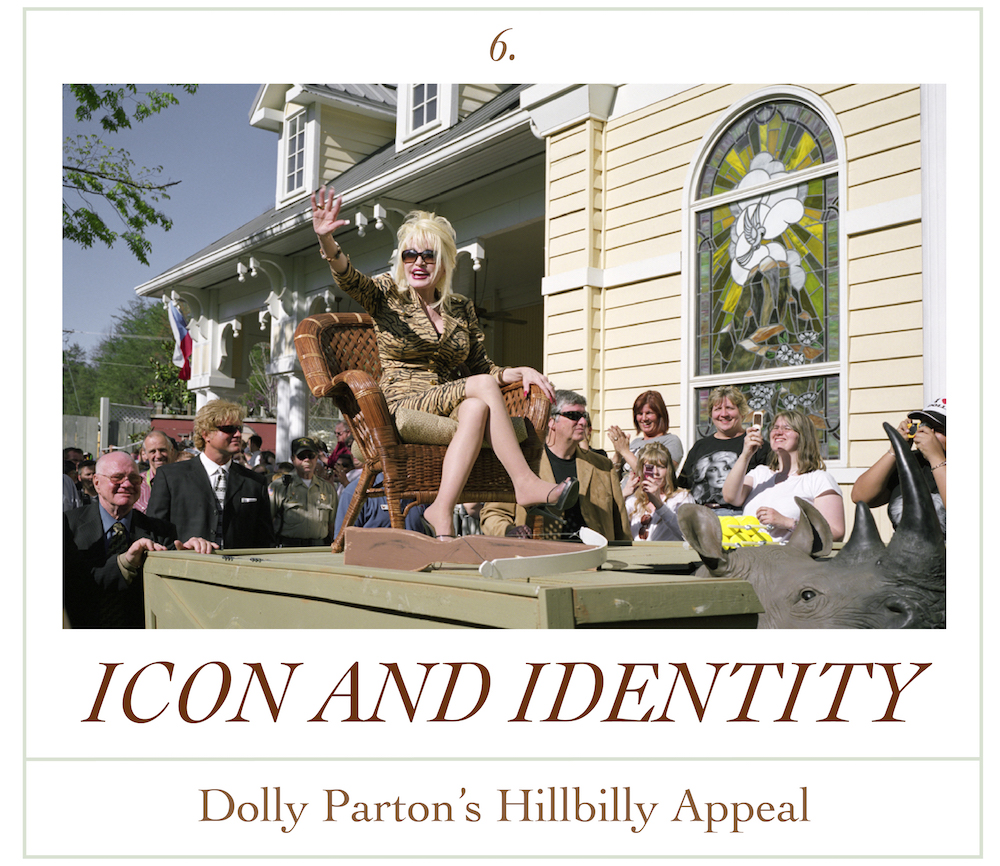

Of course, stories read and re-read tell us something about the times we are living in—and, so often, the times that informed them. As women prepared to march on Washington, D.C., on January 21, 2017, we turned to the work of Helen Matthews Lewis to understand the Long Women’s Movement. On the heels of Hillbilly Elegy and a contentious presidential election, several articles challenge the oversimplified version of Appalachia that’s long been over-served. Contemporary and historic looks at a varied and changing region remind us of the breadth and complexity of these histories and the persistent narrowness of the political narrative. Folklorist Rachel Garringer documents the self-identified “country queers” who proudly remain in Appalachia, Isaiah Rice’s midcentury photographs of his Burton Street neighborhood in Asheville, North Carolina, offer a rare intimate view of black life in the Mountain South, and Graham Hoppe’s essay on Dolly Parton reclaims “hillbilly” as a source of pride.

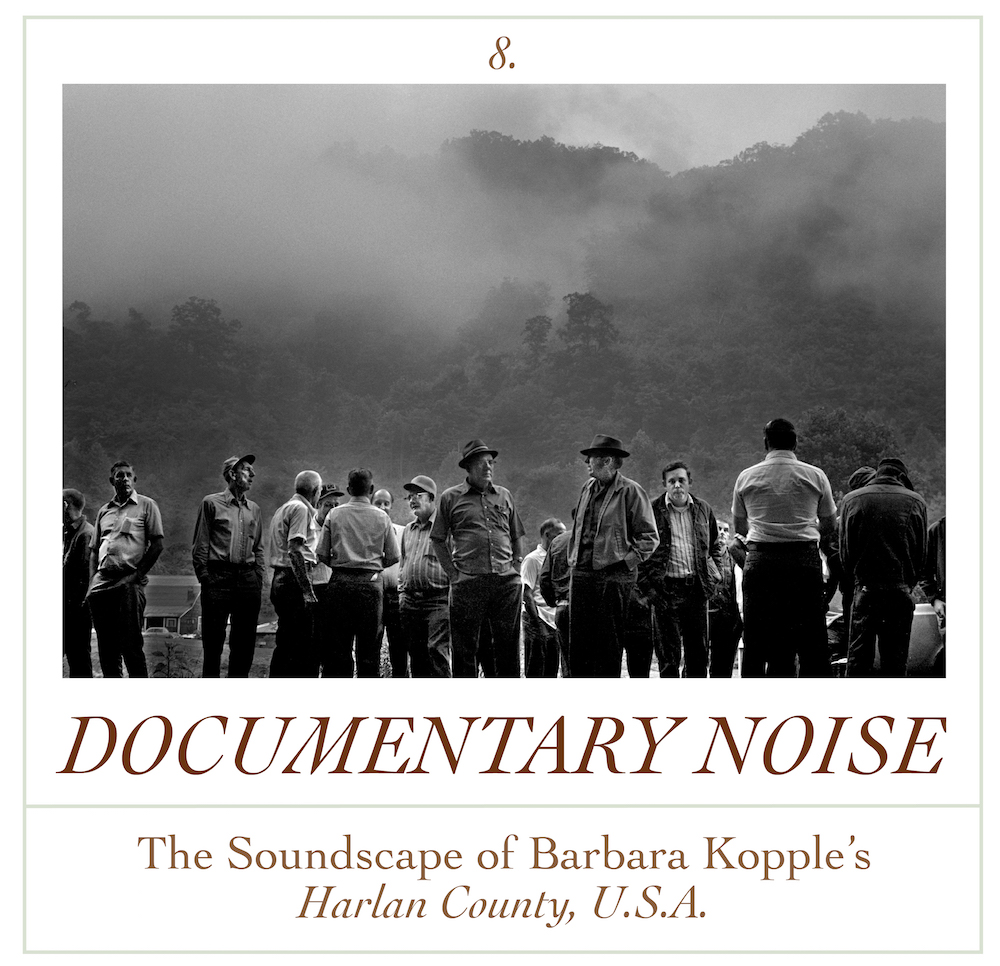

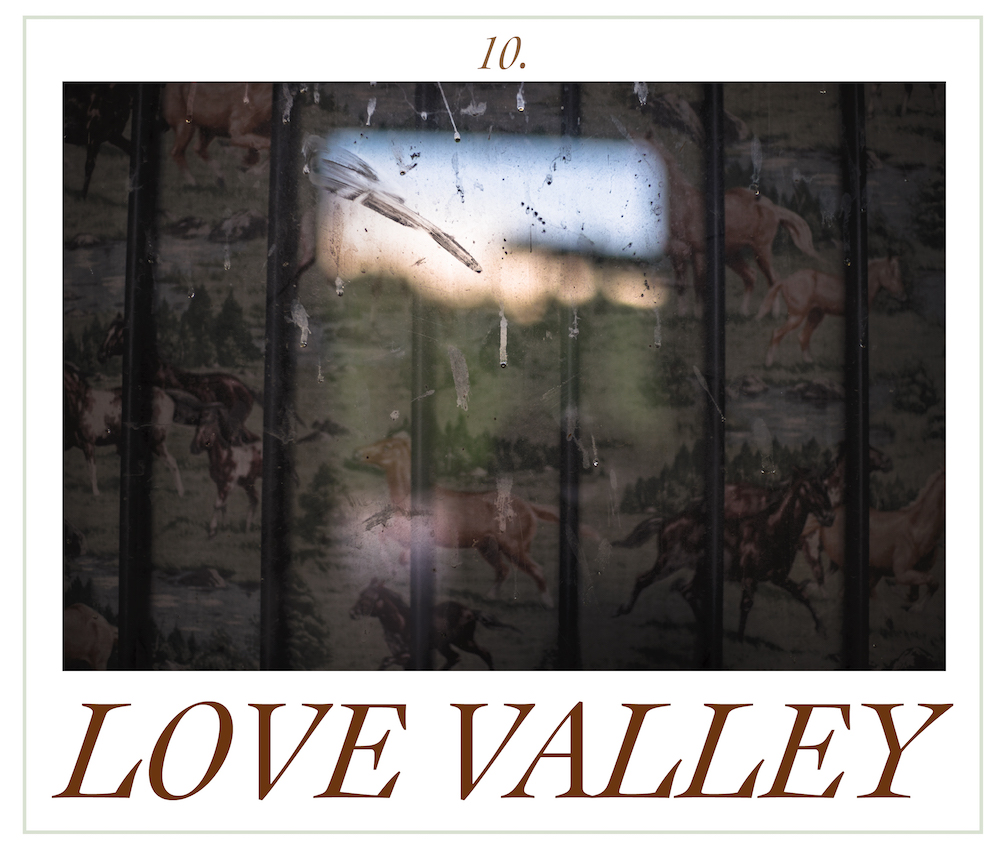

Grace Hale’s essay on Barbara Kopple’s classic film Harlan County, U.S.A. delves into the coal country soundscape to shed new light on the impact of documentary work in Appalachia and beyond. And Michaela O’Brien’s and Tom Rankin’s essays on Love Valley and the Kentucky Derby, respectively, further advance the documentary impulse. O’Brien gives us a personal insight into a world contrived in the imagination that, now, past its heyday, lingers there still, and Rankin takes the long (and close) view of the “First Saturday in May” in a photo essay on his home state’s world-famous sporting event.

Read and re-read, the stories that follow are those that you turned to most in 2017. Thank you for reading.

Compiled and introduced by Jessica Wilkerson and David P. Cline

As women prepared to march on Washington, D.C., on January 21, 2017, Southern Cultures shared an interview from the archives with “Mountain Feminist” Helen Matthews Lewis about her life as an activist. Lewis pioneered the field of Appalachian Studies and has been a social justice and civil rights activist most of her adult life. Here, selected excerpts are presented from an interview conducted with Lewis for the Southern Oral History Program’s Long Women’s Movement in the American South. Her stories of awakening to injustice as a white child growing up in the Jim Crow South, of religious transformation at her discovery of the Protestant Social Gospel, and as a woman barred from the full opportunities and freedoms of a democratic society particularize a life that kept pace with the broad strokes of the Women’s and the Civil Rights Movement. Read here.

There are certain things you have to do. You’re going to get in trouble, but that’s all right. [Highlander’s co-founder] Myles Horton always said, ‘You’re better known by the enemies you make.’

In 2013, folklorist Rachel Garringer created the Country Queers oral history project “out of intense frustration at the lack of rural queer visibility.” Voices in the project speak to a rootedness in Appalachia, countering notions that one must leave to claim their full identity. “For many of us raised in the country, following this normative queer migration narrative rips us from the landscapes, communities, and traditions that are as much a part of ourselves as our queerness,” writes Garringer. “It is my hope that the ongoing Country Queers Project supports other rural queer people in the quest to find a sense of wholeness, a sense of completeness, and a sense of country queer community, in the mountains and beyond.” Read here.

We clung to [Fabulachians] and used it, and used it, and used it, and used it when we first combined it. Because it set something right in ourselves. It announced that we were fully human. That we were whole.

by Darin J. Waters, Gene Hyde, and Kenneth Betsalel

Isaiah Rice was an amateur photographer who documented everyday life in his hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. His photographs offer an insider’s perspective of a vibrant African American community and reveal implicitly the racial segregation that divided (and continues to divide) all southern cities. People attending parades, waitresses in conversation, friends visiting in homes: Rice’s images are often of candid moments that subjects might not be aware are being photographed. These intimate snapshots of Rice’s Burton Street Neighborhood form a picture of a town perhaps at odds with portrayals of Appalachia by mainstream media. Read here.

Documentation of the day-to-day life of Black Appalachians remains far too fleeting, too impressionistic, and too reliant on white sources.

In light of the events in Charlottesville on Saturday, August 12, we shared excerpts from Catherine Bishir’s article in our 1993 inaugural issue. Her essay reminds us that public memory and life are shaped by those in power. Focusing on Reconstruction-era sites and structures in Wilmington and Raleigh, Bishir demonstrates how white elites sought to recover their Civil War losses through classical and colonial revival architectural projects. “By commissioning monumental sculpture that depicted American heroes and American virtues in classical terms and reviving architectural themes from colonial America as well as from classical Roman and Renaissance sources, cultural leaders affirmed the virtues of stability, harmony, and patriotism,” Bishir writes. Read here.

Their memorial work moved beyond commemoration of the Confederacy to mark a continuum of patrician patriotism.

We were not surprised that one of our longtime favorite stories (Go Heels!) was also a reader favorite in 2017: an etymological mystery about the origin of the term “Tar Heel.” College basketball fans are of course familiar with mascots and nicknames, and Tar Heels are among the most proud of our history. The origin of the moniker, its relocation from the Piney Woods to eastern North Carolina, and its transformation from disparagement to pride and from perhaps apocryphal Civil War heroism to a story of race and class in the turpentine trade, are all uncovered here by historian Bruce Baker. Read here.

The most surprising thing about the origins of the phrase ‘Tar Heel’ is that it appears the first person referred to as a Tar Heel was none other than Frederick Douglass.

Just as the nickname “Tar Heel” moved from disparagement to pride, “hillbilly,” too, has been reclaimed, thanks in large part to the good humor, vision, and work ethic of the inimitable Dolly Parton. We’ll let Dolly speak for herself:

“To me that’s not an insult. We were just mountain people. We were really redneck, roughneck, hillbilly people. And I’m proud of it. People always say, ‘Aren’t you insulted when people call you white trash?’ I say, ‘Well, it depends on who’s calling me white trash and how they mean it’ . . . I’m proud of my hillbilly, white trash background. To me that keeps you humble; that keeps you good. And it doesn’t matter how hard you try to outrun it—if that’s who you are, that’s who you are.”

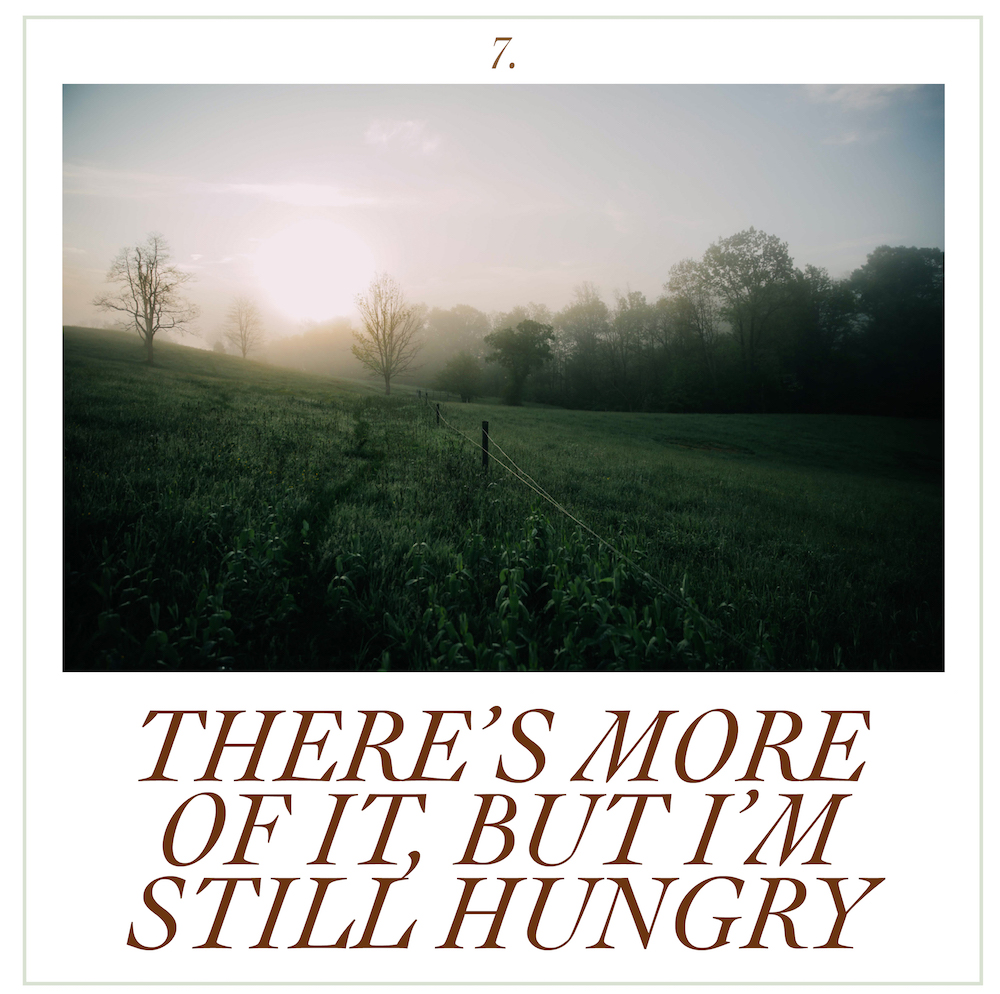

by Courtney Balestier, with photos by Elaine McMillion Sheldon

This text/image “conversation” between writer Courtney Balestier and documentarian Elaine McMillion Sheldon about their native West Virginia is a beautiful rumination on how much place shapes us and how we carry those places—and the idea of them—with us, even as we have to leave to come to terms with them. Read here.

“To be Appalachian often feels, to me, like fighting all the major narrative conflicts at once: man versus nature, man versus man, man versus self. We struggle with the land, our relationship to it and our dependence on it—that dance of resourcefulness and respect, extraction and exploitation. We struggle with the keepers of that land, who are so rarely of us. And we struggle with ourselves, for the damage we cannot seem to help doing, for the difficulty of loving and having reflected at us, in the image of this land that we love, the contradictions that we contain.”

Grace Hale examines the soundscape of Barbara Kopple’s classic film Harlan County, U.S.A., which follows the 1973–1974 strike at the Brookside Mine in Harlan County. “By subtly building a rich soundscape of music as well as other noises, and setting it in tension with the documentary’s cinematography, Kopple both evoked and challenged familiar images of Appalachian poverty,” writes Hale. “In Harlan County, sound works to make the images ‘real’ again, to make them available for alternate meanings.” Read here.

Sound anchors, explains, and makes ‘authentic’ visual imagery compromised by the long history of documentary making in Appalachia.

Intro and photographs by Tom Rankin

“I sent my first Derby bet to Churchill Downs through my parents in 1966,” writes documentary photographer Tom Rankin, “a mere $2 across-the-board wager on Maryland-bred Kauai King.” Since his early bid, Rankin has spent decades capturing intimate views of “greatest two minutes in sports”—the horses, betters, workers, and watchers. Read here.

A nine-year old has never witnessed a sweeter, luckier, and more lucrative victory. Nothing hard about this game, I chortled.

Documentarian Michaela O’Brien discovered the “Cowboy Capital” of Love Valley in the “quirky” section of a list of Things to Do in North Carolina. “I hoped all ninety-eight residents would prove it to me,” she writes. They did. The .2 square mile town entertained with its saloon, sordid history of drugs and rock ‘n’ rollers, and Old West antics. But Love Valley also endeared through many of its people—perhaps its matriarch Ellenora most of all—and the beauty of meandering horse trails in the Piedmont of North Carolina. O’Brien’s “Love Valley” is a story of discovery at almost every turn. Read here.

This is real, not no showplace.